How I Discovered Books

by Roger Scruton

Feast of St Mary Magdalene, the Holy Myrrh-bearer & Equal to the Apostles

Anno Domini 2020, July 22

Although my father was a teacher, books did not play a large part in our home. Those that could be found in the house were of a useful or improving kind: encyclopedias, the Bible, Palgrave’s Golden Treasury , some gardening books, the Penguin Odyssey , and memoirs of the Second World War. By way of shielding herself from my father’s gloom, my mother dabbled a little in exotic religions, which meant that pamphlets by Indian gurus would from time to time occupy the front room table. But neither she nor my father had any conception of the book , as a hidden door in the scheme of things that opens into another world.

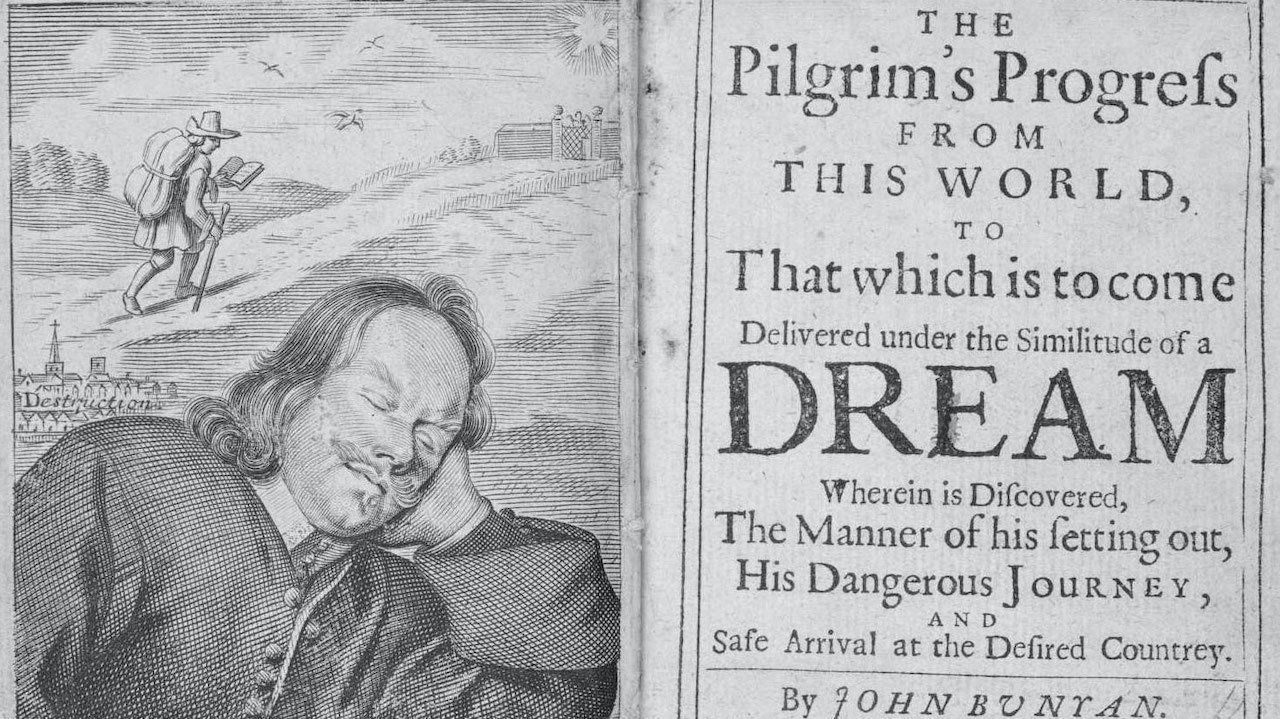

My first inkling of this experience came from Bunyan. The year was 1957. I was 13, a day boy at our next-door grammar school, where I learned to distinguish books into two kinds: on the syllabus; and off it. Pilgrim’s Progress must surely have been off the syllabus; nothing else can account for the astonishment with which I turned its pages. I was convalescing from flu, sitting in the garden on a fine spring day. A few yards to my left was our house—a plain whitewashed Edwardian box, part of a ribbon development that stretched along the main road from High Wycombe halfway to Amersham. To the right stood the neo-Georgian Grammar School with its frontage of lawn. Opposite was the ugly new housing estate that spoiled our view. I sat in a nondescript corner of post-war England; nothing could conceivably happen in such surroundings, except the things that happen anywhere: a bus passing, a dog barking, football on the wireless, shepherd’s pie for tea.

