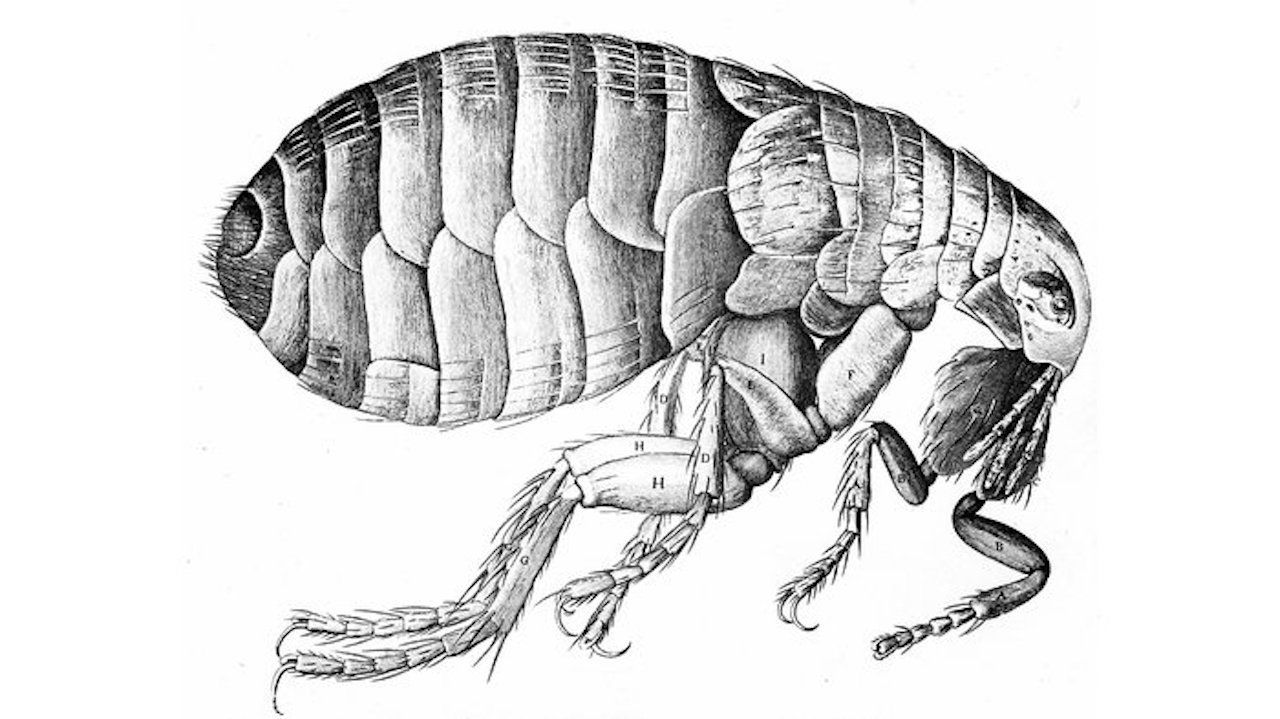

Flea illustration by Robert Hooke in his 1665 publication Micrographia.

Definitions & Famous Plagues

“A plague” is a general term indicating an infectious pandemic. “The Plague” is specific to epidemics and pandemics concerning the bacterium Yersenia Pestis. Multiple times throughout history “the Plague” occurs in the world.

The Justinian Plague

(A.D. 541-544) was the first historically recorded plague, killing 25-100 million people in the Byzantine Empire (equivalent to about half of Europe’s population at the time of the outbreak). It was literally responsible for the fall of the last Roman Empire and split the “center” of the world of the Roman-Byzantine Mediterranean into Islamic Mesopotamia and Christian Europe. The Plague followed trade by ship from Alexandria to Constantinople to the British Isles.

The Great Plague

or the “Black Death” (A.D. 1347 - 1357) wiped out 50-60% of the European population (approximately 40-50 million people). It actually originated in Central Asia in the early 1300’s where a third of the population died and then spread to Europe along shipping trade routes.

The Plague in China

(A.D. 1855 – 1959) was the third major bubonic plague. It spread to all inhabited continents killing 12 million people. Of those 12 million deaths, approximately 10 million were in India.

