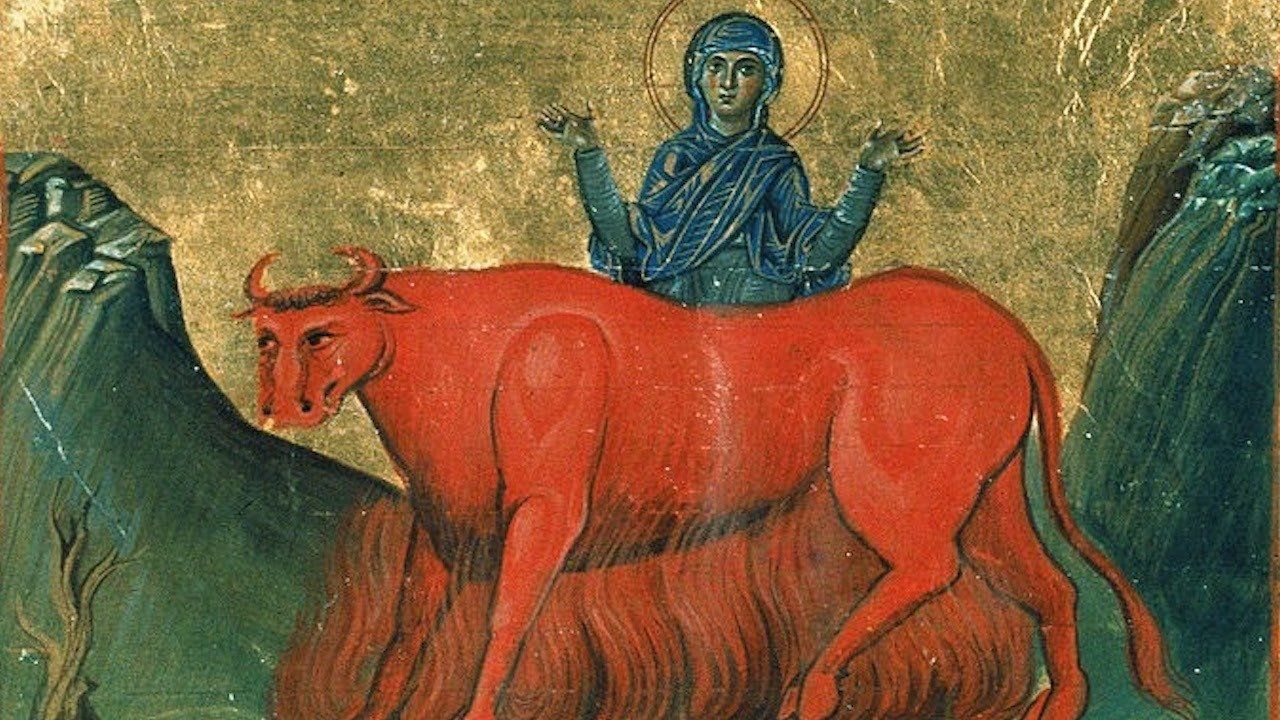

Icon of St. Pelagia of Tarsus burning alive in a metal bull.

1. Essays et al: "Are the Great Books Enough to Revive Our Education System?"

Erik Ellis opens by observing the radical shift in education over the last 100-plus years:

Over this more than hundred-year period, we have seen the once-dominate arts of language and number replaced by the techniques of science. The humanities have been comprehensively subordinated to what are now called the STEM fields. In the institutions of higher education that produce the next generation of educators, critical theory is married to a comprehensive hermeneutic of suspicion that seeks to expose and deconstruct, rather than to form and instruct. Where humanities programs have not wholly abandoned their social duty to train their students to think, speak, and write effectively, they have renamed and redefined their disciplines. Logic has become "critical thinking," rhetoric is "public speaking," and grammar, almost abandoned in English curricula, occupies an ever-shrinking place in foreign language classrooms beset by declining enrollments. And yet, interest in classical education (as well as debate as to what constitutes it) has never been stronger at any point in the last century than it is now. Somehow, children, young people, and adults continue to be inspired by the transcendent vision of truth, beauty, and goodness encapsulated by the Western Tradition, despite the best attempts of educational and governmental policies to redirect their energies towards the flat and mundane technical learning of applied science.

Then, after describing two attempts to revive education through programs focused on the "Great Books" – Dr. Charles W. Eliot’s Harvard Classics ("Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf") and Dr. Mortimer Adler’s Great Books and Socratic Seminars – Ellis turns to one of my great heroes: Dr. John Senior.

Already in the late 1960s, some had begun to see a problem in Adler’s approach: it took little consideration of what the ancients called propaideia or progymnasmata, the culture and discipline-forming practices that had been lost since 1900 and that many in the older generation took for granted. John Senior and his colleagues at the University of Kansas attempted to address this weakness with their short-lived but amazingly influential Integrated Humanities Program, which sought to provide the youth of the 1970s with the experience of reality of which they had been deprived by their suburban upbringing, dominated by mass-media, fast food, and consumerism. Senior argued that before students could profitably read the 100 great books, they needed to have read 1000 good books. Realizing such an ambitious program fell outside the bounds of a two-year general education program, he took his students out into the country to look at the stars and the Milky Way, to learn to dance and sing by firelight, and to memorize and recite the great poetry and tales of a tenuously intact tradition of folk culture.

