WE ARE

going to end this evening’s Nativity Feast with a reading that we’ve now done ten years in a row. You could say it has become an Eighth Day tradition. Just as St John Chrysostom’s Paschal Catechetical Oration

is ready every year in the Orthodox Church on Pascha (Easter), every year at the EDI Feast of the Nativity we read St. Gregory the Nazianzus’s Oration 38, On the Nativity / Theophany.

But before that reading, let me first say a few words about St. Gregory Nazianzus and St. Maximus the Confessor, thereby adding two more heroes to the cloud of witnesses for this evening’s celebration (the others being St. Athanasius, W. H. Auden, G. K. Chesterton, and David Jones)

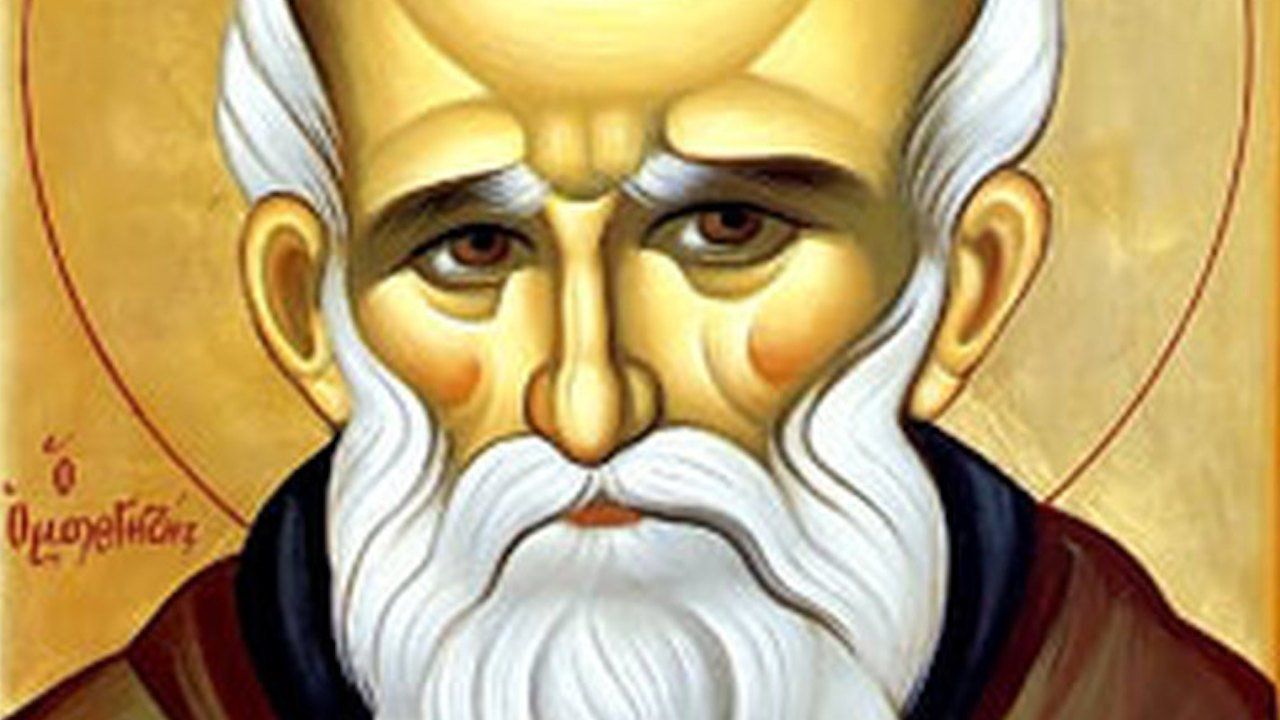

St. Gregory the Theologian

St. Gregory of Nazianzus (329-390) has been given numerous titles, including “Thunder of Dogmas,” “Divine and Sacred Head,” “Eye and Voice of the Universe,” and “Palace of Eloquence.” But most famously, he is only one of three saints to whom the Church has given the title “Theologian” (St. John the Evangelist and St. Symeon the New Theologian are the other two).

Here is how St. Gregory was described in the fourth and the eleventh centuries:

O Gregory, thou art a man in body but an angel in spirit…. For thy lips praise God like one of the Seraphim, and enlighten the universe with the teaching of true faith. Therefore, accept me who comes to thee with love and faith and be my teacher and enlightener. ~Eusebius (4th cent.)

Every time I read St Gregory, and I often have occasion to do so, chiefly for his teaching but secondarily for his literary charm, I am filled with a beauty and grace that cannot be expressed. […] The beauty of his works is not of the type practiced by the duller sophists, epideictic and aimed at an audience, by which one might be charmed at first and then at the second contact repelled—for those orators did not smooth the unevenness of their lips and were not afraid to rely on boldness of diction rather than skill. But his art is not of that kind, far from it; instead it has the harmony of music.

~Michael Psellos (11th cent.)

You’ll hear that harmony of music firsthand shortly.

After the Bible, St. Gregory is the most frequently cited author in all of Byzantine ecclesiastical literature. He is most known—especially in the West—for his Five Theological Orations

in which he responded to the radical Arian theology of Eunomius, which attributed full divinity only to the Father.

