St Irenaeus and The Da Vinci Code

by Erin Doom

Feast of St Hilary the Wonderworker

Anno Domini 2022, May 4

Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code, released in April 2003, was an immediate success, debuting in the number one spot on the New York Times best-seller list and remaining number one or two for the vast majority of sixty weeks. It has been so popular and publicized that it now has over 70 million copies in print and is being translated into over forty languages. Why such a stir over a novel?

The surface plot of Brown’s book is a bit shocking when compared with the traditional understanding of the Biblical Jesus. The novel portrays Jesus and Mary Magdalene as married with children, Mary Magdalene as the chief apostle instead of Peter, the Catholic Church as an oppressive institution that has suppressed these facts for 2000 years, and Jesus as a good man who was deified by Constantine in 325 A.D. While this spin may cause a huge shock factor and thus create a Harry Potteresque publishing phenomenon, there is more to the story than meets the eye.

Another explanation for Brown’s success may be found beneath the surface of the plot in its pervading gnostic message. While the book is written as a novel, Brown clearly has a point he is trying to communicate and one that, according to him, is researched and based on fact (fn 1: see www.danbrown.com/novels/davinci_code/faqs.html. The novel also has a disclaimer page titled “Fact” where Brown claims that “All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate.”). This “researched,” “factual” and “accurate” message is presented as a secret and special knowledge (gnosis: Greek for knowledge) that has been hidden from the public and is only now being made available to those willing to accept an alternate account of history. However, there is nothing new, exciting or secret about Brown’s message, as most readers believe it to be. In fact, many of his ideas date back to an ancient system of religious thought known as Gnosticism.

Gnosticism, while difficult to precisely define (fn 2: Harvard professor Karen King explains the difficulties and complexities of defining Gnosticism: “The problem, I argue, is that a rhetorical term has been confused with a historical entity. There was and is no such thing as Gnosticism, if we mean by that some kind of ancient religious entity with a single origin and a distinct set of characteristics. Gnosticism is, rather, a term invented in the early modern period to aid in defining the boundaries of normative Christianity. Yet it has mistakenly come to be thought of as a distinctive Christian heresy or even as a religion in its own right.” What is Gnosticism?, Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2003, p. 2. See also Michael Allen Williams, Rethinking “Gnosticism”: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category, Princeton Univ. Press, 1996), according to James A. Herrick in The Making of the New Spirituality,

manifests itself in the veneration of secret spiritual knowledge, the elevation of spiritual elites in possession of such knowledge, a denigration of time and history, a tendency to view the physical realm as evil and a corresponding tendency to view human embodiment with suspicion…In its most elemental form, gnosticism is the systematic spiritual effort to escape the confines of history and physical embodiment through secret knowledge (gnosis) and technique (magic)…Thus, Henri-Charles Puech has called Gnosticism “a ‘revolt’ against all myths and belief systems which purport to give time some indwelling meaning (pp. 178-179).

As a result, any “myth” or “belief system” that honors time and history, or allows the physical nature of humanity and the earth to have any real significance, is an enemy of Gnosticism. Thus, traditional Christianity and its historical message of a beginning and end of time, as well as its positive emphasis upon the physical world (fn 3: In the creation story of Genesis, upon completion God looks upon the fruit of his labors and says it is very good (Gen. 1:31). Additionally, Christianity holds the doctrine of the incarnation of Christ as a fundamental and essential tenet to their faith, thus giving an even greater role to the physical body.), has been one of gnosticism’s greatest enemies for nearly 2000 years.