The Plague also occurred in the U.S. in Los Angeles (1919-1925).

*Dates for Plague vary because the disease does not abruptly stop but continues sporadically.

Social Conditions for the Plague

There are three primary social conditions:

- Unsanitary urban crowding (rats) with cooler moist weather.

- International trade and travel (vectors spread quickly by ship).

- Lack of medical understanding (may have increased spread).

Black Rats and Oriental Rat Fleas

There are four players in “the Plague”:

- The cause is the bacteria Yersenia Pestis.

- The carrier is the Mediterranean black rat (Rattus rattus).

- The vector is the Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopsis).

- The flea bites the human recipient (who can also be a vector).

Yersenia Pestis

is a gram-negative bacteria that lives in some rodents (rats, squirrels, marmots) at a chronic low level but does not kill them.

2,500 species of flightless types of fleas exist, each having its own specific host (a particular warm-blooded mammal upon which they prefer meals). The oriental rat flea gets its blood meal preferentially from the “black rat” as a requirement to trigger ovarian and testicular maturation in the flea. The fleas must “drink before having sex.”

The oriental rat flea can become infected with the Yersenia Pestis

bacteria when it bites the infected black rat. Multitudes of the Yersenia Pestis

bacteria begin to reproduce and live in the foregut of the flea. There are so many bacteria in the foregut that the digestive tract of the flea is mechanically obstructed by the collection of bacterium. The flea begins to starve to death and frantically takes more blood meals, which in turn feeds the Yersenia

in an orgiastic feast rivaling anything in the bathhouses of Rome. The flea is active only in a very narrow range of temperatures: 59-68 degrees Fahrenheit (one reason it may have spared Arabia).

A single rat is home to hundreds if not thousands of fleas, with a portion of those fleas infected with Yersenia

bacteria. Each time the flea bites the rat, it injects up to twenty thousand bacteria into the rodent’s bloodstream. The original black rats, which were infected and carried the fleas to Constantinople during the Justinian Plague, were believed to have come from Egypt on boats of grain, which is the rat’s favorite feeding source. In the Great Plague (Black Death) the same black rat and flea are believed to have been onboard twelve ships in the 1300’s coming from the Black Sea to Europe as part of the Oriental Trade Route.

The oriental rat flea does not usually feed off of human blood, but if rats are not immediately available (or dead) and the human is close, humans will be bitten as a proximate food source. Fleas do not fly, so they typically jump and bite the ankles or lower legs. They cling to fur, so the feet may be somewhat spared in lieu of the lower legs (this was the reason women began to shave their legs….kidding).

The other ways that humans can be infected with Yersenia Pestis

is by direct contact of contaminated fluid, blood, or dead tissue of another human being or dead animal (e.g., the corpses of the “Black Plague”).

A final way of infection is by large droplet or airborne spread causing pneumonia (e.g., a cough or sneeze or even talking at close range). This was not discovered until 1924 in Los Angeles.

Better means of public health sanitation, less rats, and the use of antibiotics have virtually eliminated epidemics in the U.S. and Europe. There are still occasional infections in the Southwestern U.S. among rodents or squirrels (e.g., the case in L.A. but no more outbreaks since 1924).

In the last 50 years, the Plague as a biological weapon has again stimulated much interest in Yersenia Pestis. Yersenia

belongs to a family of Enterobacteriacea

and has 11 different species, of which three affect humans. Yersenia pestis

is the “Plague.” Yersenia enterocolitica

is a food-borne disease (with 50 subtypes) that emerged as a pathogen in the 1930’s. The revolution in slaughterhouses in the U.S. has changed the incidence of this disease (see Upton’s Sinclair’s The Jungle). Yersenia enterocolitis

occurs sporadically when someone eats undercooked pork. This is a diarrheal disease that goes away on its own, but may be hastened by antibiotics. As many as 117,000 people in the U.S. get this every year with about 30 deaths per year on average. Yersenia enterocolitis

is not the “Plague” (Yersenia Pestis).

