Why Does Suffering Befall Us?

by Bishop Irenei

Feast of Our Holy Father Clement, Pope of Rome

Anno Domini 2022, November 24

Why? Why do certain agonies befall us?

One of the most perplexing questions that faces us is that of why God might permit us to suffer in certain ways or circumstances. Indeed, a substantial portion of the grief and despair that is often associated with suffering comes not from the actual elements of the suffering itself (i.e., from physical pains of the body or the mind), but from the question that arises in our soul when the suffering becomes acute: “Why, O Lord, are You letting this happen to me?” The desire to have an explanation, to seek a cause-and-effect rationale for what might seem unjust or unfair, and certainly unpleasant, produces a mental anguish that can be as strong as any physical ailment that actually inflicts us—and at times can even overpower it.

Philosophers and theologians have struggled with seeking answers to this “problem of evil” for millennia. Why do the good suffer? Why does an all-powerful and all-merciful God permit grief and sorrow to exist? Why cannot He Who orders all things, order His creation so that there is no suffering, nor pain, nor any agony? And there have been myriad “answers” to this problem posed over the centuries: some defeatist, some optimistic; some rationalistic, some more spiritual. There are issues of human freedom at stake; there are matters of deception by evil powers; there are questions of coming-into-being and going-out-of-it; and there are “solutions” to the problem of evil and suffering that can be drawn out of all these elements.

But none of these ultimately satisfies, because what we are dealing with is—as others before have said—not really a “problem” in any traditional sense. Problems are fundamentally things that have “solutions.” They presuppose situations that can be fixed, dilemmas that can be solved. But suffering is not a “problem” in this way; it is a mystery. It is a strange effect of life in a world that is in the hands of God, yet also in ours. It has no “solution,” no inspiringly compelling explanation (though we can, of course, account theologically for its existence). Instead, suffering is something that we address, not by accounting for it or “solving” it, but by entering into the experience of it, and allowing that experience to be redeemed and become redemptive.

Suffering befalls us, therefore, not always as a mathematical or logical consequence to anything we have done; and God permits this to be so, not out of an arbitrariness or a lack of love. Suffering has the power, despite its origin so often in tragedy, to draw us into a better character of life—and this God permits, for He knows that it can change us. If Christ is truly the “cornerstone” of our life, then we are given strength and stability in the very circumstances that might otherwise overwhelm us. That which might grind us to powder (Matt. 21:44; Lk. 20:18), instead becomes that by which we are built up into something greater.

This is a lesson learned long ago in the Church. In the Sayings of the Desert Fathers we read, “Abba Poemen believed that the only time you could observe a person’s true character was when that person was tempted.” Do you see how the saint perceives temptation, not as being intrinsically detrimental to our spiritual life, but in fact something that can reveal the true state of our heart? The encounter with temptations, even if these include great spiritual and physical suffering, can disclose to us that which remains hidden away when “all is well” and we are comfortable with our lives. Suffering opens the reality of the heart—what is good within it, as well as what is bad and requires healing. In such a circumstance the life of the Gospel is tested and made perfect—for that which is tested is tried, and that which is tried becomes stronger, like iron in the forge (cf. Is. 48:10), and the weakness of man’s nature is made mighty and capable of bearing the grace of God.

The positive opportunities brought by suffering, moreover, do not come only through specific, deliberate trials that God may place on our path through fore-ordained actions. Even certain accidents (a term which many Christians people fear to use, but which the saints do not), which bring suffering in their wake, have the power to awaken us to the stirrings of a deeper life.

St. Herman of Alaska, who experienced both tremendous sufferings as well as a great many tragedies in his missionary works, wrote:

A terrible accident has a power to awaken us to the realization of the existence of various calamities and dangers surrounding us, from which the Providence of God preserves us. At the same time it convincingly persuades us to acknowledge our own infirmity and weakness, and to seek the Father’s protection and His most powerful defense, which affirms us in the Wisdom and the Word of God, which came down from above by the will of the Heavenly Father under a curtain of flesh like ours, woven by the Divine Might from the Immaculate Virgin, for our salvation. He became man and taught us to pray that we be not led into temptation. This reminds us from what Father we have our existence, and this in turn should make us seek our heavenly Fatherland and our eternal inheritance. (Letter to Baranoff, 1809)

Thus, says the saint, God allows even the unfortunate accidents of life in this broken world to afflict us—for good. We must see in St. Herman’s example, in particular, the powerful witness of his faith and experience. This was a man who had seen the power of God in ways that, to many, seem almost mythical: holding back the sea, staving off fires and winds, and so on. But even for one who had with his own eyes beheld such things, St. Herman is profoundly aware of our sinful insensitivity to God’s constant work in our lives. We take “peace and calm” for granted, and fail to see how every second of peace is a gift of God; how every instant, every fraction of a moment of calm and tranquility, is a divine protection afforded by Christ and the ever-ready intercessions of His holy Mother. The arrival of some accidental calamity, St. Herman says, invites us to become more readily aware of how fragile, and how precious, is the life of peace offered us by God. It is an invitation to make every moment of our lives one in which the seeking of our heavenly Fatherland is front and center of our attention.

Some suffering, we must readily acknowledge, comes to us neither by the Lord’s personal design, nor by accident, but by the work of others. The demons never tire in their efforts to drive us from God by magnifying our sufferings and distorting our response to them. But even suffering that has its source in the demons can be redemptive!