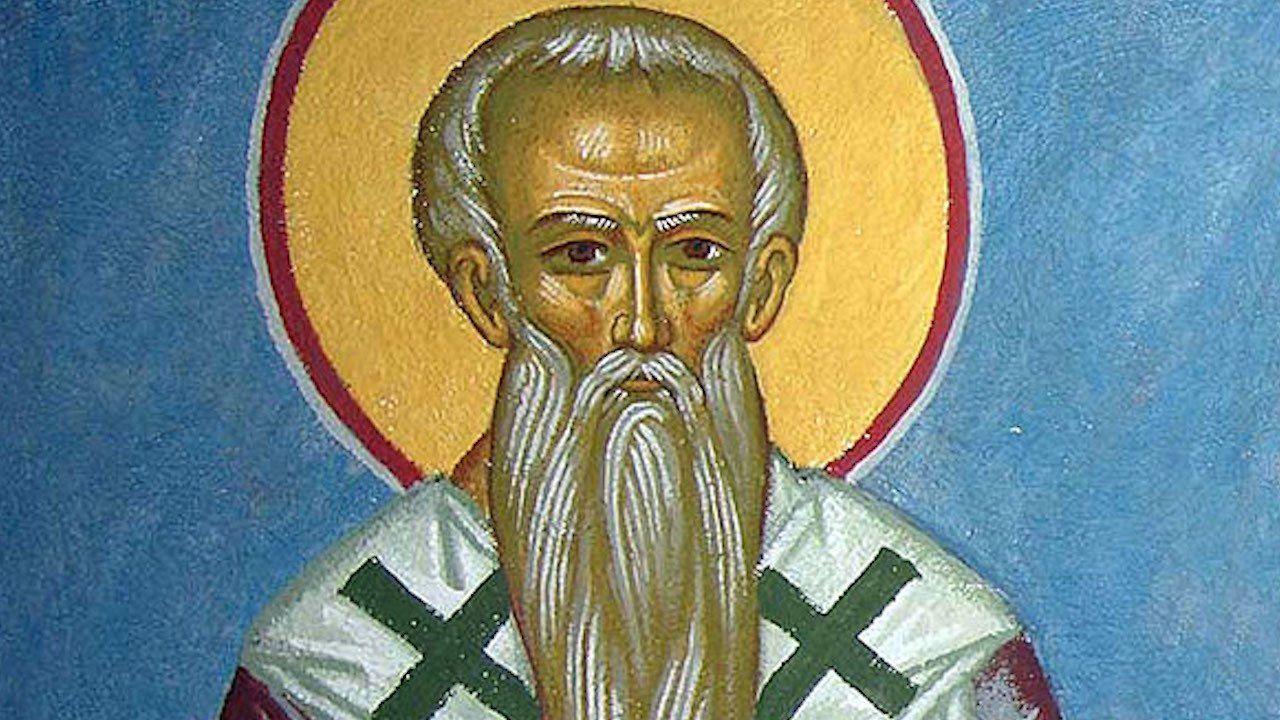

The clash between Christianity and Gnosticism dates back to the very beginnings of the Christian Church. There are hints of the initial stages of this controversy in the first epistle of John (fn 4: 1 John 1:1, 4:2: “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands…By this you know the Spirit of God: every spirit which confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is of God”), written sometime toward the end of the first century A.D. However, the controversy really came to the fore in the second century when the bishop of Lyons, armed with ink and parchment, set out to expose and refute the expanding influence of Gnostic teachings.

Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons, is considered by many to be the first systematic theologian and thus the most important Christian personality between the apostles and the towering third century Alexandrian genius named Origen. Sometime between 175 and 189 A.D., Irenaeus penned five books against the Gnostics, collectively titled On the Detection and Refutation of Knowledge Falsely So Called and more commonly known as Against Heresies. In the first book, Irenaeus sets out “[i]n the manner of a surgeon performing a major operation…to lay bare the nerves and sinews and so take us to the very heart of the Gnostic heresy,” (fn 5: H.B. Timothy, The Early Christian Apologists and Greek Philosophy Exemplified by Irenaeus, Tertullian and Clement of Alexandria, Van Gorcum & Comp. B.V., 1973, p. 23), meticulously describing the errors of the Valentinian Gnostics and their predecessors. Using logic and rational proofs, Irenaeus continues his operation in book two as he attempts to demonstrate the absurdity and falsity of Gnostic doctrines. Pressing on in books three and four, Irenaeus turns to the words of Jesus’ apostles in the third book and then to the sayings and parables of Jesus in the fourth book for proofs against Gnosticism. Finally, wrapping his operation up in the fifth book, Irenaeus zooms in to the heart of the matter by arguing for the salvation and resurrection of the body, thus implying the goodness of matter, a point sharply denied by the Gnostics. Viewed as one massive masterpiece, according to the historian Robert Grant, Irenaeus

built up a body of Christian theology that resembled a French Gothic cathedral, strongly supported by columns of biblical faith and tradition, illuminated by vast expanses of exegetical and logical argument, and upheld by flying buttresses of rhetorical and philosophical considerations from the outside (fn 6: Irenaeus of Lyons, Routledge, 1997, p. 1),

resulting in a treatise that proved to be very popular among anti-gnostic Christians.

Despite its popularity, Irenaeus’ original Greek text was mysteriously lost and never recovered, posing a common but serious problem for ancient historians. The Greek text appears to have been available in the sixth century to translators of an Armenian version, in the eighth century evidenced by excerpts in John of Damascus’ text Sacra Parallela, and even up until the ninth century when Photius read a copy at Baghdad—it has been suggested that this copy was possibly lost when Baghdad was sacked in 1258 (fn 7: Dominic J. Unger, St. Irenaeus of Lyons Against the Heresies Vol. 1 Book 1, Mahwah, NJ: 1992, p. 12).

