The Rise of Modern Scientific Culture & Modern Social Unrest

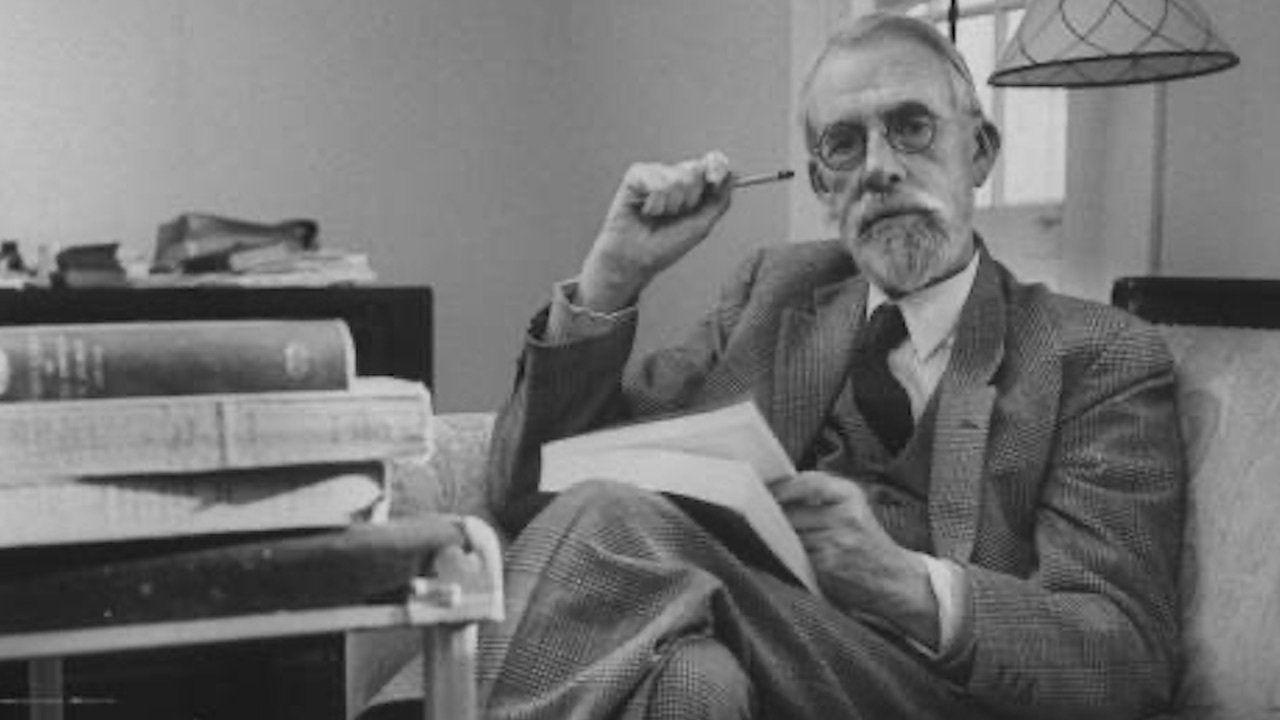

by Christopher Dawson

Feast of St Aquila the Apostle among the 70

Anno Domini 2022, July 14

The Rise of the Modern Scientific Culture

A ferment of change, a new principle of movement and progress entered the world with the civilization of modern Europe.

The development of the European culture was, of course, largely conditioned by religious traditions the consideration of which lies outside the limits of this inquiry. It was, however, not until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that the new principle, which characterized the rise of modern civilization, made its appearance. It was then that there arose—first in Italy and afterwards throughout Western Europe—the new attitude to life that has been well named Humanism. It was, in fact, a reaction against the whole transcendent spiritualist view of existence, a return from the divine and the absolute to the human and the finite. Man turned away from the pure white light of eternity to the warmth and color of the earth. He rediscovered nature, not, indeed, as the divine and mysterious power that men had served and worshipped in the first ages of civilization, but as a reasonable order which he could know by science and art, and which he could use to serve his own purpose.

“Experiment,” says Leonardo da Vinci, the great precursor, “is the true interpreter between nature and man.” Experience is never at fault. What is at fault is man’s laziness and ignorance. “Thou, O God, dost sell us all good things for the price of work.”

This is the essential note of the new European movement; it was applied science, not abstract, speculative knowledge, as with the Greeks. “Mechanics,” says Leonardo again, “are the Paradise of the mathematical sciences, for in them the fruits of the latter are reaped.” And the same principles of realism and practical reason are applied in political life.

The state was no longer an ideal hierarchy that symbolized and reflected the order of the spiritual world. It was the embodiment of human power, whose only law was Necessity.

