The Nature of Evil, The Fall of Adam, and the Origin of Passions

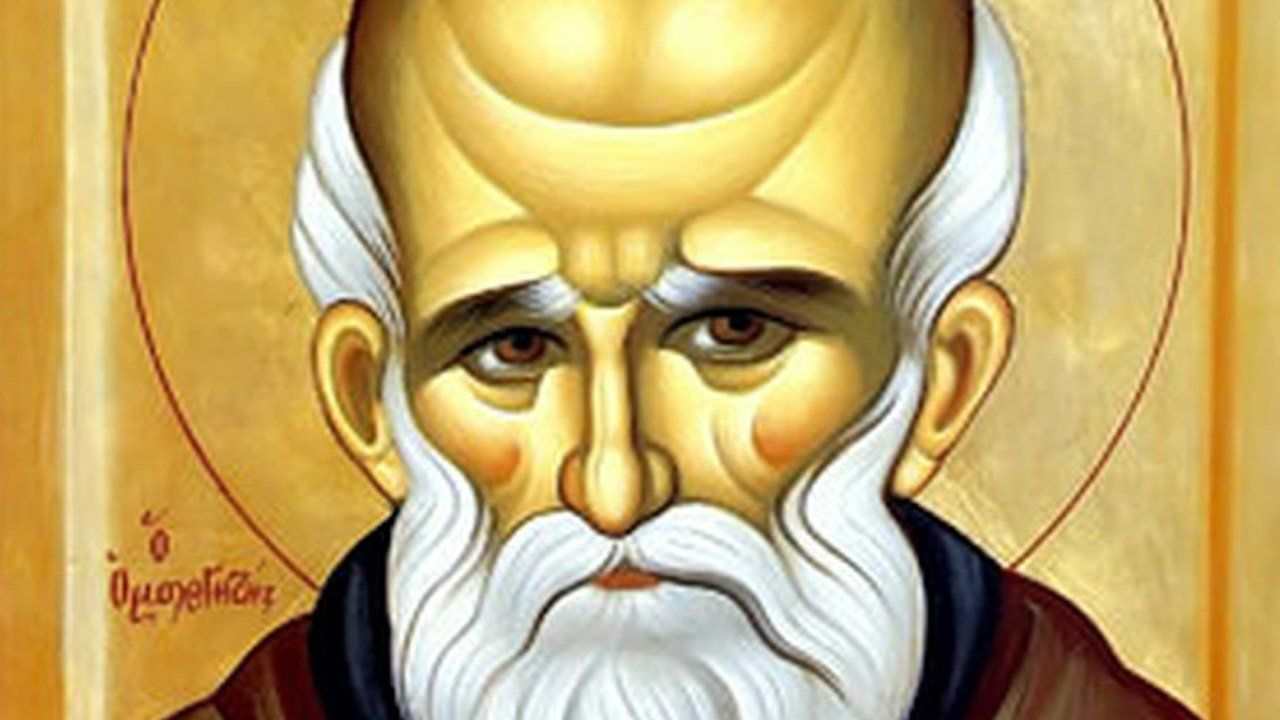

by St Maximos the Confessor

Feast of St Maximos the Confessor

Anno Domini 2023, August 13

1.2.11. Evil neither was, nor is, nor ever will be an existing entity having its own proper nature, for the simple reason that it has absolutely no substance, nature, subsistence, power, or activity of any kind whatsoever in beings. It is neither a quality, nor a quantity, nor a relation, nor place, nor position, nor activity, nor motion, nor state, nor passivity [fn. 35: With the exception of “motion,” these terms correspond to Aristotle’s celebrated rules of predication (Aristotle, Categories 1b25-2a4), …] that can be observed naturally in beings—indeed, it subsists in no way whatsoever in any beings according to their proper nature—for it is neither a beginning, nor a middle, nor an end. But so that I might speak as if encompassing it in a definition, evil is nothing other than a deficiency of the activity of innate natural powers with respect to their proper goal.

1.2.12. Or, again, evil is the irrational movement of natural powers toward something other than their proper goal, based on an erroneous judgment. By “goal” I mean the Cause of beings, which all things naturally desire [fn. 37: cf. Aristotle, Metaphysics 1.1980a …], even if the evil one—by concealing his envy behind a counterfeit kindness, and by using a ruse to persuade man to redirect his desire to something in creation instead of its Cause—has brought about ignorance of the Cause.

