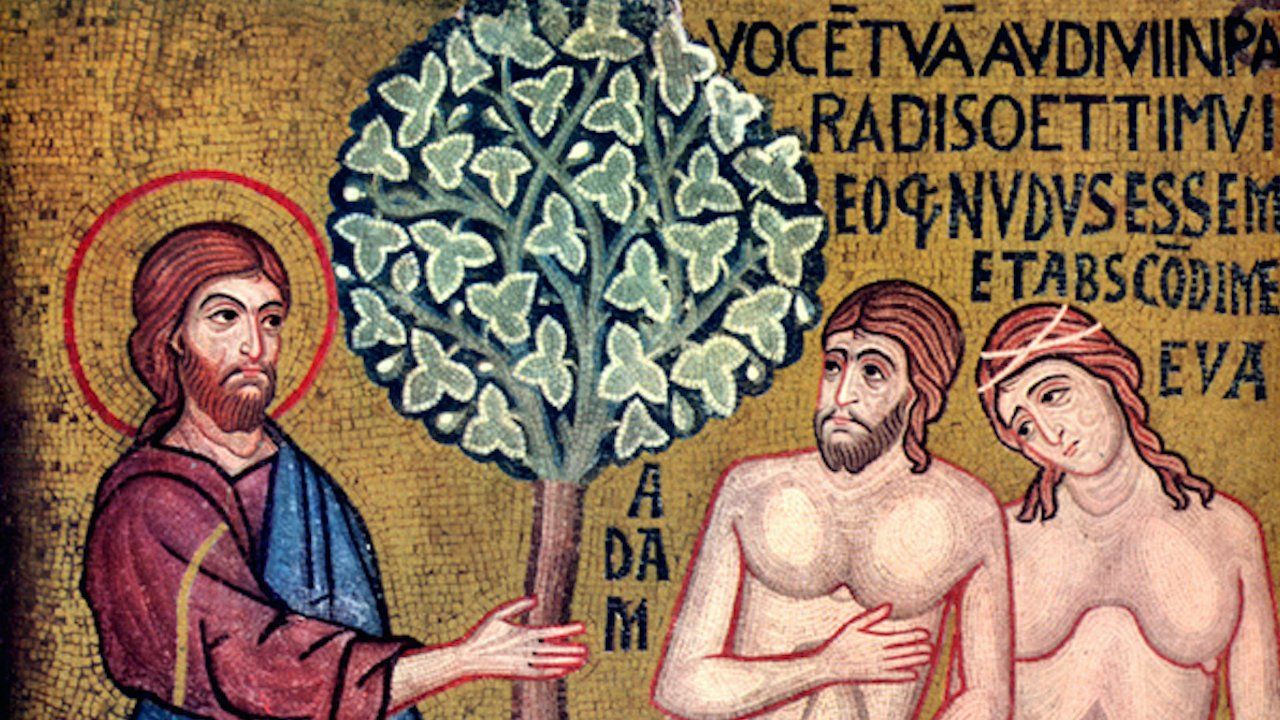

The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

by Dumitru Staniloae

Feast of the Blessed Andrew the Fool-for Christ at Constantinople

Anno Domini 2020, October 2

According to the interpretation of the fathers, the knowledge of good and evil, acquired when the activity of the senses unites with the sensible aspect of the world, consists in a knowledge of the passions born in the human person, while according to the special interpretation of St. Basil, it consists also in the fight against these passions. From the patristic interpretations we see that on account of the Fall, the human person was left with the knowledge of evil in himself but overwhelmed by it. He continued to be opposed to evil but could not succeed in bringing his struggle to a victorious conclusion.

From the fact that the state of disobedience as estrangement from God is reciprocally involved with the passionate impulse that takes its birth from the weaving together of sensuality and the sensible aspect of the world, a more complex understanding of this sad knowledge of good and evil results, that is, of the fall of man.

Disobedience, pride, and our own selfish appetite arise as a weakening of the spirit. These, moreover, produce a restriction on the knowledge of God’s creation; the human person looks to what he can dominate and to what can satisfy his bodily needs and pleasures, now become passions. the bodily passions, in turn, will feed the pride in the human person that satisfies them. His exclusively material needs and passions will be a source of pride justified by his proud claim to be autonomous.

We should note that in our description of this restricted knowledge of creation, we have already passed on to the consequences of sin, inasmuch as this restricted image of the world in a particular way, but in part, too, this restricted knowledge (which both hold sway within man against his will) are no longer produced by an actual sin.