Manifestations of The Plague

Bubonic: when Yersenia Pestis

bacteria get in the bloodstream, it causes swelling to the lymph nodes. The swollen lymph nodes are called “buboes,” especially in the groin or armpits. Buboes are not specific to “the Plague” (Yersenia Pestis), but can also be seen with gonorrhea and other infections of the genitalia and lymph glands. So, “Bubonic Plague” is a bit of a misnomer because the Plague bacteria could be present and kill without manifesting buboes. However, without understanding the modes of transmission and disease manifestation, previous generations have diagnosed the Plague by the presence of buboes, therefore the term “Bubonic Plague.”

Pneumonia: Airborne transmission of Yersenia Pestis

occurs. This was not known until the Plague of Los Angeles (1919-1925).

Septic: once Yersenia Pestis

gets in the bloodstream, it can cause bacteremia in which the patient becomes “septic” and dies.

Ancient Medical Ideas concerning The Plague (Black Death)

Misama

means literally “bad air.” Disease was associated with poor sanitation in urban ghettos. Unfortunately, correlation was confused with causation. The smell from decomposing matter (“miasmata”) was seen as the cause of the disease, instead of the disease causing death and decomposition, which produced foul odors. Even with backwards reasoning, there was much success in “treating” it with fresh air, the removal of corpses, and improving sewage drainage in crowded urban areas.

Working off the advances by Louis Pasteur (1860-1864), Robert Koch (1876) postulated that bacteria was the causative agent of disease, and the “germ theory” was solidified. Alexandre Yersin was a Swiss born French bacteriologist who was a student of Louis Pasteur; he discovered the bacteria Yersenia Pestis. Paul-Louis Simond discovered that the flea on the black rat was the vector of Yersenia Pestis

(the rat was not named after him).

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in the Time of The Plague

Charles de Lorme (1630) was the chief physician to Louis XIII and is credited with designing the first PPE (personal protective equipment) for “plague doctors” to do their job. The equipment included:

- A wide-brimmed hat with the brim functioning as a “shield.”

- A mask with red goggle eye-pieces and a long beak nose to store “theriac” (a composition of more than 55 herbs, including cinnamon, myrrh, honey, vinegar, spices, and dried flowers). This “covered” the smell of decomposed bodies and offered a “prevention” from the foul smells (miasma) making it to your nose.

- Goat gloves: leather protective gloves going up to the elbows.

- A long black, hooded oily coat covered in the hard white fat (suet) used for wax, puddings, and pastries. Perhaps this was to prevent blood and liquids from permeating the clothing? It was worn with leather breeches.

- A wooden cane used to prod a body to see if they were dead while maintaining about a six-foot distance (remember Monty Python’s “Bring out yer dead!”).

- I have been unsuccessful in ascertaining whether the bird-beak was strictly a functional element to allow distance for the miasmic air to be remedied by the theriac mixture or whether the bird mask held symbolic significance as it did among ancient gnostic cults? If you find this, please let me know.

A Modern Footnote

During a plague of tuberculosis, Carl Flugge developed the “droplet theory of infection” (1899). As a protective barrier for caregivers, he made “masks” from roller gauze strips. Hamilton published a paper in 1905 discussing the spread of scarlet fever by droplets. The testing of these masks continued from 1905-1920. From 1920-1940, great emphasis was placed on the “surgical mask” for operations and new materials were employed. From 1940 until 2019, the value of wearing a mask and gown in surgery has been seriously questioned with no difference in operative infection rates when masks and gowns are not worn.

COVID-19 has brought us full circle on PPE and the use of “masks.” Initially the masks were reported to be predominantly for sick patients to wear to stop droplet spread when they sneezed or coughed. Within three weeks of this pronouncement by the CDC, the advice was revised: since droplets can be “airborne” and be spread by normal close conversation, even when “pre-symptomatic,” everyone, even if presumably healthy, should therefore wear a surgical mask.

Plagues and PPE are topics that continue to spread everywhere.

Mark Mosley

has done emergency medicine at Wesley Medical Center in Wichita, Kansas for over 25 years. He is boarded in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics. He received his M.D. from the University of Oklahoma. He earned his Master’s in Public Health in nutrition from Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. He is married to his wife Jane and has five children. He attends Saint George Orthodox Christian Cathedral.