I HAVE

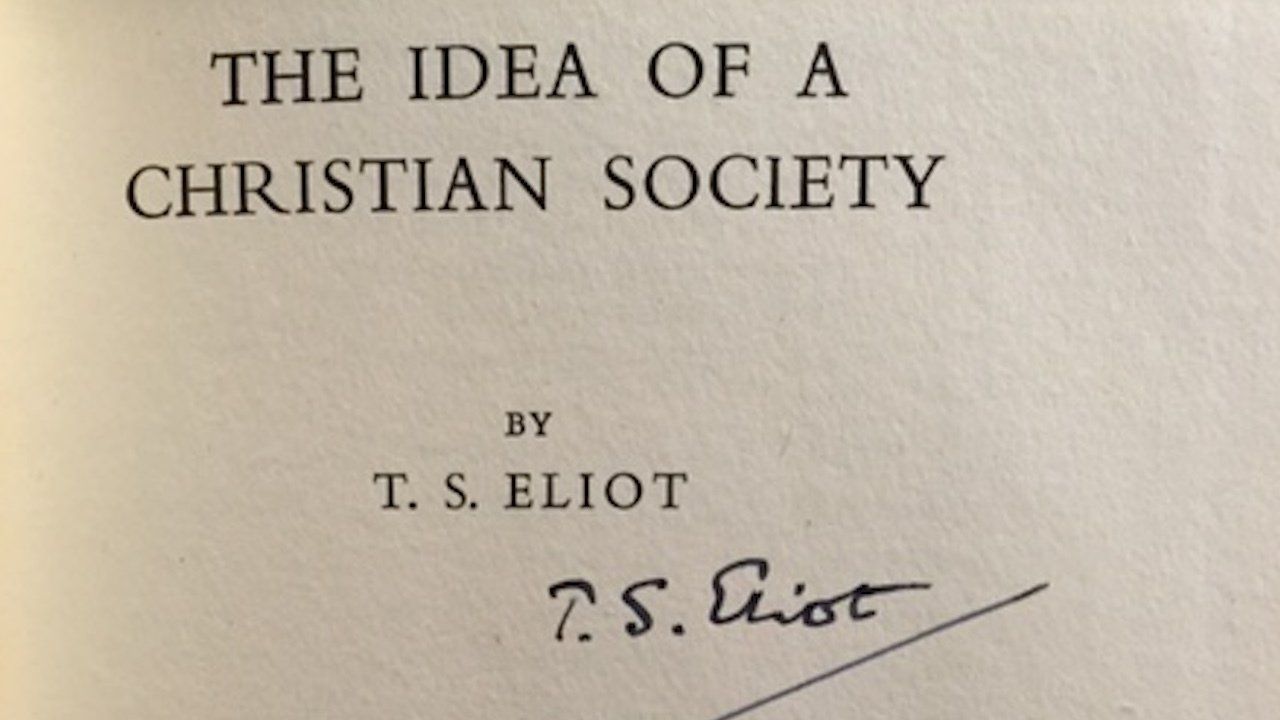

been waiting for some time to draw attention to Mr. T. S. Eliot’s book,

The Idea of a Christian Society, published last autumn. Many readers of the News-Letter will already have read it for themselves. But what it contains is so relevant to the central interest of the News-Letter that it ought to be brought to the notice of those who have not.

The importance of this slim volume bearing this title is out of all proportion to its size. In less than a hundred pages, only two-thirds of which are occupied with the main text, Mr. T. S. Eliot has given us a work of unusual originality and power. It has already had the rare effect of giving a perceptible direction to Christian thought. No one can in the future discuss the question of a more Christian order of society without taking account of what Mr. Eliot has said.

This is due, at least in part, to his care and exactness in the use of terms. He modestly disclaims the qualification of profound scholarship; but suggests, very rightly, that it may be some compensation that the practice of poetry trains the mind in the valuable habit of analyzing the meaning of words. So thick a fog of vagueness and sentiment envelops much of the talk about a Christian society that we cannot be too grateful for Mr. Eliot’s clear distinctions and precise and measured statements.

The Urgency of the Issue

The book is not addressed to everyone. There is one class of person to whom Mr. Eliot knows that he speaks in vain. It is, unfortunately, a very large class, and one into which all of us through natural sloth at times fall. It is the class of those who cannot believe that things will ever be very different from what they are at the moment.