Yet no complete break was made with the past. The people remained faithful to the religious tradition. Here and there a Giordano Bruno in philosophy or a Machiavelli in statecraft gave their whole-hearted adhesion to Naturalism, but for the most part both statesmen and philosophers endeavored to serve two masters, like Descartes or Richeleiu. They remained fervent Christians, but at the same time they separated the sphere of religion from the sphere of reason, and made the latter an independent autonomous kingdom in which the greater part of their lives was spent.

It was only in the eighteenth century that this compromise, which so long dominated European culture, broke down before the assaults of the new humanists, the Encyclopedists and the men of the Enlightenment in France, England, and Germany. We have already described the attitude of that age to religion—its attempt to sweep away the old accumulation of tradition and to refound civilization on a rational and naturalistic basis. And the negative side of this program was, indeed, successfully carried out. European civilization was thoroughly secularized. The traditional European polity, with its semi-divine royalty, its state Churches and its hereditary aristocratic hierarchy, was swept away and its place was taken by the liberal bourgeois state of the nineteenth century, which aimed, above all, at industrial prosperity and commercial expansion. But the positive side of the achievement was much less secure. It is true that Western Europe and the United States of America advanced enormously in wealth and population, and in control over the forces of nature; while the type of culture that they had developed spread itself victoriously over the old world of Asia and the new world of Africa and Oceania, first by material conquest, and later by its intellectual and scientific prestige, so that the great oriental religion-cultures began to lose their age-long, unquestioned dominance over the daily life and thought of the peoples of the East, at least, among the educated classes.

Progress and Disillusionment the Meaning of Modern Social Unrest

But there was not a corresponding progress in spiritual things. As Comte had foreseen, the progressive civilization of the West, without any unifying spiritual force, and without an intellectual synthesis, tended to fall back into social anarchy. The abandonment of the old religious traditions did not bring humanity together in a natural and moral unity, as the eighteenth-century philosophers had hoped. On the contrary, it allowed the fundamental differences of race and nationality, of class and private interest, to appear in their naked antagonism. The progress in wealth and power did nothing to appease these rivalries; rather it added fuel to them, by accentuating the contrasts of wealth and poverty, and widening the field of international competition. The new economic imperialism, as it developed in the last generation of the nineteenth century, was as grasping, as unmoral, and as full of dangers of war, as any of the imperialisms of the old order. And, while under the old order the state had recognized its limits as against a spiritual power, and had only extended its claims over a part of human life, the modern state admitted no limitations, and embraced the whole life of the individual citizen in its economic and military organization.

Hence the rise of a new type of social unrest. Political disturbances are as old as human nature; in every age misgovernment and oppression have been met by violence and disorder, but it is a new thing, and perhaps a phenomenon peculiar to our modern Western civilization, that men should work and think and agitate for the complete remodeling of society according to some ideal of social perfection. It belongs to the order of religion, rather than to that of politics, as politics, were formerly understood. It finds its only parallel in the past in movements of the most extreme religious type, like that of the Anabaptists in sixteenth-century Germany, and the Levellers and Fifth-Monarchy Men of Puritan England. And when we study the lives of the founders of modern Socialism, the great Anarchists and even some of the apostles of national Liberalism like Mazzini, we feel at once that we are in the presence of religious leaders, whether prophets or heresiarchs, saints or fanatics. Behind the hard rational surface of Karl Marx’s materialist and socialist interpretation of history there burns the flame of an apocalyptic vision. For what was that social revolution in which he put his hope but a nineteenth-century version of the Day of the Lord, in which the rich and the powerful of the earth should be consumed, and the princes of the Gentiles brought low, and the poor and disinherited should reign in a regenerated universe? So, too, Marx, in spite of his professed atheism, looked for the realization of this hope, not, like St. Simon and his fellow-idealist Socialists, to the conversion of the individual and to human efforts towards the attainment of a new social idea, but to “the arm of the Lord,” the necessary, ineluctable working-out of the Eternal Law, which human will and human effort are alike powerless to change or stay.

But the religious impulse behind these social movements is not a constructive one. It is as absolute in its demands as that of the old religions, and it admits of no compromise with reality. As soon as the victory is gained, and the phase of destruction and revolution is ended, the inspiration fades away before the tasks of practical realization. We look in vain in the history of United Italy for the religious enthusiasm that sustained Mazzini and his fellows, and it took very few years to transform the Rousseauan idealism of revolutionary France, the Religion of Humanity, into Napoleonic and even Machiavellian realism.