1.2.13. The first man, consequently, being deficient in the actual movement of his natural powers toward their goal, fell sick with ignorance of his own Cause, and, following the counsel of the serpent (Gn. 3:2-6), thought that God was the very thing of which the divine commandment had forbidden him to partake (Gn. 2:16-17) [fn. 39: In the case of Adam, the evil that is “deficiency” arose from entering into a relationship with created reality before developing the proper cognitive and moral capacity for such a relationship.]. Becoming thus a transgressor and falling into ignorance of God, he completely mixed the whole of his intellective power with the whole of sensation, and drew into himself the composite, destructive, passion-forming knowledge of sensible things [fn. 40: The fall, in addition to being a shift of human energy from a spiritual to a biological plane, also brought about the mixture and confusion of intellect and sensation, which mirrors the Christological concerns for an “unconfused union” of the divine and human natures in Christ; …]. It was thus that he was “ranked among the irrational beasts and came to resemble them” (Ps. 48:12, 20), in every possible way acting for, seeking after, and wishing for the very same things as they, and indeed surpassing them in their lack of reason by exchanging natural reason for something contrary to nature (cf. Rom. 1:23-25).

1.2.14. Thus the more that man was preoccupied with knowledge of visible things solely according to the senses, the more he bound himself to the ignorance of God; and the more he tightened the bond of his ignorance, the more he attached himself to the experience of sensual enjoyment of the material objects of knowledge in which he was indulging; and the more he took his fill of this enjoyment, the more he inflamed the passionate desire of self-love (cf. 2 Tim. 3:2) [fn. 43: In Chapters on Love 2.8, 2.59; 3.8, 3.57, Maximos defines self-love as “the passion of attachment to the body” and “mindless love for the body” …] that comes from it; and the more he deliberately pursued the passionate desire of self-love, the more he contrived multiple ways to sustain his pleasure, which is the offspring and goal of self-love. And because it is the nature of every evil to be destroyed together with the activities that brought it into being, he discovered by experience that every pleasure is inevitably succeeded by pain, and subsequently directed his whole effort toward pleasure, while doing all he could to avoid pain, fighting for the former with all his might and contending against the latter with all his zeal. He did this believing in something that was impossible, namely, that by such a strategy he could separate the one from the other, possessing self-love solely in conjunction with pleasure, without in any way experiencing pain. It seems that, being under the influence of the passions, he was ignorant of the fact that it is impossible for pleasure to exist without pain. For the sensation of pain has been mixed with pleasure even if this fact escapes the notice of those who experience it, due to the passionate domination of pleasure, since whatever dominates is of a nature always to be prominent, overshadowing the perception of what is next to it [fn. 44: Maximos’s dialectic of pleasure and pain has distant roots in Stoic psychology, but is more immediately related to Gregory of Nyssa, On Virginity 3 …].

1.2.15. Thus the great and innumerable mob of passions was introduced into human life and corrupted it. Thus our life became filled with much groaning—a life that honors the occasions of its own destruction and which, out of ignorance, invents and cherishes excuses for corruption. Thus the one human nature was cut up into myriad parts, and we who are of one and the same nature devour each other like wild animals. Pursuing pleasure out of self-love, and for the same reason being anxious to avoid pain, we contrive the birth of untold numbers of destructive passions. For example, if through pleasure we give heed to self-love, we give birth to gluttony, pride, vainglory, grandiosity, avarice, greediness, tyranny, haughtiness, arrogance, folly, rage, conceit, pomposity, contempt, insolence, effeminate behavior, frivolous speech, profligacy, licentiousness, ostentation, distraction, stupidity, indifference, derision, excessive speech, untimely speech, and everything else that belongs to their offspring. If, on the other hand, our condition of self-love is distressed by pain, then we give birth to anger, envy, hate, enmity, remembrance of past injuries, reproach, slander, oppression, sorrow, hopelessness, despair, the denial of providence, torpor, negligence, despondency, discouragement, faint-heartedness, grief out season, weeping and wailing, dejection, lamentation, envy, jealousy, spite, and whatever else is produced by our inner disposition when it is deprived of occasions for pleasure. When, as the result of certain other factors, pleasure and pain are mixed together resulting in depravity—for this is what some call the combination of the opposite elements of vice—we give birth to hypocrisy, sarcasm, deception, dissimulation, flattery, favoritism, and all the other inventions of this mixed deceitfulness [fn 47: Larchet (SC:529:138, n. 2) states that here Maximos points to three sources of the passions arising from self-love: the search for pleasure, the avoidance of pain, and the combination of these two tendencies, resulting in three categories of passions. He notes thatsuch a theory is original to Maximos and finds no equivalent in earlier patristic literature.]. But you should know that here I cannot possibly enumerate and explain all of these things in terms of their proper forms, modes, causes, and occasions. When God grants me the strength, however, I shall take up the examination of each of these in a separate discussion.