The prevalence of this state of mind makes one wonder whether we must wait for destruction from the air or a complete economic upheaval to arouse us from our complacency. One of the lessons which Professor Arnold Toynbee draws from his survey of the history of civilizations is that no more than an individual can a nation or civilization afford to rest on its oars. Life is a continuous adaptation to environment, and a people’s greatest and proudest achievements may in a changed environment become their prison or their grave. Only a fresh response to every new challenge can save a civilization from breakdown.

It needs an attentive reader to perceive beneath the terse, restrained exposition the writer’s ever-present sense of the urgency of the questions with which he is dealing. It was not an academic interest that prompted the writing of the book. Mr. Eliot was moved to undertake it by a profound shock to his moral nature in September, 1938. There was raised in his mind a fundamental doubt about the soundness of our present civilization. Was this society, so confident of itself and its achievements , living in fact by any beliefs more essential than a belief in compound interest and the maintenance of dividends?

Is Our Society Christian or Pagan?

There have come into existence in what was once known as Christendom new pagan societies. It may be questioned whether “pagan” is the right designation for societies that have once known, and have consciously rejected, the Christian faith. But for our present purpose the term may pass. What of our own society in this country? Has it also become pagan? To describe ourselves as a Christian society in contrast with Russia or Germany is, in Mr. Eliot’s view, an abuse of terms. It conceals the real values by which we live. Our aims, no less than those of other countries, are materialistic.

But the people in this country have certainly not yet deliberately repudiated the Christian tradition, and it may be held that a society has not ceased to be Christian until it has become positively something else. What we have at present is a culture that is mainly negative, though so far as it is positive it is still Christian. When Mr. Eliot speaks of the “idea” of a society, he means its ultimate aim. It would be difficult to say of our present society that it has any clearly conceived aim. Owing to this negative condition we have no commanding ideas, Mr. Eliot perceived, to oppose to the positive pagan systems which confronted us. We could not match conviction with conviction.

The Necessity of Choice

It is clear, moreover, that to remain in this neutral condition is impossible. We must move towards the formation of a new Christian culture or accept a pagan one. Either decision will involve radical changes. The cost of achieving a Christian society is too high to make the undertaking attractive to many. Mr. Eliot doubts whether any scheme for change can be made palatable until things have become desperate. The effort of creating a Christian society will certainly involve discipline, inconvenience, and discomfort. But purgatory is preferable to hell. If men had the imagination to foresee the consequences of the choice, the majority might prefer Christianity.

The choice has got to be made. We are coming to see with growing clearness how difficult it is to live a Christian life in a non-Christian society – even in our present society which has not yet finally made up its mind. We are entangled in a network of institutions, and if these operate in an un-Christian way we are implicated against our will. Under this continuous pressure we are being de-Christianized more rapidly than we are aware.

What Is a Christian Society?

This clearly is the crucial question. MR. Eliot’s answer is not very full or explicit but his intention is, I think, plain. He does not mean a society in which the term Christian is used vaguely and loosely to describe any behavior that conforms to general standards of decency; nor one in which the attempt is made occasionally in moments of emergency to apply Christian principles to particular political situations. Nor, again, does the name imply that the society is composed wholly, or even mainly, of devout Christians; that is not something that history and experience give us any ground for expecting.

A Christian society, moreover, cannot be created by the methods of emotional revivalism. The effect of a campaign for moral re-armament in a secularized society can only be to strengthen secular values. It is not enthusiasm but dogma that differentiates a Christian from a pagan society. That is Mr. Eliot’s clear-cut answer to much loose talk that is common today.

He does not, I take it, mean to decry enthusiasm. He would not quarrel with Sir John Seeley’s contention that all other faults or deficiencies Christ could tolerate, but he could have neither part nor lot with men destitute of enthusiasm; nor with Edmund Burke’s reminder that strong passions awaken the faculties, inasmuch as they suffer not a particle of the man to be lost. What Mr. Eliot asserts is that enthusiasm can do little good, and may do much harm, unless it is evoked by, and directed to, the right object. The reference to dogma I take to mean that a Christian society is one which orders its affairs in the light of an understanding of man and of a scale of values derived from central Christian beliefs.

It is not part of Mr. Eliot’s purpose to consider the changes in industry and social institutions which the acceptance of the Christian view of life would bring about. But he is certain that its acceptance would involve radical changed in these spheres, and he would regard such reform as the test of the extent to which a society could justly be described as Christian. A Christian society, he says in another place, would be one in which the natural end of man – virtue and well-being in community – is acknowledged for all, and the supernatural end for all who have eyes to see it.