This restricted knowledge is adapted to an understanding of the world as ultimate reality, but as a reality characterized as object and destined to satisfy exclusively the bodily needs—now become passions—of rational creatures. It conforms to the human passions and pride under whose power it has fallen, and it sees creation as a vast, opaque, and ultimate object possessed of no transparence or mystery that transcends it. This knowledge took its origin from a spiritually undeveloped human person, and it has remained at his measure, arresting his spiritual growth in relation to the horizon that lies beyond the sensible world. It is a knowledge that veils what is most essential in creation, hence a knowledge in the ironic sense that God uses to speak of in Genesis 3:22. It is a knowledge that will never know the ultimate meaning and purpose of reality.

The difficulty of coming to know the transparent character of creation and of person itself, characters that open their infinite meanings, derives also from the fact that creation and the human person can no longer put a stop to the process of corruption that leads each human person toward death. Had Adam not sinned, the conscious creature would have advanced toward a kind of “stable” motion within a greater and greater convergence and unification of the parts of creation, of the human person in himself and of humans among themselves and with God, within a movement of universal love whereby creation is overwhelmed by the divine Spirit. Instead, through the Fall, a motion toward divergence and decomposition entered creation. It is only through Christ, as God incarnate, that the parts of creation have begun to recompose themselves so as to make possible its future transfiguration, for from Christ the unifying and eternally living Spirit is poured out over creation.

We note that in the Orthodox view, the world after the Fall did not take on a totally and fatally opaque image, nor was human knowledge wholly restricted to a knowledge that conformed to an opaque, untransparent image of the world. Humans can penetrate this opacity in part by means of another kind of knowledge, and indeed, they often manage to do this, but they cannot wholly overcome this opacity and the knowledge that conforms to it. These remain dominant structures.

We have seen, moreover, that the world has a meaning only because, being malleable, it can be led toward a mode of existence that is higher and eternal, toward the perfect truth or good that consists in love and union between God and the world, between humans and God, and among humans themselves.

Creation has been ordered in such a way that it might be a place where God can speak and work with this purpose in view and where we can respond to God through our words and deeds and set out on the path of this developing communion that God has willed. Creation fulfills its purpose when it continues to remain a place wherein our human being can undertake a dialogue of some sort with God. For this dialogue can grow only if the world continues to be seen, at least in part, as a gift of God, a foundation for the higher gift of salvation through which the world will be delivered from its present state of corruptibility and death.

The world was originally created with the qualities that correspond to this purpose. Through the Fall it became to a large extent opaque, and the withdrawal of the divine Spirit from the world weakened the character it had as transparent medium between God and humans and among humans themselves. Because the Spirit has withdrawn both from the world and from the human person, the world no longer keeps its original malleability, nor does the human person preserve that force of spirit whereby he can lead the world toward a state in which it serves fully as a means of communication between God and himself and between himself and his fellow humans. At every point within each causal series the world still allows for the choice of many causal directions, indeed even for the realization of certain effects which surpass the effects that lie within the power of natural causality. But the world no longer affords the possibility to make easy use of the whole of its malleable character, while among humans it is rare to find those who by their efforts acquire enough spiritual force from their link with the divine energy as to overcome natural causality itself and open up an exit from it and at the same time a prospect of the future dawning of the full meaning of existence and of the fullness of life, goodness, and genuine spirituality.

Yet, even through these rare breakthroughs to the higher horizon of integral good, we have the feeling that this kind of breakthrough could be achieved in a peremptory manner if only our spiritual powers were reunified and reinforced and if reason were always united with love. But in the insufficient union of reason and love in the weakening of each by their separation, and in the divergence between them, which permits no fully penetrating love, no full realization of good, we feel the presence of sin. In paradise Adam could see with a mind that was full of love, with a soul filled with the power of the divine Spirit, and this not only because he himself was completely unified, but also because he lived in a creation that was full of the divine Spirit. No separation existed between creation and the world of the divine energies, no contradiction among the tendencies of man, no separation between these and the higher divine powers. Adam had open before him the endless dimensions of these depths and was able with no difficulty to remain on the steps leading toward the good. Creation, opening up as it did on the infinite, protected him from being cornered in any way and did not seem a narrow, enclosed reality to the human person. Because it was associated with rationality, creation spread wide its dimensions to their fullest meaning, for human existence had not yet been cut back by death.