St. Maximus the Confessor speaks eloquently of this:

There are said to be five reasons why God allows us to be assailed by demons. The first is so that, by attacking and counterattacking, we should learn to discriminate between virtue and vice. The second is so that, having acquired virtue through conflict and toil, we should keep it secure and immutable. The third is so that, when making progress in virtue, we should not become haughty but learn humility. The fourth is so that, having gained some experience of evil, we should “hate it with perfect hatred” (cf. Ps. 138:22, LXX). The fifth and most important is so that, having achieved dispassion, we should forget neither our own weakness nor the power of Him who has helped us. (Four Hundred Texts on Love, Second Century, 67)

When the demons attack, St. Maximus says, even though their aim is our destruction and the despair of soul that would rend us away from God through personal rebellion, fear and the rejection of love, nevertheless even in these moments God has not released His grip on us. The pain which comes through such assaults might utterly destroy us if we were left unaided in meeting it; but God takes the assaults of the demons and allows them to teach us to distinguish good from evil, to love what is good through the experience of its opposite, to be humbled and learn to crave humility rather than pride (for it is our pride that opens the door to the demons’ influence in the first place), and in all things to see how the power of God sustains us and lifts us up.

We see, my beloved ones, that suffering befalls us for many reasons and from many sources. Some suffering comes from God, Who rebukes and chastises those whom He loves (cf. Ps 11:5 KJV); some comes from the world; some from ourselves; some from the demons. But whatever its origin, the suffering that we receive in faith is that which can save us. Think of it! Even the devil’s worst threat—that of suffering and torment and pain and grief—is something that God can turn into redemption and grace!

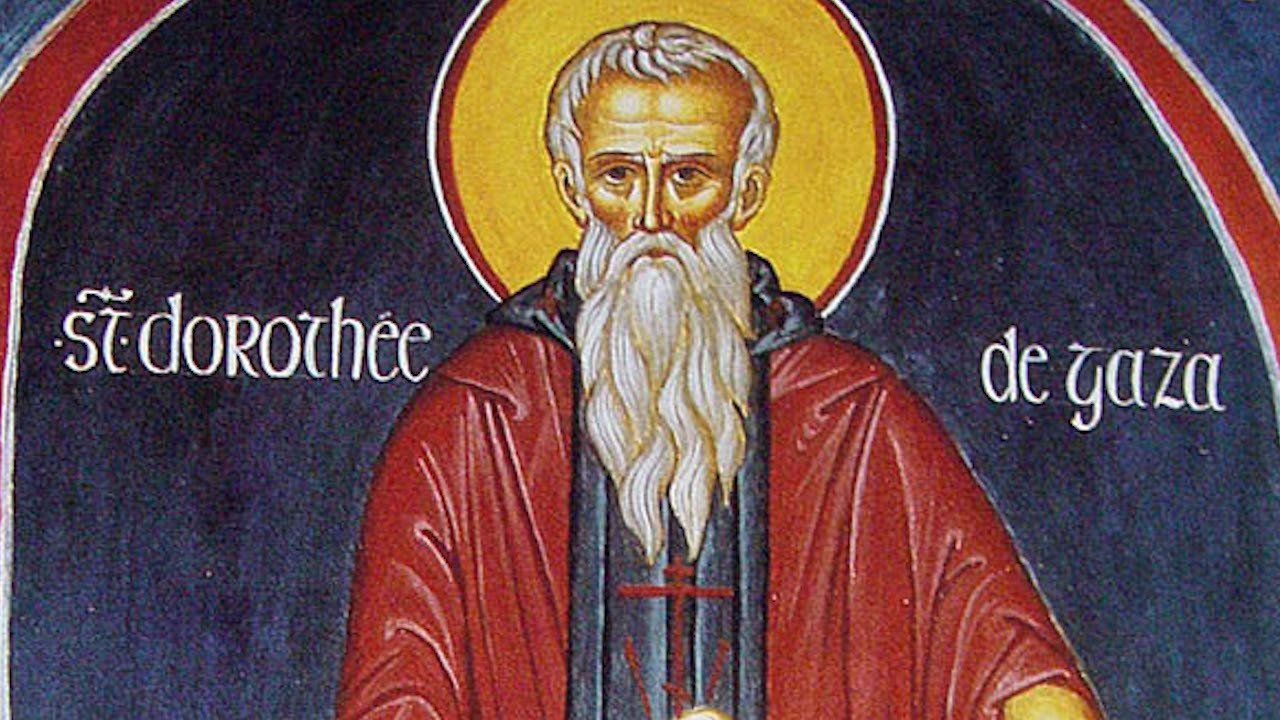

We should remember the words of St. Dorotheos of Gaza, who said: “Even if we cannot endure much labor because we are weak, let us be set on humbling ourselves” (Discourses and Sayings). To be humbled by suffering is not a curse; it is a thing to be received with thanksgiving—and we receive it as such not simply for romantic reasons of exercising trust and hope, but because we learn from our Fathers that it can bring us true repentance and draw us closer to God’s love. This is a love that overpowers the soul-destroying potential of any suffering, and instead renders it a thing that brings us more firmly into His embrace. It matters not what form the suffering takes. Or what intensity. Pain, agony, grief and death may try to rend us from our Maker’s arms, but the love of God is only received more strongly in these moments of trial. As the Apostle St. Paul so famously said:

If God be for us, who can be against us? Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? As it is written, “For Thy sake we are killed all the day long; we are accounted as sheep for the slaughter.” Nay, in all these things we are more than conquerors through Him that loved us. For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Rom. 8:31, 35-39)

*Chapter 4 from Strength in Weakness (Safford, AZ: St Paisius Monastery, 2020), pp. 33-42. Available for purchase at Eighth Day Books.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.