When an ancient text is lost or destroyed, such as this treatise, the next step is to locate other sources that may have portions of the original text copied. What we do have today of Irenaeus’ original Greek text comes from various writers who quoted extended Irenaean passages in their own works. Most of book one is available, thanks to Epiphanius, who makes it clear when he is copying verbatim and when he is merely summarizing. We also have a number of sections in two other treatises on heresies, one by Hippolytus and the other by Theodoret of Cyrus. Eusebius also preserves portions of Irenaeus’ original text, plus a bonus of two Irenaean letters! Additionally, there are several passages preserved in St. John of Damascus’ Sacra Parallela and Catenae, as well as fragments in the Oxyrhynchus papyrus 405 (fn 8: This is the oldest fragment of the text, dated to the end of the second century and originating from Egypt.) and Jena papyrus (fn 9: Unger, p. 11). As to the remaining portions of the text, which are quite considerable, we are dependent upon the next best source of lost texts: later preserved translations.

There are nine surviving manusripts of Irenaeus’ work, all Latin translations dating from the ninth to the sixteenth centuries (fn 10: Clermont manuscript, ninth century; Voss manuscript, 1494; Holmiensis A 140 manuscript, end of fifteenth century; Arundel manuscript, 1166; Vatican manuscript Latin 187, 1429; Vatican manuscript Latin 188, 1447 –55; Vatican Ottobonensis manuscript Latin 152, 1429 – 1440; Vatican Ottobonensis manuscript Latin 1154, 1530; and Salamanca manuscript Latin 202, pre-1457). These sources too, however, do not end the complication of deciphering an authentic, original text. Though not all complete texts, they are all based on an earlier Latin translation made sometime between the third and fourth centuries. This translation seems to have been made by someone who did not have a solid grasp on Latin. Scholars note that this Latin translation appears to be a literal word for word translation of the original Greek text, often times even preserving the syntactical construction of the original Greek. However, resorting to a literal word-for-word translation is not necessarily a negative point because in the end it has proved helpful in the reconstruction of the original Greek text.

Once a trustworthy text has been established, the problem of interpretation comes to the fore. This is typically a problem initially even for the translator. In an effort to make a text understandable in another language, the translator often times ends up interpreting the text instead of translating it. However, this does not seem to be as much of a problem with Irenaeus’ text, due to the translator’s limited grasp of Latin and the resulting literal translation. Nevertheless, ever since Irenaeus’ writings were translated, his ideas have been interpreted and applied by scholars, both monks and academics. Leaving aside any medieval interpretations of Irenaeus, let us turn to some more recent studies of his thought and writings.

One of the most pervasive themes to continuously arise in Irenaeus’ writings is his staunch defense of the incarnation of Jesus. As previously mentioned, one of the core Gnostic tenets is the denigration of the physical world, claiming that anything material is necessarily evil. Thus, according to the Gnostics, and particularly the docetist group (from the Greek word dokein, which means to seem or appear), Jesus could not have had a physical body. Instead, he only seemed or appeared to have a physical body and thus it was the Gnostic Jesus who merely appeared to die on a cross. Flying in the face of the core Christian belief that Jesus came as a real human person, died a real physical death, and resurrected in a real physical body, Irenaeus adamantly affirms the reality of the human nature of Jesus. In book five he articulates the importance of the physical realm when he reminds his readers that Paul

constantly uses the terms flesh and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, sometimes to show that he was a man (for the Lord himself called himself the Son of man) and sometimes to confirm the salvation of our flesh. For if the flesh were not to be saved the Word of God would not have become flesh (John 1:14) and if the blood of the just were not to be requited the Lord would not have had blood (fn 11: Against Heresies: Book 5, 14.1 in Grant 1997, p. 168).

While Irenaeus’ theological and philosophical motivation, focusing on the incarnation, is agreed upon by most, if not all, scholars (fn 12: See Eric Osborn, Irenaeus of Lyons, Cambridge University Press, 2001; Timothy, 1973, pp. 23 – 39; Gerard Vallee, A Study in Anti-Gnostic Polemics: Irenaeus, Hippolytus, and Epiphanius, Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 1981, pp. 9 – 40; Grant, 1997; and Gustaf Wingren, Man and the Incarnation: A Study in the Biblical Theology of Irenaeus, Muhlenberg Press, 1959), there has been an argument that Irenaeus had more than mere theological / philosophical motives for his treatise.