For those who raise themselves in Christ from this narrowness of creation, death does not have the last word. Existence is extended beyond death into the infinite. For them rationality acquires its full meaning, and so does existence. They see the assurance that they will continue eternally in virtue of the worth of their own person, which they feel. The eternal value of the human person is assured by the fact that the supreme basis itself of existence, as the human being’s partner in eternal communion and love, is personal in character. The return of the human being to communion with God delivers him from eternal death.

By renouncing communion with God and with his fellow humans, the human being has limited his knowledge to knowledge of the world as object. He has grown weak in knowledge of the divine subject who is superior to the world, for knowledge of the divine subject comes about through communion with God and never gives man the possibility of being sovereign over him. In wishing to know everything in a completely or merely rational manner, the human being is left with only that aspect of the world and of the human body that understands humans as objects. Left with a narrowly rational knowledge of nature and of his fellow humans, the human being has detached knowledge from the understanding of creation as the gift of God and from the love of God as the one who is continuously bestowing creation as gift, providing the human being with his neighbors as partners in a dialogue of love.

There can be no denying, however, that knowledge of the rationality of nature through the mediation of human reason represents in its own way a development of the human spirit. Thus, here, too, we have an ambiguity, a simultaneous growth and reduction of our powers symbolized by the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

The exclusively rational knowledge of the world to which man has been reduced and which comes to him by separating, limiting, and generalizing does not provide him with knowledge of the whole of existence, nor does it obtain for him the spiritual life in its integrity, for it leaves the human being outside of communion with the supreme Subject and with his fellow humans as subjects. It leaves him bereft of eternal life and lacking in the prospects of knowing an eternally new reality, prospects assured by communion with the supreme Subject and with one’s fellow subjects.

St. Gregory of Nyssa drew attention to the surprising fact that besides the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the “tree of life” was also to be found in the very midst of paradise (The Making of Man, 19-20). This implies that both of them were found in the same central point, for there cannot be two central points. The meaning might be that one and the same world, when grasped exclusively by means of the senses and by reason placed at the service of the senses, is the source of the of good that is not good; whereas, when grasped in its real significance by a reason that sees more deeply and instead places the senses in its own service, it becomes a source of life. Therefore, the “tree of life” is either the same world grasped by “mind,” or else God who comes to be seen through the world grasped in this way. A “tree of life” is the person of anyone else who is the source of my life through the love he shows me, while the “Tree of life” all-inclusively and par excellence is the absolute Person as the source of endless love for all and the source of the love all persons have among themselves.

In this case a question would arise: in what sense does Genesis say that God drove Adam and Eve out of paradise after the Fall so that they would not eat from the “tree of life” and live? How could they still eat of the world through “mind” and live, once fallen away from this capacity? Did not the world cease to be a “tree of life” through the very fall of man? Or was the “tree of life” not hidden away by the Fall in the depth of the world? Perhaps that is exactly what Genesis means, even though it attributes this result to a special act of God. Adam and Eve had fallen from the vision of God into a world that had become untransparent and because God had withdrawn from their sight. God does not behave passively when confronted by their fall; they are driven away from the tree of life by a separate act withdrawing this tree from the possibility that they might see it. The world becomes untransparent and brings forth death and corruption not because of the human deed alone, but also because of the act of God who withdraws some of his energies from the world. The fact that the tree of life is said to have remained somewhere from which humans have been removed may mean that in itself the world remained potentially a tree of life and potentially transparent, but that men had fallen away from knowing it in this way. They no longer saw the world as a “garden,” as a paradise of the fullness of life through which God was “walking”; they no longer saw the world in its meaning as open to the personal infinity of God. It is significant that the saints who, through Christ, have raised themselves above the exclusive attachment to creation see in creation features and dimensions hidden from those who know only the world. St. Symeon the New Theologian, for example, described the orders of eternal life, which he saw in part even in this life, in colors of unutterable beauty and harmony. We can say that it is precisely those who cling exclusively to the surface of creation who lose the vision of its profundity in God, who lose the world as tree of life and as chalice inviting us to take the immortal divine life. These are the people who stand outside the world as the “garden” through which God is walking and who go on living in a world that brings forth “thorns and thistles” alongside the wheat, a world of sweat and exertions, a world of pleasures mixed with pain.

*Excerpted from The Experience of God – Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Volume Two: The World: Creation and Deification, translated by Ioan Ionita and Robert Barringer (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthdox Press, 2000), pp. 170-177. Available for purchase from Eighth Day Books.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.