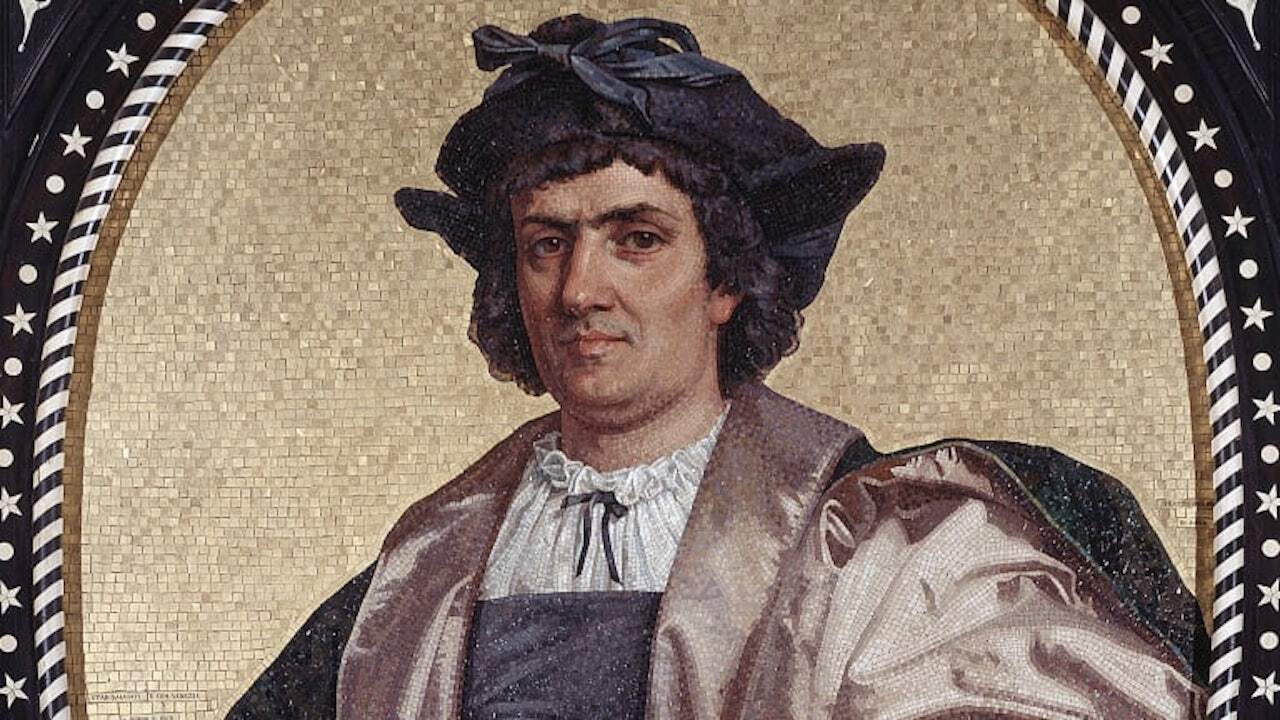

Columbus and the Crisis of the West: Introduction

by Robert Royal

Feast of Our Righteous Forefather Abraham

Anno Domini 2020, October 9

In lieu of a formal review, we'll let Royal's new 2020 introduction peddle this important book:

Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican friar active in the early years of the European missionary efforts in the Americas, earned the name defensor de los Indios (Defender of the Indians) because of his passionate diatribes against exploiters of native peoples in the New World. Along with other philosophers and theologians in Spain, Rome, and elsewhere in the Old Continent, he drew on classical and Christian traditions to argue that the newly encountered peoples were rational beings—human persons—who had rights and warranted respect on both secular and religious grounds. Naturally, his stance drew the ire of vested political and economic interests in Spain, which he stoutly resisted and rebutted. He also knew Christopher Columbus personally and, despite being highly critical of some of the things he did—though not the wild charges of which he typically stands accused today—spoke of his “sweetness and benignity.” And Las Casas defended Columbus as well, against people who blamed him for the disorders and violence that occurred following the first contacts with indigenous peoples. The great explorer’s missteps, he said, were the result of ignorance of divine law and misjudgments about how to proceed: “Truly. I would not dare blame the admiral’s intentions for I knew him well and I knew his intentions were good.”