The meaning will become clearer if we consider the three elements of a Christian society which Mr. Eliot calls the Christian State, the Christian Community, and the Community of Christians.

The Christian State

The Christian State is the Christian society under the aspect of legislation, public administration, legal tradition, and form. It is not tied to any particular form of government, but may assume any form that is suitable to a Christian society. It is not implied in a Christian State that the rulers are chosen because of their qualifications as Christians. The matter of central importance is not their personal adhesion to Christianity but the fact that they would be expected to act within a framework of Christian principles. They would have received a Christian education, through which they would have learned to think in Christian categories, and know the standards to which they were expected by the temper and traditions of the people to conform. They might often commit un-Christian acts, but they would not be allowed to defend their actions on un-Christian principles. A society is better served by a skeptical or indifferent statesman working within a Christian frame than by a devout statesman who is compelled to conform to a secular frame.

The Christian Community

For the great majority of the members of the Christian society which Mr. Eliot has in view religion would be largely a matter of behavior and habit. Both their religious observances and their social conduct would be determined in the main by custom and tradition rather than by a conscious faith. The way of life to which they were expected to conform, that is to say, would be one that was in harmony with the Christian understanding of the ends of life and a Christian order of values.

It is to this point in the presentation that criticism has been chiefly directed. It is suggested that Mr. Eliot ignores the need for conversion, and that his Christian society fails to embody the uncompromising demands which Christianity must always make if it is to remain true to itself.

This charge, however, would seem to be based on a misunderstanding. Mr. Eliot is not at this point speaking about the Church or about those who accept the full obligations of membership of the Church. He is speaking of society as a whole, and the question to which he seeks an answer is what is the minimum requirement that would justify us in calling a society Christian. He accepts the fact of experience that the majority of men in any society are largely governed by custom and that those who live a conscious Christian life are a small minority; and he maintains that, in spite of this, a society might properly be called Christian if it contains as a leaven a body of convinced and committed Christians, and if this leaven has so far penetrated its life in such a way that what is ordinarily expected from people accords in a broad sense with Christian standards.

The difficulty might perhaps not have arisen if Mr. Eliot had followed a different order and dealt with the Church and the Community of Christians before describing the Christian Community; but his subject, after all, was the idea of a Christian society.

He recognizes that if there is to be a Christian society at all, the great mass of humanity must in some sense become adapted to it, and that in this process Christianity will inevitably have also become adapted to the mass. A society in which all professed Christians might consequently be a society on a low level. But against this danger there is, and can be, no protection except the vigor of the Christian life. If the salt has lost its savor, wherewith can it be salted?

The Community of Christians

Herein lies the importance of the third essential element in a Christian society, which Mr. Eliot calls the Community of Christians. This is not the same as the membership of the Church. What Mr. Eliot is seeking for is some term to describe that element among Christians which operates as a creative and educative force in society. His Community of Christians is a body, somewhat indistinct in its boundaries, of conscious, thoughtful, and practicing Christians, possessing spiritual and intellectual gifts beyond the ordinary, which enable them to exert a formative influence on social life. It would include both clergy and laity, and its function would be through its spiritual and intellectual grasp of Christian truth to leaven the life of society with Christian ideas and values.

The Church

None of the three elements that have been mentioned is identical with the Church. There cannot be a Christian society without a Church, which is at one and the same time national, in the sense that it aims

at comprehending the whole nation, and also part of the universal Church. The dual loyalty to the nation and to the universal Church creates a tension, but this tension is essential to the idea of a Christian society. The Church will be the final authority within the nation in all matters of faith and morals.

The Church would have relations to each of the three elements already considered. Through its official leaders it would have relations with the State. It might at times be in conflict with the State. It would be its duty to protest, when the need arises, against un-Christian policies or immoral legislation or the infringement of spiritual liberty.

Through its parochial and other organizations it would be in contact with the smallest units and individual members of the Christian Community. And through its scholars and intellectual leaders it would have close links with the Community of Christians.

Education

A Christian society requires a system of education in harmony with its ultimate aim. A nation’s system of education is much more important than its system of government. Education in the sense here intended, means, of course, much more than the acquisition of information and technical competence. It must impart a coherent view of life. It presupposes that is to say, a social philosophy – a definite doctrine of man and of society. This does not mean that the members of the teaching profession, any more than the rulers of the State, must necessarily be professing Christians. It means that they will work within an educational system that has been formed in accordance with Christian presuppositions regarding the ends of life.

*Published as Supplement 18 in the Christian News-Letter on February 28, 1940