1.2.16. Even, then, as I said a moment ago, is ignorance of the benevolent Cause of beings. This ignorance, which blinds the human intellect and opens wide the doors of sensation, utterly estranged the human intellect from divine knowledge and filled it with the impassioned knowledge of objects of sense. Partaking unreservedly in the latter solely to indulge his sensations—and discovering through experience, after the manner of irrational beasts, that participation in sensible realities is what sustains the physical nature of the body, and having by this time gone far astray from intelligible beauty and the splendor of divine perfection—man unsurprisingly mistook the visible creation for God (cf. Rom. 1:20-21) and consequently made a god out of creation, since the created order had become necessary for the sustenance and survival of his body. Thus he became enamored of his own body, which was of the same nature as the creation he deemed to be God, and with all his zeal he “worshiped creation rather than the Creator” (Rom. 1:25), by cherishing and pampering the body alone. For it is not possible for someone otherwise to worship creation if he does not lavish care on the body, just as one cannot worship God if he does not purify his soul by means of the virtues. It was thus with his body that man conducted his corrupting worship of creation, and it was according to the body that he became a lover of his own self, ceaselessly engendering pleasure and pain, always eating from the Tree of Disobedience, which through experience offered to his perception the knowledge of good and evil thoroughly mixed into one (Gn. 2:17).

1.2.17. If perhaps someone were to say that the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (cf. Gn. 2:17) is the visible creation, he would not fail to hit the mark of truth, for to partake of it naturally produces pleasure and pain.

1.2.18. Or again, one could say that, insofar as the visible creation contains spiritual principles that nourish the intellect, and, at the same time, possesses the natural potential both to delight the senses and distort the intellect, it was called the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. That is, when spiritually contemplated it possesses the knowledge of the good, but when it is rejected in a corporeal manner it possesses the knowledge of evil, and to those who partake of it corporeally it becomes the teacher of passions, making them oblivious to divine realities [fn. 54: Through the contemplation of the logoi, which refer the intellect to God, creation can be seen to “possess knowledge of the good,” but when, on the other hand, through the passions, the mind attends only to creation’s superficial, sensible forms, it “possesses knowledge of evil.”]. It was perhaps for this reason that God temporarily forbade man to partake of it, rightly delaying for a while his participation in it, so that, through participation in grace, man might first know the. Cause of his own being, and afterwards, by partaking of grace, add impassibility and immutability to the immortality given to him by grace. Having in this way already become God through divinization, man might have been able without fear of harm to examine with God the creations of God, and to acquire knowledge of them, not as man but as God [fn. 55: Cf. Ambigua to John and Thomas 10.60: “Adam, by means of sense perception, sought to make his own (as one must not) the things of God without God, and before God, and not according to God, which is in any case impossible.”], having by grace the very same wise and informed knowledge of beings that God has, on account of the divinizing transformation of his intellect and powers of perception [fn. 56: Divinization does not exclude knowledge of creation, but through God it is known dispassionately, and indeed in the very manner that God knows it, which is to say from the perspective of the logoi, which are God’s eternal intentions for created beings; cf. Amb. 7.24: “God neither knows sensory things by sensation, nor intelligible things by intellection … but <knows them> as His own wills.”]

1.2.19. Whereas this anagogical interpretation concerning the tree is suitable for everyone, it should be understood that the more mystical and superior sense is reserved for the understanding of mystics, and is honored by us through silence. As for the Tree of Disobedience, I have referred to it now only in passing, wishing to show that ignorance of God made a god out of creation, the worship of which is the self-love that human beings have for their own bodies. It is with respect to this self-love that the experience of pleasure and pain is a kind of mixed knowledge, through which all the impurity of evil was introduced into human life in many different ways and in manifold forms, which no discourse could encompass, since all who share in human nature possess, according to varying degrees of quantity and quality, a vital and active affection for the visible part of that nature, by which I mean the body. Moreover, this affection forces man, as if he were a slave, to contrive all kinds of passions in his desire for pleasure and fear of pain—relative to the times and circumstances, and as his manner of life allows—with the aim of enjoying pleasure in every aspect of his life while avoiding all possible contact with pain [fn. 58: The perceived good for the body is the sensation of pleasure, while its perceived opposite, pain, is taken to be evil. This reductive and distorted scale of values is sustained by the sensible world, apprehending in separation from God, without whom it becomes like a tree bearing false good and evil. The mind can either know creation on the level of its logoi or through sensation can attach itself passionately to the outward appearances of things for the purposes of sensory pleasure.]. This affection for the body teaches us to undertake something that can never be accomplished or ever reach the limit it has set for itself. Insofar as the entire nature of physical bodies is corruptible and subject to dissolution, whatever a person does to keep it in a condition of stability, he succeeds only in hastening the body’s corruptibility, for out of fear he does not always wish for the object of his desire, but instead, contrary to all sense and his own free will, he pursues what is not desirable through what is desirable, having become dependent on things that by nature can never be stable. He is consequently subject to change together with those things that break up and scatter the disposition of his soul, which is ceaselessly tossed about like a ship on a sea of perpetual flux and change, while he himself fails to perceive his own destruction, for the simple reason that his soul is completely blind to the truth.