During the riots that took place in America in mid-2020, several statues of Columbus were toppled. After a statue in Milwaukee fell, video circulated of people—mostly young white women—taking turns stomping on it. This was presumably because they regarded Columbus as the source of the displacement and killing of native peoples and subsequent slavery and racism in the Americas. Whatever the reason, however, it’s quite certain that, unlike Las Casas, the mobs knew little or nothing about the person against whom they raged—or about other figures, including abolitionists, even the black activist Frederick Douglass, whose statues they toppled. And probably did not much care to know, because it has become self-evident to many people, insofar as there is any conceptual basis for such notions, that the whole history of. Western exploration and expansion is nothing but a tale of exploitation, imperialism, and “white” supremacy. If you believe that, prior to any look at the facts—or any sense of the complexity of history—then it also appears wrong to try to sort out the good and the bad present in this process, as in all things human. That amounts, on the radically critical view, to making excuses for genocide and racism.

It used to be possible to assume that any person who had graduated from high school (even grade school) would be familiar with at least a few facts about what happened in 1492. That this is no longer the case reflects failing educational institutions, to be sure, but also—it needs to be said—an anti-American, even an anti-Western and often anti-Christian, ideology that has arisen within the West itself: all the West, because, in 2020, mobs tore down statues in England, France, Belgium, Canada, Australia, and beyond. This widespread unrest calls for careful attention. You don’t need to believe that the French or communist revolutions, for example, were of unmixed benefit to the human race to take the trouble to know dates such as 1789 or 1917 and something about what they mean. Yet the year in which a far greater change came into the world—indeed, began the colossal process by which the various nations and continents truly became one global, interconnected world—has been taught for many years now as something to be ashamed of, even to denounce. In a saner mood, we might regard it as owing to the boldness and tenacity of Columbus, however little gratitude he now gets, that we today inhabit that world.

When the first edition of this book appeared, the contrary view was already starting to take hold. During the 1992 quincentenary of the first voyage of Columbus, which is examined in detail in these pages, many of us who had tried to think through what it meant—both good and bad—found it difficult to say anything positive about it in print, on television and radio, or even in academic settings. In the almost three decades since, scholars have done what they are meant to do: uncovered even more of the rich, sad, inspiring, frightening, appalling, glorious, and inglorious features of the Age of Exploration. But there exists something approaching a taboo about saying anything positive about Columbus or any of the other European explorers. People ready to condemn Columbus for every ill that has occurred on these shores, strangely, would never think of crediting him with the many indisputable goods that have been achieved as well, including the freedom to criticize past and present. And it would not be stretching things to say that the blanket rejection of Columbus has become a symbol for the uninformed repudiation of much of Western—and human—history.

The implications of that repudiation are legion. As historian Wilfred McClay has observed: “The pulling down of statues, as a form of symbolic murder, is congruent with the silencing of dissenting opinion, so prevalent a feature of campus life today. In my own academic field of history, in which the past is regarded as nothing more than a malleable background for the concerns of the present and not as an independent source of wisdom or insight or perspective.” He adds:

Those caught up in the moral frenzy of the moment ought to think twice, and more than twice, about jettisoning figures of the past who do not measure up perfectly to the standards of the present—a present, moreover, for which those past figures cannot reasonably be held responsible. For one thing, as the Scriptures warn us, the measure you use is the. measure you will receive. Those who expect moral perfection of others can expect no mercy for themselves, either from their posterity or from the rebukes of their own inflamed consciences. (“Of Statues and Symbolic Murder,” First Things, 26 June 2020)

Shakespeare’s Hamlet had the old Christian wisdom and mere human decency exactly right: “Use every man after his desert, and who should ‘scape whipping?” (Hamlet II,2)

These truths take on even greater significance if we consider that what is at stake is not merely the historical evaluation of Columbus or Europe or “white privilege.” It goes to the heart of what civilization means: given the universal evidence of human sinfulness and imperfection, we put ourselves in the position of preferring to have no cultural roots at all if we demand to allow into public spaces and permissible discourse only what we believe—on unclear grounds—is now the perfection of moral vision. One of the central things that this book seeks to demonstrate is that the radical critique of the West could not have happened without the very values—equality, human dignity, liberty—that spring from the Western tradition itself, and more specifically the Christian universalism that sees every human person, however imperfect, as a child of God, something that has existed in no other civilization.