But are any of these three programs sufficient to renew education? Most everyone knows the progressive system of education is failing. The explosion of homeschooling and classical schools over the last several decades is a great sign for renewal. However, as Ellis notes,

Using the old argument that a liberal education provides its charges with the stability needed to navigate a changing and chaotic world, they have proposed a variety of ways of moving forward by retrieving the wisdom of the past. This has led to myriad pedagogical approaches but little certainty as to what "classical education" is. Everyone seems to recognize that something is wrong with primary and secondary education, but few seem to know to what exactly they are trying to return.

Ellis’s conclusion may not be what you would like to hear, only because there is no easy answer. Without minimizing the importance of reading the great books of the past, he suggests we must first have a thorough and proper understanding of classical education. And that means we must engage in a deep study of the history of education, rather than merely acquiring a superficial understanding through works like Dorothy Sayers’ essay "The Lost Tools of Learning" (don’t get me wrong, that’s a great essay; but it’s only the first rung on a tall ladder of works we should be studying). Ellis concludes:

Once educators have a more thorough knowledge of this history, they will be in a better position to judge whether it is possible or even desirable to implement education’s classical form in order to meet today’s challenges. While the great writings and ideas of the past should of course occupy our minds and our curricula, we should re-examine the foundations of educational culture and see to what extent the disciplines of the past may also be profitably recovered and redeployed.

2. Books & Culture: Suggested Reading and John Senior and the Restoration of Realism

Since Erik Ellis didn’t offer any suggestions for deeper reading on the history of education, I’ll throw out a few titles and then offer you an Eighth Day Books review of a recent book on the life and thought of John Senior. First, a few recommendations:

- A History of Education in Antiquity

by H. I. Marrou and George Lamb

- Norms and Nobility

by David Hicks

- The Crisis of Western Education

by Christopher Dawson

- Poetic Knowledge

by James S. Taylor

And here’s the opening lines to my review of John Senior and the Restoration of Realism:

This is our kind of book. And we agree with Alice von Hildebrand’s foreword, which claims that it "should be in the hands of every educator and every parent." We’d add that it ought to be in the hands of anybody and everybody who cares about culture, be they carpenter or attorney, computer geek or luddite. This is the story of a seed that was planted at the University of Kansas in the 1970s: the Pearson Integrated Humanities Program ("IHP"). According to Fr. Bethel, the program was built on the tenet that reality is real, a "revolutionary" fact for modernity, which was communicated in IHP through the prose, poetry, music, architecture and art of Western culture, in conjunction with the book of Nature.

And be sure to avoid Amazon by turning to

Eighth Day Books

for copies of any of the books referenced above.

3. Bible & Fathers: Feast of the Holy Nun and Martyr Pelagia of Tarsus

Today we commemorate St Pelagia who was born in Tarsus of pagan but distinguished and wealthy parents. Hearing about Christ and the salvation of souls from Christians, she burned with love for the Savior and became utterly Christian in soul. At that time there was a terrible persecution of Christians. It happened that the Emperor Diocletian stopped in Tarsus. During his stay in Tarsus his son, the crown prince, fell deeply in love with Pelagia and wanted to take her as his wife. Pelagia replied through her mother, a wicked woman, that she had already been betrothed to her heavenly Bridegroom, Christ the Lord. Fleeing the profane crown prince and her wicked mother, Pelagia sought and found Bishop Linus, a man distinguished for his holiness. He instructed Pelagia in the Christian Faith and baptized her. Then Pelagia gave away her luxurious garments and great wealth, returned home, and confessed to her mother that she was already baptized. Learning of this and having lost all hope that he would gain this holy virgin for his wife, the crown prince ran himself through with a sword and died. The wicked mother denounced her daughter before the emperor and turned her over to him for trial. The emperor was amazed at the beauty of this young virgin and, forgetting his son, became inflamed with impure passion toward her. But since Pelagia remained unwavering in her faith, the emperor sentenced her to be burned alive in a metal ox, glowing with a red-hot fire. When the executioner stripped her, St. Pelagia made the sign of the Cross and, with a prayer of thanksgiving to God on her lips, entered the glowing ox, where she melted like wax in the twinkling of an eye. Pelagia suffered honorably in the year 287. The remains of her bones were acquired by Bishop Linus and he buried them on a hill under a stone. In the time of Emperor Constantine Copronymos (741-775), on that exact spot a beautiful church was built in honor of the holy virgin and martyr Pelagia, who sacrificed herself for Christ in order to reign eternally with Him.

**All books (and icons) in print available from Eighth Day Books. Please support an independent bookstore that believes in the eighth day resurrection of our God and Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. Give them a call at 1.800.841.2541 or

visit their website here. And don’t forget Eighth Day Members (Patrons+) receive 10% discount, plus many other perks!

Learn more and become a member here.