And then suddenly I was in a visionary landscape, where even the most ordinary things come dressed in astonishment. In Bunyan’s world words are not barriers or defenses, as they are in suburban England, but messages sent to the heart. They jump into you from the page, as though in answer to a summons. This, surely, is the sign of a great writer, that he speaks to you in your voice, by making his voice your own.

I did not put the book down until I had finished it. And for months afterwards I strode through our suburb side by side with Christian, my inner eye fixed on the Celestial City.

Two years later, when I was studying A-level science, my parents decided to move. They had found a house in Marlow, smaller, quieter and quainter than Amersham road. The owners—a retired couple called Deas who were emigrating to Canada—drove over to discuss the deal. I was left sitting in the same spot in our garden, drinking tea with their son.

Since Bunyan, few books off the syllabus had passed through my hands. Nevertheless, I had heard rumors of the artistic temperament, and something about Ivor Deas made me suspect that he suffered from the obscure but distinguished ailment. He was a bachelor of some 40 years, still living with his parents. His face was pale and thin, with grey eyes that seemed to fade away when you looked at them. His alabaster hands with their long white fingers; his quiet voice; his spare and careful words; his trousers, rubbed shiny at the knees; and his Adam’s apple shifting up and down like a ping-pong ball in a fountain—all these seemed totally out of place in our suburb and conferred on him an air of suffering fragility that must surely have some literary cause. He sat in silence, waiting for me to speak. I asked him his occupation. He responded with an embarrassed laugh.

“Library,” he said, and I looked at him amazed. To think of it—a real librarian, in our garden, sitting over a cup of tea! What could I say to him? There was an uncomfortable silence as I searched my mind for topics. Mozart was my latest passion, and eventually I asked the librarian if he knew Don Giovanni, from which opera I had just acquired a long-playing record of extracts. He looked at me for a moment, eyes wavering, neck wobbling, hands clutching his knees. Then suddenly he began to speak, quietly, almost tonelessly, as though confessing to some dreadful crime.

“Of course it’s a conundrum, isn’t it—such a perfect work of art, not a note or word out of place, and yet Mozart feels free to add two arias, just like that, because the tenor asks for them! Purists would cut these arias: they hold up the action, destroy the artistic integrity. But music like “Dalla sua pace”—would you remove such a jewel just because—well, I mean, just because it stretches the crown? So to speak.”

Having delivered himself of this weighty utterance he stared down sadly into his teacup, a posture that he maintained in silence until his parents emerged from the house. I was stunned by his words. No track on the treasured LP had stirred me more deeply than “Dalla sua pace,” and the thought that something so beautiful could also be a problem, that a composer might actually think of adding or subtracting it for the sake of the whole, filled me with an astonished sense of the labor, the complexity, the sheer holiness of art. As they were leaving he turned to me and said:

“I hope you enjoy Marlow library. I worked hard on it.”

“And will you still be there? I asked, astonished to have met not only a librarian, but a town librarian.

He gave me a frightened look.

“Oh no. I shall be going with them,” he nodded over his shoulder, “to Canada.”

“Come along, Ivor,” his mother shouted. She was a large, formidable-looking lady, with permed grey hair and layers of woolen clothing in maroon and mauve. With a nod and a gulp the librarian disappeared into the back of the family car, and that was the last I saw of him.

But it was not the last of his influence. In those days immigration from Britain was encouraged by the Canadian government, which subsidized the cost. Mrs. Deas was able to take her furniture and knick-knacks, down to the last Bambi on the mantelpiece. But, as she explained to my mother, Ivor’s books would cause them to go over the weight limit. So would we mind if they were left behind? If we had no use for them they could always be given to the RSPCA.

The first book that I picked from Ivor’s collection was a volume of letters by Rainer Maria Rilke. Needless to say, I had never heard of this writer, but I was attracted by his name. “Rainer” had a faraway, exotic sound to it; “Rilke” suggested knighthood and chivalry. And “Maria” made me think of a being more spiritual than material, who had risen so high above the scheme of things as no longer to possess a sex. I read the book with a feeling of astonishment, just as I had experienced two years before through Bunyan. An air of sanctity, a reckless disregard for the world and its requirements, seemed to radiate from those mysterious pages. Here was a man who wandered outside society, communing with nature and his soul. I did not suspect that Rilke was a shameless sponge; I could not see that these letters, which seem to be all giving, are in fact all taking, the work of a spiritual vampire. To me they exemplified another, higher mode of being, of which I had no precise conception, but for which I tried to find a name: “aesthetic” sounded right at first; but then “ascetic” seemed just as good, and somewhat easier to say. Eventually I used both words interchangeably, satisfied that between them they captured the mysterious vision that had been granted to me, but withheld from those coarser beings—my parents and sisters, for instance—who had no knowledge of books.