Slavery, for example, has been a universal in human history from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to China, classical Greece and Rome, as well as Russia, the scattered kingdoms of Central Africa, the First Nations of Canada, various North American tribes, the great empires of the Mayan and Aztecs, the Ottoman Empire, and the antebellum American South. Chattel slavery—outright “ownership” of other human beings—which is often said to have been invented in the American South, can be dated back at least to the Code of Hammurabi (1750 B.C.) and ancient Egypt. It was almost entirely the work of “white” Christians such as Las Casas, beginning close to the time of the discovery of the Americas, and later British Quakers and Methodists drawing on biblical sources, that slavery was gradually eliminated in almost the entire world. Slavery still exists, of course. Something like forty million people are thought to be enslaved worldwide—but in places where a Christian sensibility is absent or inactive.

It disturbs some people to learn that slavery, genocide, imperialism, and even ritual human sacrifice and cannibalism were present in the Americas long before any European or other outsider ever set foot there. But they were.

Slavery was a part of Native American traditions, both before and after the arrival of Europeans. It was common in the large empires, as in empires on other continents. But it also existed in what is today Canada, particularly the Pacific Northwest, and almost everywhere. As late as the notorious Trail of Tears—the mid-nineteenth century series of forced relocations of several tribes from the American Southeast to West of the Mississippi—there were black slaves, owned by Native Americans, among those making the trek. A 2018 Smithsonian Institution article, “How Native American Slaveholders Complicate the Trail of Tears Narrative,” recalls how awful was that episode, in which at least four thousand died. But also explains:

What you probably don’t picture are Cherokee slaveholders, foremost among them Cherokee chief John Ross. What you probably don’t picture are the numerous African-American slaves, Cherokee-owned, who made the brutal march themselves, or else were shipped en masse to what is now Oklahoma aboard cramped boats by their wealthy Indian masters. And what you may not know is that the federal policy of Indian removal, which ranged far beyond the Trail of Tears and the Cherokee, was not simply the vindictive scheme of Andrew Jackson, but rather a popularly endorsed, congressionally sanctioned campaign spanning the administrations of nine separate presidents. (Smithsonian Magazine, March 6, 2018)

There was Native American genocide as well, even among groups for whom any decent person will today feel a great deal of sympathy. For instance, on July 4, 2020, controversy erupted over the American presidents represented on Mount Rushmore and even the U.S. government’s ownership of the site. But the history of the place tells a melancholy tale. In 1776, the very year the American colonies declared their independence, the Lakota Sioux conquered the Black Hills, where Mount Rushmore is located. they wiped out the local Cheyenne, who held it previously; and the Cheyenne had taken it themselves from the Kiowa, who took it from … no doubt some other tribe. As one informed historian pointed out: “The Lakota-Sioux arrived in the West after being on the losing end of a war with other tribes in Minnesota in the late 1700s. Known as the Lakota, or simply the Sioux, they waged genocidal war on other tribes before they took over the Black Hills from the Cheyenne…. They did the exact same thing that the United States did to drive the Lakota out” (Tom Correa, “The Last Tribe to Get the Black Hills,” The American Cowboy Chronicles (blog), April 18, 2015).

It is very difficult to escape the network of human evils that have existed throughout history. The African American author Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a highly influential book in 2015 on the history of racism and white supremacy, Between the World and Me, in the form of a kind of message to his son, Samori. The son was named after a late-nineteenth-century African leader, Samori Ture, a devout Muslim who fought French colonialism in West Africa—but also captured and sold black slaves to finance his empire building. In so doing, he was carrying on a tradition—black Africans capturing and selling other black Africans as slaves to others—that predated the Atlantic slave trade by at least a thousand years and continues in various forms of human trafficking even today.

To recall such things is not to excuse Europeans or Christians who should have behaved better then and still should now. But it is to get a clearer picture of what we as a species have been, rather than fictional representations of purely good and purely bad actors that have displaced the truth.

It is common today to charge historically Christian nations with violence or religious bigotry not only toward Native Americans but even toward Muslims. During the riots of 2020, one Islamic group called for renaming Saint Louis, Missouri, because the French king after whom the city is named, Louis IX (1214-1270), had fought against both Jews and Muslims and, in fact, had been captured and imprisoned by Muslims in Egypt during the Seventh Crusade. In modern pluralistic societies, where large numbers of people with very different beliefs must try to live together in some sort of civic orderliness, such religious tensions obviously need to be avoided. But it is not so easy to transpose postmodern American concerns into the Middle Ages, let alone the Age of Discovery.