The revolutionary attitude—and it is perhaps the characteristic religious attitude of modern Europe—is, in fact, but another symptom of the divorce between religion and social life. The nineteenth-century revolutionaries—the Anarchists, the Socialists, and, to some extent, the Liberals, were driven to their destructive activities by the sense that actual European society was a mere embodiment of material force and fraud—magnum latrocinium [great robbery], as St. Augustine says—that it was based on no principle of justice, and organized for no spiritual or ideal end; and the more the simpler and more obvious remedies—republicanism, universal suffrage, national self-determination—proved disappointing to the reformers, the deeper became their dissatisfaction with the whole structure of existing society. And, finally, when the process of disillusionment is complete, this religious impulse that lies behind the revolutionary attitude may turn itself against social life altogether, or at least against the whole system of civilization that has been built up in the last two centuries. This attitude of mind seems endemic to Russia, partly, perhaps, as an inheritance of the Byzantine religious tradition. We see it appearing in different forms in Tolstoy, in Dostoevsky, and in the Nihilists, and it is present as a psychic undercurrent in most of the Russian revolutionary movements. It is the spirit which seeks not political reform, not the improvement of social conditions, but escape, liberation—Nirvana. In the words of a modern poet (Francis Adams), it is

To wreck the great guilty temple,

And give us Rest

And in the years since the war, when the failure of the vast machinery of modern civilization has seemed so imminent, this. view of life has become more common even in the West. It has inspired the poetry of Albert Ehrenstein and many others.

Mr. D. H. Lawrence has well expressed it in Count Psanek’s profession of faith, in The Ladybird (pp. 43-4).

I have found my God. The god of destruction. The god of anger, who throws down the steeples and factory chimneys.

Not the trees, these chestnuts, for example—not these—nor the chattering sorcerers, the squirrels—nor the hawk that comes. Not those.

What grudge have I against a world where even the hedges are full of berries, branches of black berries that hang down and red berries that thrust up? Never would I hate the world. But the world of man—I hate it.

I believe in the power of my dark red heart. God has put the hammer in my breast—the little eternal hammer. Hit—hit—hit. It hits on the world of man. It hits, it hits. and it hears the thin sound of cracking.

Oh, may I live long. May I live long, so that my hammer may strike and strike, and the cracks go deeper, deeper. Ah, the world of man. Ah, the joy, the passion in every heartbeat. Strike home, strike true, strike sure. Strike to destroy it. Strike. Strike. To destroy the world of man. Ah, God. Ah, God, prisoner of peace.

It may seem to some that these instances are negligible, mere morbid extravagances, but it is impossible to exaggerate the dangers that must inevitably arise when once social life has become separated from the religious impulse.

We have only to look at the history of the ancient world and we shall see how tremendous are these consequences. The Roman Empire, and the Hellenistic civilization of which it was the vehicle, became separated in this way from any living religious basis, which all the efforts of Augustus and his helpers were powerless to restore; and thereby, in spite of its high material and intellectual culture, the dominant civilization became hateful in the eyes of the subject oriental world. Rome was to them not the ideal world-city of Virgil’s dream, but the incarnation of all that was anti-spiritual—Babylon the great, the Mother of Abominations, who bewitched and enslaved all the peoples of the earth, and on whom, at last, the slaughter of the saints and the oppression of the poor would be terribly avenged. And so all that was strongest and most living in the moral life of the time separated itself from the life of society and from the service of the state, as from something unworthy and even morally evil. And we see in Egypt in the fourth century, over against the Hellenistic city of Alexandria, filled with art and learning and all that made life delightful, a new power growing up, the power of the men of the desert, the naked, fasting monks and ascetics, in whom, however, the new world recognized its masters. When, in the fifth century, the greatest of the late Latin writers summed up the history of the great Roman tradition, it is in a spirit of profound hostility and disillusionment: Acceperunt mercedem suam [they have received their reward], says he, in an unforgettable sentence, vani vanam [vanity of vanities; cf. Augustine, Sermon 12 on Ps 118].

This spiritual alienation of its own greatest minds is the price that every civilization has to pay when it loses its religious foundations, and is contented with a purely material success. We are only just beginning to understand how intimately and profoundly the vitality of a society is bound up with religion. It is the religious impulse which supplies the cohesive force which unifies a society and a culture. The great civilizations of the world do not produce the great religions as a kind of cultural by-product; in a very real sense, the great religions are the foundations on which the great civilizations rest. A society which has lost its religion becomes sooner or later a society which has lost its culture.

What then is to be the fate of this great modern civilization of ours? A civilization which has gained an extension and wealth of power and knowledge which the world has never known before. Is it to waste its forces in the pursuit of selfish and mutually destructive aims, and to perish for lack of vision? Or can we hope that society will once again become animated by a common faith and hope, which will have the power to order our material and intellectual achievements in an enduring spiritual unity?

Excerpted from “Religion and the Life of Civilization” in Enquiries into Religion and Culture (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2009), pp. 89-94. Available for purchase at Eighth Day Books. Originally published in 1933 by Sheed and Ward. This essay was originally published in William Loftus Hare, ed., Religions of the Empire: A Conference on Some Living Religions within the Empire (London: Duckworth, 1925), pp. 455-469.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.