Gerard Vallee argues in his Study in Anti-Gnostic Polemics that Irenaeus also had socio-political motives for his treatise against the Gnostics (fn 13: cf. pp. 24 –33). Vallee argues that Irenaeus, despite his reputation as a peaceful and permissive pastor, drew the line with the Gnostics due to their threat of disrupting the unity and authority of the church. According to Vallee, upholding the reputation of the church in a society that already distrusted it (indeed, Christians had already experienced a wave of persecutions in Rome) was one of Irenaeus’ major responsibilities. Irenaeus perceived the Gnostics as disruptive and revolutionary, a radical and socially subversive group that needed to be squashed. And so Irenaeus set out to do just that. Successful as he was, however, Gnosticism has continued to be a persistent force with which Christianity has had to deal with over and over again. Nevertheless, Vallee credits Irenaeus for marginalizing Gnosticism, arguing that

In retrospect, the fact that Irenaeus came forward at this time and in the way he did helped Christianity save its identity in the Greco-Roman melting pot. That in turn prevented Christianity from being a marginal movement in the Western world (fn 14: Ibid., p. 33).

Though Christianity did eventually triumph, it has been argued by many for a long time that there was a group within Christianity that was marginalized and thus drawn toward Gnosticism both then and now.

Daniel Hoffman argues in his book, The Status of Women and Gnosticism in Irenaeus and Tertullian, that although Gnosticism has traditionally been presented as much more sympathetic to women than Christianity, there is an abundance of Gnostic texts that would indicate the contrary (fn 15: Hoffman 1995, p. 77: “Exeg. Soul 133,5 says that ‘women led astray the man’ [NHL, 195]; Treat. Seth 65,24-25 warns, ‘Do not become female, lest you give birth to evil’ [NHL, 385]; and The Teachings of Silvanus [NHC VII,4] 93,9-13 mentions that ‘if you cast out of yourself the substance of the mind, which is thought, you have cut off the male part and turned yourself to the female part alone’ [NHL, 385].”). Hoffman goes on to present a strong case demonstrating that “women in second century orthodoxy groups were more highly regarded than in the corresponding Gnostic groups” and even “had a comparatively high status” within orthodox Christian groups (fn 16: Ibid., p. 80). Taking into consideration literary, artistic, and epigraphical evidence, including Irenaeus, as well as more recent studies that have changed the perceived landscape of women’s roles in the early church, Hoffmann emphasizes their involvement in the Christian church as teachers, evangelists, prophetesses, deaconesses, widows, virgins, martyrs, and house church matrons. Though, Hoffmann’s position is definitely controversial, he presents a strong case and brings to light evidence that has all too often been ignored, thus fulfilling his duty as a historian.

Ever since the discovery of a library of fourth century papyrus manuscripts at Nag Hammadi, Egypt in 1945, consisting of 52 treatises in twelve codices and eight leaves from a thirteenth, there has been a revived interest in Gnosticism. The battle between Christianity and Gnosticism, initially brought to the fore by Irenaeus, has been replayed many times since then. From the Gnostic Cathars and Bogomils of the twelfth century, to a renewed fascination with Gnosticism in the twentieth century, demonstrated by the popularity of books like Elaine Pagels’ Gnostic Gospels and Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas, as well as the publishing phenomenon of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, the ideas and teachings of Gnosticism have proven to be a formidable force.

Irenaeus’ work, however, has served the Christian church well over the last two millennium. Hammering out the central importance of the incarnation against docetist Gnostics, playing a pivotal role in the triumph of Christianity over Gnosticism, and even providing a role, though limited, and great respect for women, Irenaeus’ importance for the Christian Church cannot be overestimated. Nor, on the other hand, can his importance in the field of Gnosticism be neglected. In fact, the discoveries at Nag Hammadi have only served to confirm the reliability of Irenaeus’ account in Against Heresies as an accurate source for the wide array of Gnostic teachings flourishing in the first and second centuries.

Indeed, is this not the very goal of our chosen field of study, to constantly strive to paint as accurate a picture as possible of any given period or person, continuously collecting any new evidence to either add new details to our picture, or if need be, to repaint the picture altogether. Anything less is a slippery slope surrounded by all sorts of dangers and this was all too evident in Irenaeus’ day, just as it is in ours. The punk rock band Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols sing it well, “If nothing [is] true, everything [is] possible.”

Originally written in 2004 for a graduate history course with Dr. Craig Miner at Wichita State University.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.