Few Westerners know it, but in 1453—less than forty years before Columbus arrived in the Caribbean—the Ottoman Turks finally overthrew Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire for over a thousand years, and continued with further advances. This process had a long history. Muslims had conquered much of the Middle East and all of North Africa and made repeated incursions into the Holy Land, Spain (for eight hundred years), Rome, Sicily (where they ruled for almost a century), and elsewhere. It is no surprise, then, that Louis IX fought Muslims, even as he was beyond all dispute one of the most saintly and charitable of men. In the context of his time, preventing Muslim advances preserved Christian civilization. Had he and others failed, European and American cultures might today resemble the Middle East, and the voyages of discovery might never have occurred.

The downfall of Constantinople in 1453 sent shockwaves throughout Europe and, in Spain, one reason why Ferdinand and Isabella, by fits and starts and finally in 1492, expelled Muslims was fear of Ottoman support for rebels. And it did not stop there. Muslim invaders pressed on into the Balkans and other Western territories, even reaching Vienna, where they were turned back only with some strokes of good fortune, primarily the last-minute arrival of Polish hussars, in 1683.

If revisionist views of European nations in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance have sought to make them look like nothing so much as Game of Thrones, recent scholarship about pre-Columbian America makes much of the New World appear not so very different. Our picture of native peoples in the English-speaking world has been strongly shaped by images of the relatively thinly settled Indian lands that the English colonists encountered (especially after diseases from Europe felled large percentages of native communities). It was from them that we derived the notion of the “noble savage,” physically fit, independent, living lightly on the land. That picture is not entirely wrong—for a rather small segment of indigenous populations. It depends, however, on focusing on small tribes (all of what is now New England held only about one hundred thousand natives in the early 1600s, about one-sixth the current population of Boston) and ignoring continual tribal warfare, with its scalpings, kidnappings, and torture of captives. Most of the native settlements along the New England shores, for example, were protected by ramparts from attacks by warriors of other tribes.

When it comes to the large city-states and even empires that have been uncovered in Meso- and South America in recent decades, the argument for a universal human nature (and not an entirely happy one) across differences of culture, place, and age gains significant support. People who have actually look into, say, Aztec civilization know that Tenochtitlán—the core of today’s Mexico City—appeared to the earliest Spanish explorers, some of whom had sailed to the most opulent Mediterranean cities, as far richer in buildings, population, foodstuffs, and various cultural achievements than any city in Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It was also the center of an empire—perhaps containing as many as five million people—built by conquest over neighboring peoples and dependent on human sacrifice to bloodthirsty gods who required human blood to maintain the equilibrium of the world.

The other great civilizations of the Americas—Olmecs, Toltecs, Maya, Incas—also produced impressive urban centers and political, economic, and social networks, so much so that, as archeaologists and others have uncovered the remains of those civilizations, estimates of the population of the Americas have soared wildly. Some of the increase is doubtless owing to the desire of some scholars to compensate—overcompensate, say other scholars—for the relatively small numbers once thought accurate. Estimates now range from 8 million to almost 120 million inhabitants. Obviously, discrepancies of more than an order of magnitude called into question the methodologies used to produce them. But that large urban centers existed with extensive networks and surrounding areas to feed and supply them is now beyond dispute.

It is beyond dispute that, like other human population centers, these cities were not situated in an unsullied earthly paradise. They cultivated but also depleted natural resources. They fought typical wars of conquest with one another. They rose, flourished, declined, and disappeared, just like human habitations in other parts of the world. Most practiced slavery. They changed large features of the natural landscape—from the high altitude of Mexico City to the riverbanks of the Amazon. That a much more idealized version of native peoples has survived all these discoveries reflects a hunger in postmodern Western culture for something “other” and purer. But projecting your needs onto other peoples and ignoring their actual lives dehumanizes them in a sense. No people will long be held in esteem—once real history enters into the picture—if they are held up as an unreal idealization that has never existed since the Garden of. Eden, owing to the sinfulness, limited vision, and weakness of our universal human nature.