After retiring from public life as archbishop of Constantinople and bishop of Nazianzus, he spent much of his solitude composing poems—theological, moral, and autobiographical—and editing collections of his letters and forty-five of his orations. By the 9th century, sixteen of those orations had been chosen to be read on feast days, saint’s days, or as commentary on the Gospel text for the day.

During the century between his birth (A.D. 329) and the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (A.D. 451), where he was officially given the title “Theologian,” there was an explosion of commentaries on his writings. His orations are highly rhetorical and, unlike his fellow Cappadocians (St. Basil the Great and St. Gregory of Nyssa), according to Fr. Maximus Constas, “he theologized in a more ‘literary’ mode, delivering himself of charismatic, near-oracular utterances whose laconic obscurity and polysemic allusiveness were not easy to grasp—and likely to be misunderstood—without informed analysis and interpretation.” For the interpretation of that “laconic obscurity and polysemic allusiveness” we turn to St. Maximus the Confessor.

St. Maximus the Confessor

The earliest works of St. Maximus the Confessor (A.D. 580-662) were written primarily to correct influential but non-orthodox doctrines of Origen and his disciples. Maximus’s Chapters on Love

(A.D. 626) rewrites nearly one-hundred Evagrian passages, shifting Evagrius Ponticus’s emphasis from human knowledge to divine love. The Ambigua, his next work which he began in A.D. 628, according to Fr. Maximus Constas, “set out to transform the theology of Origen and Evagrius, not simply in the flower of its language, but in its deepest roots, effectively securing Christian asceticism and spirituality on solid theological, philosophical, and anthropological foundations."

Philosophically and theologically, the Ambigua

is Maximus’s greatest work. It is where his genius and creativity as a theologian shines most brilliantly. Essentially two works in one—Ambigua to Thomas

and Ambigua to John—it’s written in a literary genre that was popular in monastic and philosophical circles: Questions and Answers. And both parts are Maximus’s attempt to clarify “ambiguous” passages (or comment on "the difficulties") in the writings of St. Gregory the Theologian

.

Ambigua

31-38 all reflect on parts of Gregory’s Oration 38, On the Nativity. I’ve highlighted four of the “ambiguous” phrases in the passage we’ll be ending with (see below). For this occasion, we'll focus on Ambigua

33 (also see below) in which St. Maximus offers an explanation of the Theologian’s phrase “the Word is made dense [or thick].” Before ending with the reading of Oration 38, let's see how Maximus explains Gregory.

Maximus says St. Gregory the Theologian had three ideas in mind:

1) Quite simply, to instruct us “by means of words and examples.” Christ teaches us both through His words and His deeds.

2) The Word becomes thick by concealing (or incarnating) Himself in the logoi of beings. All of creation is stamped by the Divine Logos, that is to say, there are logoi (principles/rationales) that reflect the Logos in everything. In Maximus’s words, the Logos remains

- Without origin in things that have a beginning

- Invisible in things that are seen

- Incapable of being touched in all that is palpable

But why?

3) For the sake of our thick minds, the Logos consented to be embodied and expressed through letters, symbols, and sounds. According to St. Maximus, “So that from all these things He might gradually gather those who follow Him to Himself, being united by the Spirit, and thus raise us up to the simple and unconditional idea of Him, bringing us for His own sake into union with Himself by contraction to the same extent that He has for our sake expanded Himself according to the principle of condescension.”

In his earlier Ambiguum

10, reflecting on St. Gregory’s oration on St. Athanasius, Maximus had already used this same idea of “becoming thick”: “the Word, who for our sake became like us and came to us through the body, and likewise grew thick in syllables and letters.” Notice the repetition of thickness in syllables and letters. In other words, the Word of God doesn’t just become thick by taking on our flesh, or by stamping all of creation, but also by embedding Himself in words and syllables and letters.

In summary, St. Maximus illustrates the three ways Christ became dense by using the image of a garment:

- Christ took on the garment of flesh.

- The forms and shapes of created things that our physical eyes behold are also garments of flesh, which are stamped with the principles—the logoi—that reflect their Creator, the Logos.

- Similarly, the words in Holy Scripture are garments. According to Maximus, the inner meaning of those words—logoi—are the “fleshes” of the Word—the Logos.

In that same Ambiguum

10, St. Maximus offers some of his most important reflections on the Transfiguration of Christ. Drawing that feast together with the Feast of the Nativity according to the Flesh of our Lord, God & Savior Jesus Christ which we celebrate this evening, the admonition to us from both St. Maximus and St. Gregory (as well as St. Athanasius, W. H. Auden, G. K. Chesterton, and David Jones!) is to follow Peter, James, and John up the mountain of the divine Transfiguration where we can behold the garments of the Word in His Incarnate Body, in all of His creation, and in all of His words of Scripture, all of which, according to St. Maximus, are “shining and glorious in their reciprocal teachings” about the eternal Son and Word of God, the Divine Logos.

Now for St. Gregory’s Oration!

*Erin Doom

is the founder and director of Eighth Day Institute. He lives in Wichita, KS with his wife Christiane and their four children, Caleb Michael, Hannah Elizabeth, Elijah Blaise, and Esther Ruth.

**Originally delivered at the 11th annual Feast of the Nativity in the Year of Our Lord 2020 in Wichita, KS at The Ladder, headquarters for Eighth Day Institute.