ONE OF THE

best books I’ve read on patristic theology is The Suffering of the Impassible God: The Dialectics of Patristic Thought

by Paul L. Gavrilyuk. The book is a historical study of impassibility, an early Christian doctrine that claims God does not suffer human emotions or feelings.

Gavrilyuk frames his whole argument as an apologetic toward the school of thought that he labels “The Theory of Theology’s Fall Into Hellenistic Philosophy,” which becomes his shorthand for the following:

A standard line of criticism places divine impassibility in the conceptual realm of Hellenistic philosophy, where the term allegedly meant the absence of emotions and indifference to the world, and then concludes that impassibility in this sense cannot be an attribute of the Christian God. In this regard, a popular dichotomy between Hebrew and Greek theological thinking has been elaborated specifically with reference to the issues of divine (im)passibility and (im)mutability. On this reading, the God of the prophets and apostles is the God of pathos, whereas the God of the philosophers is apathetic.

In short, the line of reasoning goes, the Bible depicts a God who suffers; Greek philosophy, one who does not. With this as your starting point, which do you choose? Of course, forced into this dichotomy, you choose the suffering God of the Bible.

Gavrilyuk shows clearly that this theory—that the church fathers imposed some foreign theology onto the New Testament gospel that wasn’t unearthed until the Reformation or the advent of historical-critical exegesis actually—has very little historical warrant. There was simply no consensus about these things even in Hellenistic philosophy. What the church fathers were really doing in their encounters with various forms of heresy, especially in the Sabellian, Docetic, Arian, and Nestorian controversies, was articulating a negative theology, hence the subtitle The Dialectics of Patristic Thought. In other words, they were safeguarding the inexhaustible mystery of the transcendent God. They weren’t capitulating to certain ideas dominant in their society; they were fighting to prevent certain erroneous conceptions of the person of Jesus Christ.

I encountered "The Theory of Theology’s Fall Into Hellenistic Philosophy" in two forms at my evangelical seminary: (1) a New Testament exegesis professor repeatedly told his students to “be careful” reading the church fathers because they uncritically accepted theoretical and metaphysical thought forms foreign to the Bible (and I’ve encountered this caricature dozens of times since, almost always from within the “biblical studies” guild), and (2) an applied theology professor sympathetic to the trinitarian thought of Jürgen Moltmann and Eberhard Jüngel (a few prime suspects, following Harnack, when it comes to Gavrilyuk’s Theory) appropriated their ideas in a very practical way.

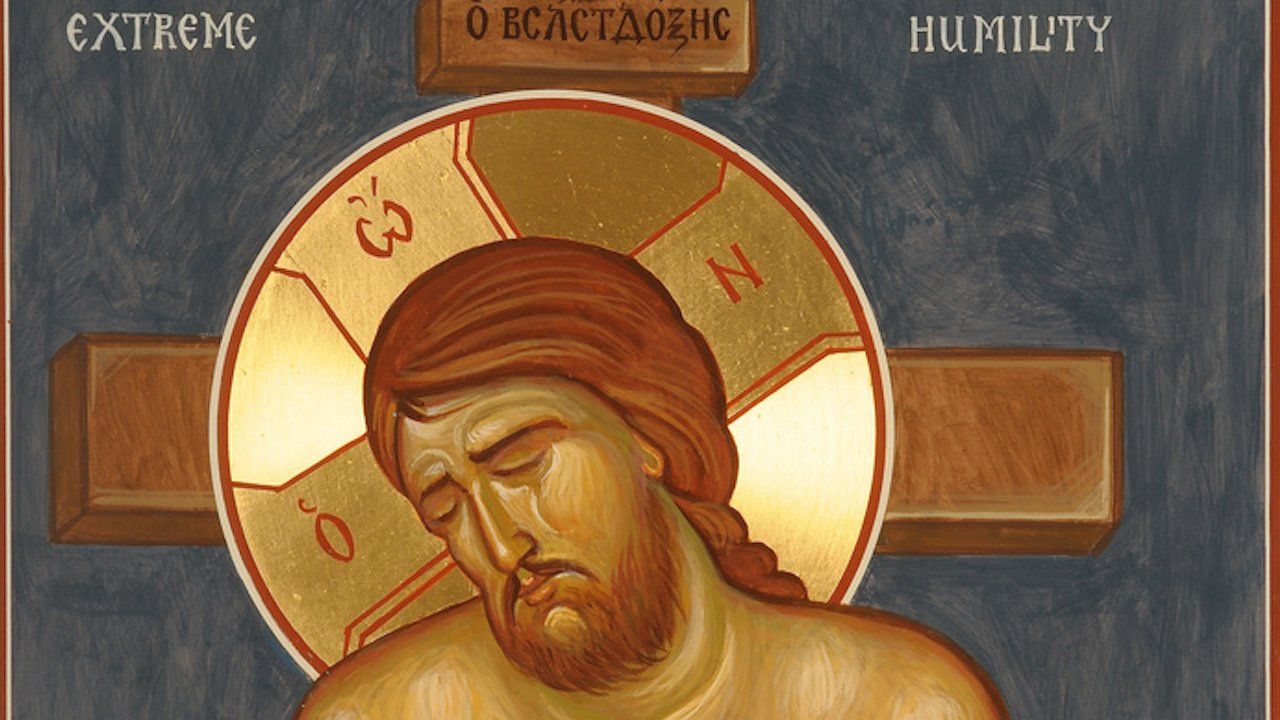

So does God suffer? Well, yes and no. Literally. Cyril of Alexandria, who articulated the doctrine in its most fleshed out form, used the formula “the impassible God suffered” in Jesus Christ as his theological crux in his debates with the Nestorians. Any attempt to resolve this paradox ultimately results in heresy.

The answer beyond that is that Jesus Christ suffered in his human nature, but not in his divine nature. His divine nature was involved in the sufferings of Jesus, because Jesus’s human and divine natures were, after all, inseparably joined. But in suffering, Jesus did not merely identify with human suffering but overcame it through his divinity. A God who merely identifies with human suffering isn’t capable of saving us from it.

Moreover, and this is something almost all critics of impassibility miss, Gavrilyuk points out again and again that impassibility does not simply mean God is incapable of all emotions, but is rather incapable of the type of emotions that are not historically defined as “God-befitting,” such as grieving and despair. Otherwise, again, how would he overcome them for our salvation?

It’s been exciting over the past decade to see more and more historical and systematic theologians—Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox—taking on both the assumed fall of Christian theology into some kind of dark age after the New Testament era and the near-consensus among modern systematic theologians and biblical scholars that God suffers in his very being. This book is a pretty focused and dense theological monograph, so I hope these ideas continue to catch on at a more popular level.

224 pp. paper $55.00

Exercise the virtue of patience, resist Amazon, and support Eighth Day Books. Give them a call at 1.800.841.2541 between 10 am and 8 pm CST Mon-Sat and engage in a conversation about books and ideas with a live human person who reads books and loves to discuss them. Or, if you insist, visit their website at www.eighthdaybooks.com.

Jeff Reimer

is a freelance editor and writer based in Newton, Kansas.