St Patrick the Monk

Byzantine Influence on Celtic Monasticism

by Erin Doom

Feast of St Gerasimus the Righteous of JordanAnno Domini 2020, March 4

“The widespread and vibrant monasticism manifest in the Celtic lands of the sixth century could not have existed unless the groundwork for it had already been laid” (15).

“…in order to determine more exactly the relationship between Oriental and Celtic monasticism, we will have to explore in greater detail the circumstances and rules guiding daily monastic life in Hibernia” (37).

Gregory Telepneff, The Egyptian Desert in the Irish Bogs: The Byzantine Character of Early Celtic Monasticism (Etna, CA: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 2001).

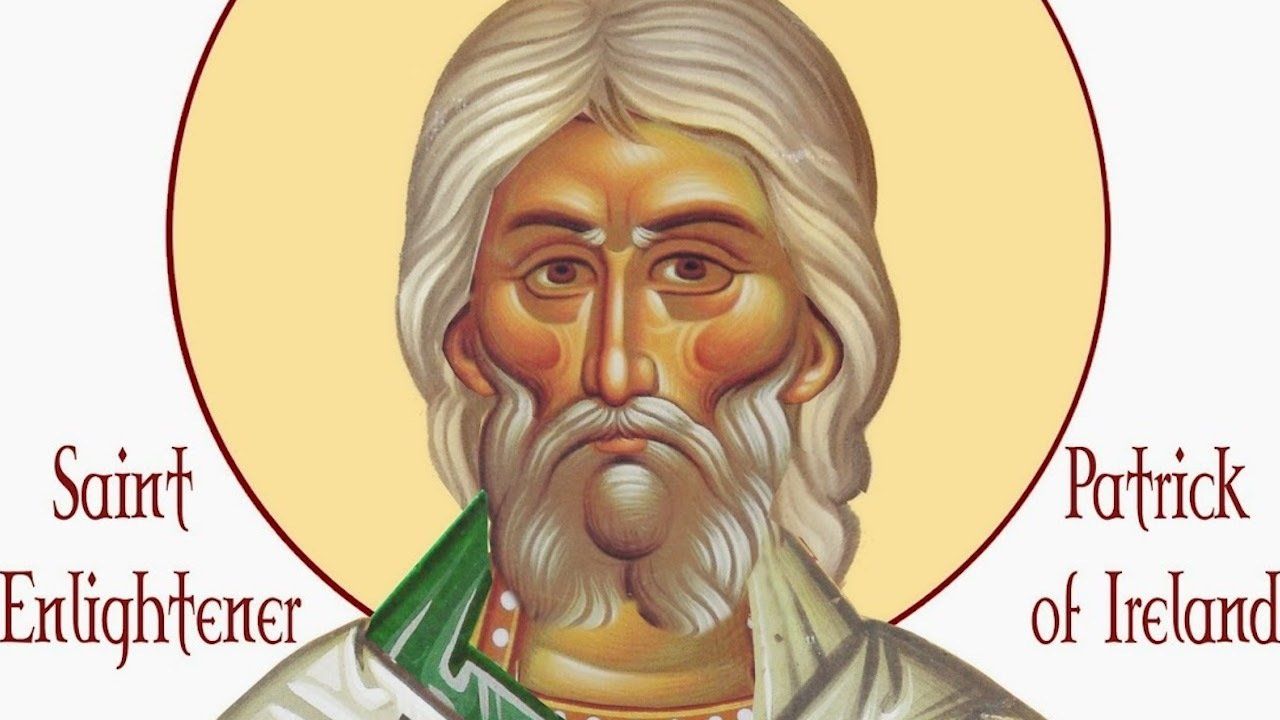

In most people’s minds, the mention of Celtic Christianity typically conjures up an image of St. Patrick. Few associate him with Celtic monasticism. However, as Gregory Telepneff makes clear in his fascinating little book, The Egyptian Desert in the Irish Bogs , if one actually reads the works of St. Patrick, monastic references are found all over the place. “Consecrated virgins” are mentioned on several occasions in his Confession. In his Canons, St. Patrick refers to the vows taken by these virgins. In his Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus, St Patrick writes about the numerous sons and daughters of kings who “were monks and virgins in Christ.” And there are more references to monks and virgins in his Fragments. Moreover, Telepneff observes that an even more interesting monastic reference can be found in the Canons where St. Patrick restricted the wandering monastics without the permission of the superior, a rule that can also be found in the writings of St. Pachomius, as well as other Byzantine literature. And yet, in spite of all this textual evidence, Telepneff concludes that the monastic element has regrettably been “flatly ignored” by many who write on Celtic Christianity.