1.2.20. Deliverance from all these evils and the shortest way to salvation, is the true and conscious love of God, along with the total denial of the soul’s affection for the body and this world. Through this denial, we cast off the desire for pleasure and the fear of pain, and being freed from evil self-love we are raised up to knowledge of the Creator. In place of evil self-love, we receive good, intellective self-love, which is utterly separated from affection for the body, and through it we never cease to worship God, ever seeking from Him the sustenance of our soul, because true worship that is pleasing to God is the care of the soul by means of the virtues (cf. Jn. 4:23).

1.2.21. Thus whoever does not desire bodily pleasure and has absolutely no fear at all of pain has become dispassionate with respect to them, and with one accord has put to death all the passions, the self-love that gives birth to pleasure and pain, and all the passions that result from them, as well as ignorance, which is their primary cause. Such a person comes to be wholly under the rule of what is naturally good and beautiful, which is stable, permanent, and always the same, so that he remains uninterruptedly with the good in a state of motionlessness [fn. 61: “Motionlessness” simultaneously denotes fixity in the good and the cessation of motion on the part of the creature that has reached its end in God; …]. , and “with unveiled face reflects the glory of God” (2 Cor. 3:18), beholding the divine and unapproachable glory from the radiant splendor shining within himself.

1.2.22. Since reason has shown us the right and easy way (cf. Jn. 14:6), which is followed by those who are being saved, let us deny, as much as we can, the pleasures and pains of this present life, and, with much supplication, let us teach those in our care to do the same, and thus we will be freed, and will free them, from every idea of the passions and from every demonic wickedness. Let our sole aspiration be divine love, and nothing will be able “to separate us from God: neither tribulation, nor distress, nor famine, nor peril, nor sword,” nor anything else mentioned by the holy Apostle in that passage (cf. Rom. 8:35), for through knowledge realized in action, this love will remain within us immutably, and God will grant us eternal, ineffable joy and sustenance of soul. And when we are deemed worthy of this love, we shall acquire an ignorance that preserves us from this world, no longer seeing the world with a carnal mind, as we once did, when the “face” of our senses was “uncovered” (cf. 2 Cor. 3:18. Fn. 65: The “uncovered face of the senses” is the impassioned fascination with the sensible aspect of the world and its surface phenomena. This “uncovering” of sense perception is simultaneously the “covering” or “veiling” of the intellect. Conversely, the more the “face” of the senses is veiled, the more the sensory veils are lifted from creation, enabling the intellect to grasp its inner meaning and purpose.], and we mistook the superficial manifestation of sensible things as “glory,” when in reality it was the source of the passions [fn. 66: This “preserving” or “saving” ignorance is not the “knowing beyond knowing” that pertains to God, but is rather that mode of the intellect that no longer misapprehends creation through the passions, no longer being fixated on isolated sensations and surface phenomena, thereby allowing creation to become fully transparent to the divine glory; cf. Amb. 10.52, where, like Moses, the purified consciousness “will be made worthy to see and hear the ineffable and supernatural divine fire that exists, as if in a burning bush, within the essence of things.”]. Instead, with the “uncovered face” of the mind, freed from every covering of sensation, we will “reflect,” through our virtues and spiritual knowledge, the “glory of. God” (2 Cor. 3:18), through which naturally comes about our union with God by grace, raising the intellect far beyond all ignorance and stumbling. For in the same way that, being ignorant of God, we deified creation (which we came to know through the sensory enjoyment of sustaining the body from it), so too, having received the knowledge of God that is actually accessible to thought—since it is from Him that our soul derives its sustenance to exist, to exist well, and to exist eternally [fn. 68: The triad of “being,” well-being, and eternal well-being,” which structures the nature of human existence and experience, is an essential feature of Maximos’s thought, and receives its fullest expression in Amb. 65.2-3.]—let us be ignorant of every experience and sensation.

*St Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in Sacred Scripture: The Responses to Thalassios, The Fathers of the Church vol. 136, trans. Fr. Maximos Constas (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2018), pp. 81-91. Available for purchase at Eighth Day Books.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.