2019 Inklings Lecture: Introduction to the Sacramental Imagination of George MacDonald

by Vigen Guroian

Feast of St Domna of Tomsk

Anno Domini 2020, October 16

In his introduction to Greville MacDonald’s biography of his father, G. K. Chesterton states that George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin “made a difference to [my] whole existence.” The reason, he explains, is that “of all the stories that I have read,” it is “the most realistic, in the exact sense of the phrase the most like life.” “It helped me to see things in a . . . way,” he continues, that the later “revolution” in my “religious allegiance” to Roman Catholicism “only crowned and confirmed.”

This is a lot to claim for a children’s story, a fairy tale! In order to understand Chesterton’s meaning, let’s begin with his statement that The Princess and the Goblin was “the most realistic” and “most like life” of all the books he had read. By “realistic” we can be sure that Chesterton does not mean naturalistic, or what, in literary terms, is often named social realism. That surely is not it. Rather, MacDonald has in mind something religious, something having to do with what I shall call the sacramental imagination.

For, in fact, Chesterton was especially taken by the manner in which The Princess and the Goblin depicts how an “other” world, in this case, the world of “fairie,” breaks into our mundane world, or, allegorically stated, in which the spiritual world penetrates and transforms the world in which we live. In our story a castle-like farmhouse, home to the princess Irene, the story’s chief protagonist, is emblematic of our world. Listen for a moment to Chesterton’s own summation of the story. The Princes and the Goblin

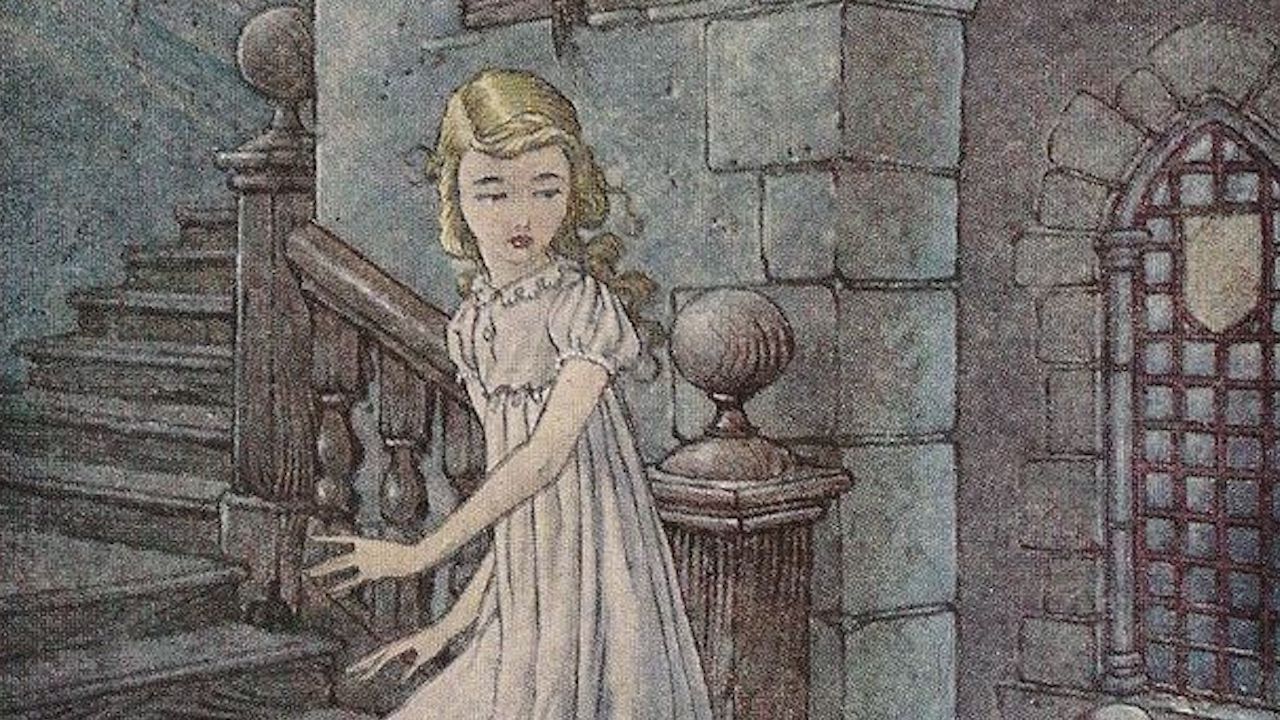

describes a little princess living in a castle in the mountains which is perpetually undermined, so to speak, by subterranean demons who sometimes come up through the cellars. She climbs up the stairways to the nursery or the other rooms; but now and again the stairs do not lead to the usual landings, but to a new room she has never seen before, and cannot generally find again. Here a good great-grandmother, who is a sort of fairy godmother, is perpetually spinning and speaking words of understanding and encouragement. When I read it as a child, I felt the whole thing was happening inside a real human house, not essentially unlike the house I was living which also had staircases, rooms and cellars. (In Defense of Sanity, 301-302).

That “whole thing” of which Chesterton speaks may be summed up in one word: mystery. Mystery enters this house, mystery is in this house, and this is what makes the story so true to life. There will be those who find this claim puzzling, if not downright absurd. After all, isn’t the coexistence of the real and the mysterious a non sequitur? Surely, modern people have gotten past superstition, and area able to distinguish what is real from that what is fanciful.

Yet Flannery O’Connor, that gifted twentieth century American writer of fiction, agrees with Chesterton over and against the secularist weltgiest. She argues that people who believe “the reaches of reality end very close to the surface, that there is no ultimate divine source, that things do not pour forth from God,” have clipped their own wings, are looking at life through the wrong end of a telescope. “The type of mind,” she continues, “that can understand good fiction . . . is the kind of mind that is willing to have its sense of mystery deepened by contact with reality, and its sense of reality deepened by contact with mystery” (Mystery and Manners, 79).

Chesterton argues that MacDonald “did really believe that people were princesses and goblins and good fairies, . . . [though] he dressed them up as ordinary men and women.” As God truly is present in this world, so, analogously in The Princess and the Goblin, MacDonald portrays “fairie “as inside an ordinary house, in a garden, and underneath a mountain. In the world of his story, which might just as well be our world, an ordinary staircase, the very staircase Irene scampers up, can be a Jacob’s ladder leading to heaven. Indicative of just this sort of thing, when Irene enters her great grandmother’s attic bedroom, she finds that in the center of the room hangs “a lamp as round as a ball, shining as if with the brightest moonlight. . . . The walls were . . . blue—spangled all over with what looked like stars of silver” (87).

Chesterton reads MacDonald allegorically. God intends us all to be princes and princesses in his church, in his heavenly kingdom.

*Originally delivered at the fifth annual Inklings Festival on October 18, 2019. Full lecture delivered to all Eighth Day Members with 2020 Inklings Lectures and Seminars.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.