St. Patrick’s writings also reveal ascetical characteristics similar to those of Byzantine monasticism. St. Patrick refers to, for example, rising before dawn to pray, numerous set times for daily prayer, fasting, embracing poverty, and longing for poverty. Celtic monasticism also tends more toward a "strict ascetic life of anchoritism" than Western forms. Pilgrimages and voluntary exile are also typical of Celtic monasticism, which are common in Byzantine monastic literature (e.g. the third rung of St. John of Climacus’ Ladder of Divine Ascent is titled “On Exile or Pilgrimage” and St. Gregory of Nyssa penned a work titled On Pilgrimages ).

Telepneff provides further evidence for the relationship between Byzantine and Celtic monasticism by turning to similarities between the monastic writings of the two forms. There are many similarities between The Life of St. Columba and The Life of St. Anthony: both monks receive the gift of prophecy; both observed souls ascending to Heaven or descending to Hell; both received the gift of spiritual discernment; and the authors of both works (St. Adamnan of Iona and St. Athanasius) stress the grace of God as the source of their miracles and prophecies.

Telepneff also notes the similarities between The Rule of St. Columbanus and the writings of St. Pachomius, St. Cassian, and the Sayings of the Desert Fathers. A few immediate examples include: obedience as the foundation of the coenobitic life, an emphasis on silence, and food intake limited either to the Ninth Hour (3:00 P.M.) or to the evening. Telepneff next turns to the Regula Coenobialis of St. Columbanus in which sins of word, deed, and thought are commanded to be confessed. The confession of thoughts is of particular importance, for this was dealt with extensively by St. Cassian, who received the teaching from Evagrius Ponticus. In fact, a third document by St. Columbanus, the Penitential, stresses the vital role thoughts play in the Christian life. In this text, St. Columbanus argues that vices are to be dealt with by their opposites (e.g., gluttony with fasting, anger with silence, et. al.), an idea borrowed from Cassian, who received it from Evagrius. This focus on thoughts is further explored by St. Cuimmine Fota who, once again borrowing from Cassian and Evagrius, wrote a treatise on the eight vices.

In addition to common ascetical practices and common literary traditions, Telepneff also points to the “unusual circumstances of monastic life” common to both Celtic and Byzantine monasticism as “one of the most convincing arguments for direct Coptic influence on Celtic monasteries.” For example, the ascetic practice of praying all night with the arms outstretched in the form of a cross is found in both the Life of St. Kieran of Clonmacnoise and the Life of St. Pachomius. Or, for a more extreme example, which is common only to Byzantine and Celtic monastic texts, monks would stand in cold water for an all-night vigil.

Finally, Telepneff argues that Celtic monasticism would have actually encountered Byzantine monks. We are aware of at least one reference to the presence of Byzantine (Coptic and Armenian) monks in Ireland. Additionally, there is evidence of Celtic pilgrims visiting the Holy City, of whom Telepneff argues that we can be certain that some of them were monastics. Furthermore, there is evidence of Celtic travel guides who led groups to visit the Nitria and Sketis monasteries in Egypt. The problem is that these are isolated references and there is thus no widespread evidence. However, Telepneff goes on to note two illustrations in which monastic writings (Egyptian, Greek, and Syrian) alone have been sufficient influence to provoke monastic revivals. Through the rediscovery of lost patristic texts on Mt. Athos, the Russian monk St. Paisius Velichkovsky spearheaded a great monastic renewal in Moldavia, Romania, Russia, and the Ukraine. Similarly, St. Nicodemus the Hagiorite used the same patristic texts to spark a great revival in Greece. Telepneff does admit that there is a significant difference here since these two figures sparked renewal in a pre-existing monastic milieu, whereas the monasticism in Ireland was in the process of being formed. Nevertheless, the power of the influence of literature cannot be denied and must be considered when examining the development of Celtic monasticism.

With explicit references to monasticism in St. Patrick’s writings, ascetical practices that are common to both Byzantine and Celtic monasticism, the direct presence of Byzantine monks in Ireland, the interaction between East and West through Celtic pilgrims and travel guides, and the circulation of Byzantine monastic texts in Ireland, the argument for a Byzantine connection to Celtic monasticism has a solid foundation that can only continue to be built upon.

Erin Doom is the founder and director of Eighth Day Institute. He lives in Wichita, KS with his wife Christiane and their four children, Caleb Michael, Hannah Elizabeth, Elijah Blaise, and Esther Ruth.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.