That applies to current critics of the past as well. If you are going to pull down statues of Columbus because he and the culture out of which he came were imperfect, what ideals will you offer for the future? In a review of the first edition of this book (titled 1492 and All That: Political Manipulations of History), Oxford historian J. H. Elliot suggested that it was regrettable that a book like this even needed to be written (“The Rediscovery of America,” New York Review of Books, June 24, 1993). But it did. And it still does—now partly rewritten and amplified to reflect some of the historical work that has been done in intervening years and to freshen arguments that may prevent us from making rash and destructive judgments.

A remarkable shift in how we view human history has become dominant since this book first appeared. for several centuries in the West, there has been a widespread belief in human progress, driven by science, technology, and pragmatic uses of reason. There remained some sense that great men—Columbus, Newton, and Jefferson among them—could alter the course of history. As the first chapter of this book outlines, Americans caught up in that progressive movement were happy to falsify the historical record in order to portray the Genoese explorer as a kind of precursor of later rebels who defied the received wisdom of religion and tradition to forge new paths for the human race. In that reading, Columbus was the forerunner of the Protestant Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, global capitalism, even the modern autonomous self. That reading was not true (Columbus was a thoroughly medieval Christian extrapolating from the geographical knowledge available for the most part since Greco-Roman times). But that misappropriation of Columbus did at least retain some sense of the daring and imagination that went into. Columbus’s voyages—and the global developments they unleashed. Much of that understanding, as is documented here, simply melted away in the anti-Western ideological triumphs of the past fifty or so years. Columbus has become, for many today, a blank slate on which to project the loves and hatreds of our time: Euro-centrist, racist, imperialist, “genocidal maniac,” and so on.

But there is even worse. Not only has the old Western confidence in progressivism, unreliable and incomplete and. deluding a vision though it was, collapsed into its mirror image, but a crushing materialism, joined incoherently with visions of a technologized human future, has replaced it. There’s no better example of the process than the wild, worldwide success of a book such as a Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens, which dismisses virtually all of previous history as a mere prelude to a posthuman future that seems to leave him and millions of readers untroubled, though untethered to anything recognizably congenial to Homo sapiens. In its own strange way, that detachment from everything in the past paradoxically represents a kind of culmination of the anti-Western, anti-historical purity that makes up the bulk of the story told in this book.

Part of the difficulty in properly assessing Columbus the man is that it took a complex and driven figure to carry out what, eventually, he did. So it is possible to say he was ambitious—because he was. And sought honors—which he did—and wealth too. And that there were religious motives mixed in with these others. Columbus, like many in his time, was a strong believer whose faith deepened as he grew older—not exactly an unknown phenomenon even today. But his religious side has looked, at least to the cynics, as either a hypocritical cover for worldly motives or a benighted medieval superstitiousness that he had clung to well into what was then the Renaissance. Yet the notion of preaching the gospel to all nations and using the riches of the East to recover Jerusalem from the Muslims, however strange an inspiration for modern eyes and ears, made perfect, even sublime, sense in his world.

A modern reader need not be a believer to understand that the mentality of someone—and such an unusual someone—in a different age, half a millennium ago, should not be reduced to categories that come easily to mind for us. Indeed, anyone who wants to understand both the man and the things he achieved—and did not achieve—should expect to have to step outside of at least some habitual assumptions. If that does not happen, we will be proceeding under a schizophrenia that afflicts much of the Western world today: on the one hand, we take the principles of human dignity as self-evident—which they are not, anywhere outside the Christian-inspired civilization of the West. And at the same time, we will repudiate the very source of the things we hold as most morally certain.

The author is quite aware that there are many people who do not care about such efforts, who want only to feel the thrill of sweeping moral condemnations of imperfect historical figures, figures who, like us, were deeply shaped by their own times, by contemporary insights and blindness—and occasional steps toward something greater than they could yet articulate. Yet even if a work like the present one may not much affect our current civilizational crisis, civilization depends on unrelenting efforts to pursue truth, however unpopular, over uninformed emotion.

And besides: the history of both Native American peoples and the Europeans who came to these shores is much more humanly interesting and instructive than simple morality tales.

*From Robert Royal, Columbus and the Crisis of the West (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2020), 3-16. Purchase your copy from Eighth Day Books.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.