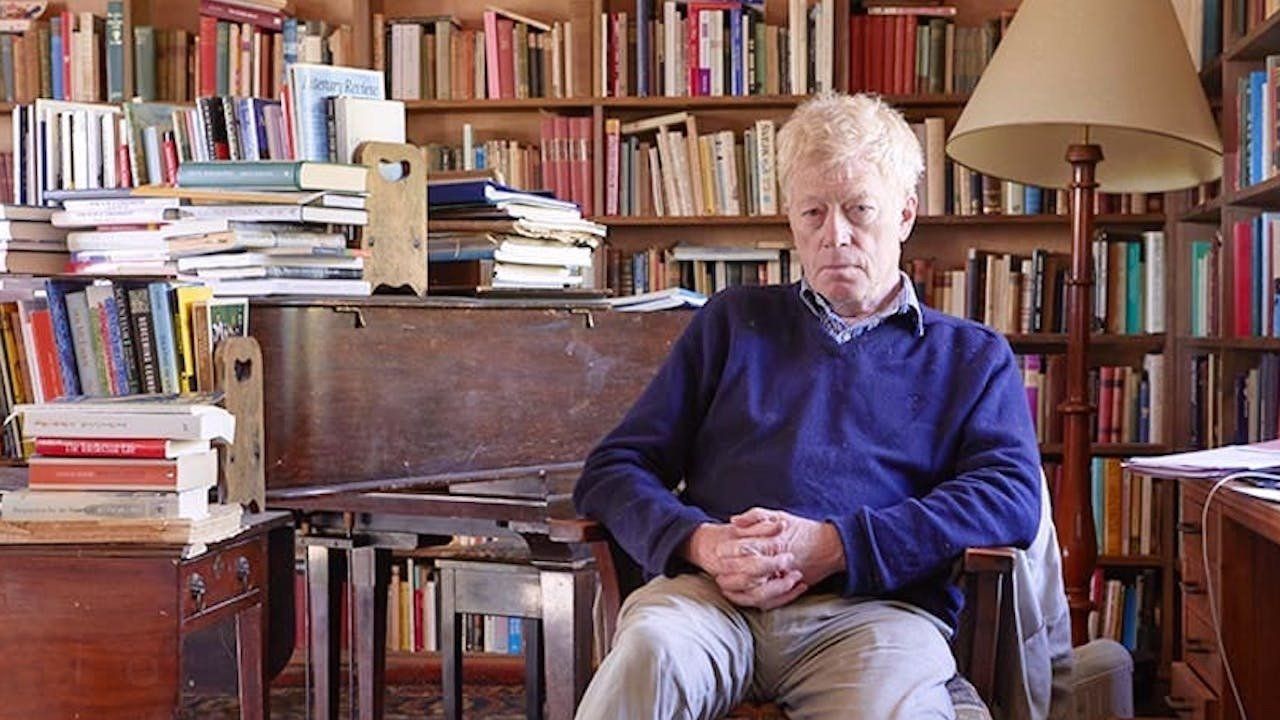

Repentance & Scruton the Reader & Philosopher

by Erin Doom

Feast of St Mary Magdalene, the Myrrh-bearer & Equal to the Apostles

Anno Domini 2020, July 22

“Philosophy” means the love of wisdom. The philosophy taught in British and American universities pays great attention to the analysis of concepts and the structure of logical argument, but seldom issues in anything that looks like wisdom. There are many reasons for this. During the hundred or so years of its existence analytical philosophy has focused on logic, metaphysics and epistemology, with occasional forays into ethics and politics, and has tended to neglect the broader cultural landscape. Topics relevant to the meaning of life—religion, art, music—are often treated dismissively, and the fact that philosophy is literature, to be judged and appreciated as much for its beauty as its truth, has been largely ignored.

Scruton’s interest in philosophy then, is motivated by a love for wisdom that applies to all areas of life, including friendship and wine. And for Scruton, philosophy needs to once again become a “vigilant presence in culture”; it should help us think “clearly about what matters” so that we can more effectively address “the wider concerns of civilization.”

But Scruton doesn’t just say that he believes philosophy should help us answer the question, “How should I live?” He doesn’t merely argue that it should help us make sense of the modern condition. Philosophy is no abstract intellectual exercise for Scruton. Instead, it’s something to put into action, which is exactly what Scruton does. He practices what he preaches. And he’s been doing it for a long time.

My first inkling of this experience came from Bunyan. The year was 1957. I was 13, a day boy at our next-door grammar school, where I learned to distinguish books into two kinds: on the syllabus; and off it. Pilgrim’s Progress must surely have been off the syllabus; nothing else can account for the astonishment with which I turned its pages. I was convalescing from flu, sitting in the garden on a fine spring day. A few yards to my left was our house—a plain whitewashed Edwardian box, part of a ribbon development that stretched along the main road from High Wycombe halfway to Amersham. To the right stood the neo-Georgian Grammar School with its frontage of lawn. Opposite was the ugly new housing estate that spoiled our view. I sat in a nondescript corner of post-war England; nothing could conceivably happen in such surroundings, except the things that happen anywhere: a bus passing, a dog barking, football on the wireless, shepherd’s pie for tea.

And then suddenly I was in a visionary landscape, where even the most ordinary things come dressed in astonishment. In Bunyan’s world words are not barriers or defenses, as they are in suburban England, but messages sent to the heart. They jump into you from the page, as though in answer to a summons. This, surely, is the sign of a great writer, that he speaks to you in your voice, by making his voice your own.

I did not put the book down until I had finished it. And for months afterwards I strode through our suburb side by side with Christian, my inner eye fixed on the Celestial City.

The fact that I am bound by my own desires should provoke weeping and lamentation, shame and disgrace. And yet more terrible is the fact that I bind myself with the shackles that the enemy places upon me, and I slay myself with the passions that give him pleasure. Although I know how dreadful these shackles are, I hide them behind a noble appearance from all who might see. I appear to be robed in the beautiful clothes of reverence, but my soul is entangled with shameful thoughts. Before all who might see, I am reverent, but inside I am filled with all manner of indecency. My conscience accuses me of all this, and I act as if I wish to be freed of my shackles. Every day I worry and sigh over this, yet I ever remain bound by the same snares. How pitiful I am; and how pitiful is my daily repentance, for it has no firm foundation.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.