Thanks to Rilke, I embarked on the aesthetic, or ascetic, way of life. […]

By now I had discovered Dante, in the Temple Classics edition that Ivor Deas had annotated in a fine italic hand. This was my introduction to symbolism; I formed the conclusion that symbols put us in touch with our real selves, and that our real selves are vastly more interesting than the pretend-selves we adopt for others’ consumption. The theory was confirmed by a reading of Robert Graves’s White Goddess—surely the most dangerous way for a child to discover poetry, but incomparable in its excitement.

Graves challenged me to read more widely. I began to explore Ivor’s other domain, the public library, to whose Eng. Lit. section he had clearly devoted the greater part of his time. All the poets, critics and novelists had found a place in those unvisited rooms, from the windows of which you could see the high wall of a secluded Victorian mansion, occupied, as it happened, by the aging C. K. Scott Moncrieff. It was months before I was to know the significance of that name. But the books that Ivor had collected at public expense, and which I read, usually four at a time, on a table between the bookshelves, were now inextricably fused in my mind with the view of that high brick wall. Wisteria swarmed over the top of it, and a great cedar tree rose in the garden, resting its branches on the coping-stones and hiding the house from view. I read like an alchemist, searching for the spell that would admit me to that secret world, where shadows fall on tonsured lawns, and the aesthetic (or was it ascetic?) way of life occurs in solemn rituals after tea.

Soon order of a kind was established in my literary thinking. Thanks to Mr. Broadbridge, a Leavisite master, those in our sixth form who were doing A-level English came to literature only after being steeped in the vinegar of Revaluation. I too, though studying natural sciences, felt the force of Mr. Broadbridge’s edicts, issued in classrooms three corridors away. Once again, books were divided into those on the syllabus and those off it—the only change being that the syllabus was now indefinitely off the syllabus. Dante was OK, because Eliot said so. But Dante had to be approached through The Sacred Wood, and the going was hard. As for Kafka and Kierkegaard, who had also captured my imagination, they were apologists for sickness, tempters who must be banished by those for whom “life is a necessary word.” The severity of Dr. Leavis appealed to me, since it made my literary excursions into sins. I went on reading Rilke and Kafka, with a renewed sense of being an outsider, obscurely redeemed by the crime that condemned me. And to this day I remain persuaded that it is not life that is the judge of literature, but the other way round.

One of the poets on the Leavisite index was a favorite of Ivor’s. His copy of Shelley, which I still possess, is annotated in every margin. On its title page is Ivor’s name—George Ivor Deas, or Georgius Ivorus Decius as he there expresses it, by way of preface to some lines of Ovid. On the next page, in Ivor’s italic hand, is a sonnet dated 23 February 1945. It captures, in its stilted way, the premonition that all of us feel when the first enthusiasms of youth begin to wane:

Evolution

In youth he shouts to the stars—“There is no God!”

Laughs till Faith withers in his laughter’s flame;

Cries that Law libels Freedom without blame,

That Order sweats and weeps and smells of blood;

Says Life’s a dull game played with smudged old cards;

And Death’s humiliation, no one’s gain;

Envies those lunatics who dare be sane

In handcuffs, elbowed on by bored young guards.

Older, with steel of need and flint of fear,

Strikes God ablaze again through the bare sky;

Drugs with a sleepy Faith Life’s apathy;

Makes hope his soul and Death a doorway near;

Pats Law and Order on their snarling crest,

And lives a meek Assenter with the rest!

The meek assenter who slipped away to Canada at his mother’s command, leaving his life behind, was my savior. Librarians like Ivor made fortresses of books, where taste and scholarship survived and could be obtained free of charge. For those born into bookless homes, but awoken by chance to literature, the public library was a refuge, a place where you could come to terms with your isolation. It was made so by people like Ivor.

I recently had cause to remember him. I had been looking for Wagner’s writings from Paris—a collection of wonderful essays and stories, the kind of book every library should possess, if only to offer a true record of our culture [Wagner writes from Paris: Stories, essays, and articles by the young composer (J. Day Co., 1973)]. On the title page, at the very place where George Ivor Deas would have copied out his name, is a red stamp: “Discarded by the Hackney Library Services.”

*Excerpted from chapter 1 in Roger Scruton, Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life (New York: Continuum, 2005), 1-6. Available for purchase from Eighth Day Books. Learn more about Sir Roger Scruton here at his website.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.