WE SHOULD

never fail to remember that Christianity is a Faith with its roots in western Asia, and only slowly over the course of five centuries did it firmly establish itself on the three continents of Asia, Africa and Europe. This is necessary to keep in mind for two reasons.

First, for the humbling of our pride. Those of us in the European West should remember that Christianity is not ours to individually interpret or to preserve, though Christ may (and does) share this task with us. Christianity came to us not only from another place, but from another time and another way of thinking. We should continually look to this origin for instruction and inspiration.

This speaks to the second reason we should remember those first centuries of the Church. Not only the circumstance but the means of the Church’s birth should be a source of contemplation. Faith in Jesus was not spread and rooted in the world by war and violence, by logic and scholarship, or by adherence to moral systems.

The Church was born in Holiness.

In and through the holy lives and witness of the early apostles, martyrs and confessors was Christianity indelibly impressed on history. Holiness is true war, reason, and morality. And the early Christians “fought” by prayer, service, and martyrdom.

When we compare the lives of the apostles and martyrs with the many trends and movements in the Faith down the centuries, we have cause to be alarmed and ashamed. Some have tried to persuade through superior military might. In this regard, the Crusades and the age of colonization come to mind, when conversions were forced through violence, threat, bribery.

Some have tried to spread the faith through fear of punishment - either temporal or eternal. There are many social groups and philosophies which claim to speak for Christianity, but offer in its place only a more or less strict, more or less complex social code. Heaven is assured to those who “follow the rules” and behave correctly; Hell awaits those whose activities are substandard.

Some have tried to spread the faith through programs of education and indoctrination. Rhetorically beautiful philosophical systems replace the Gospel, and are often so alluring in their literary power that the substitution goes on, unnoticed, for centuries. In this case, the most well-researched and thoroughly-footnoted theology is considered the most correct.

In all these methods, of course, we may find seeds of good intention. We do not, of course, wish to live contrary to reason, and we do strive to “work out our salvation with fear and trembling.” But taken to extremes in isolation, social programs and evangelistic methods become dangerous and directly counter to the message of Jesus who came “not to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through Him.”

Some of our traditions have reached a point in which they cannot conceive of the Faith except through the lens of some belief that is tangential, external or even contrary to the Gospel. Several examples immediately come to mind.

Perhaps we believe that the essence of Christianity is well-performed, beautiful liturgies. Or that the essence is “tolerance” of all people at all times. We frequently insist that the essence is a rather superficial membership in one communion over or against another. Many are taught that real Christianity is foreign missions, and anything less is a kind of spiritual failure.

We are not questioning the importance or value of these beliefs. In fact, they are good in their place. We are, instead, looking for essence

and comparing all else to this essence, which is Holiness. When Holiness is forgotten or lost, the good is mistaken for the best. And the good-but-not-essential aspects of our traditions can subtly become excuses for our choosing not to pursue a deeper union with God. We might say, “I am a member; that is all I need to do;” “I am kind and generous; that is all I need to do;” “My church has beautiful services.” These less important things are tempting because they are easily made into measurable goals. We want to see our progress, and compare ourselves to others.

Holiness, however, is not easily measured or attained. Our scriptures are expressly clear on this point: “Through many trials we must inherit the Kingdom of God.” “They will deliver you over to affliction and kill you.” “Strive to enter by the narrow door.”

The heroes of the Church in its first five centuries did the difficult and Christ-inspired work of attaining holiness. They taught doctrines from holiness; they stood before judges and executioners in holiness; they went out to the deserts to pray in holiness. They were filled by the Holy Spirit.

And we might pause here to ask, why does the Church give this third Person of the Trinity the appellation “Holy?” Why not Divine, Beautiful, Powerful, or Loving - which are also attributes of God? This alone should impress on us the importance of holiness, and lead us to ask: what does it mean to be holy?

Without definitions and descriptions of holiness frequently set in front of us, we are each confined to our own ideas of this word, and perhaps to self-justifications based on these ideas. Remembering that holiness is ultimately beyond what we can express, we might for the sake of these reflections consider two possible descriptions - one brief, and one more extensive.

Briefly, the word holy refers to that which has been fully consecrated to God. Consecration is mysterious and profound. Even for the consecration of objects for holy use, there are prayers and observances, and not every object is sought out for consecration. The creation of the world is depicted in Genesis 1 as a series of consecrations. When fallen human beings are called to return to holiness, how much more awe-inspiring and difficult.

Jesus spent three years intimately consecrating His disciples. Saint Paul went into the desert and then carefully consulted with the early Christians to be certain his teaching was holy. Seminaries, monastic orders, eldership, ordinations - these all speak to the care our communities take to ensure that holiness is recognized and preserved for the very consequential offices of Church leadership.

We mention this short definition first, because holiness, being something divine (and therefore both natural and supernatural) should be described as both simple and complex, both given and struggled for, both easy and difficult, both immediate and subsequent. Many of our arguments about holiness through the centuries ensue because we do not keep the full mystery and richness of holiness in mind.

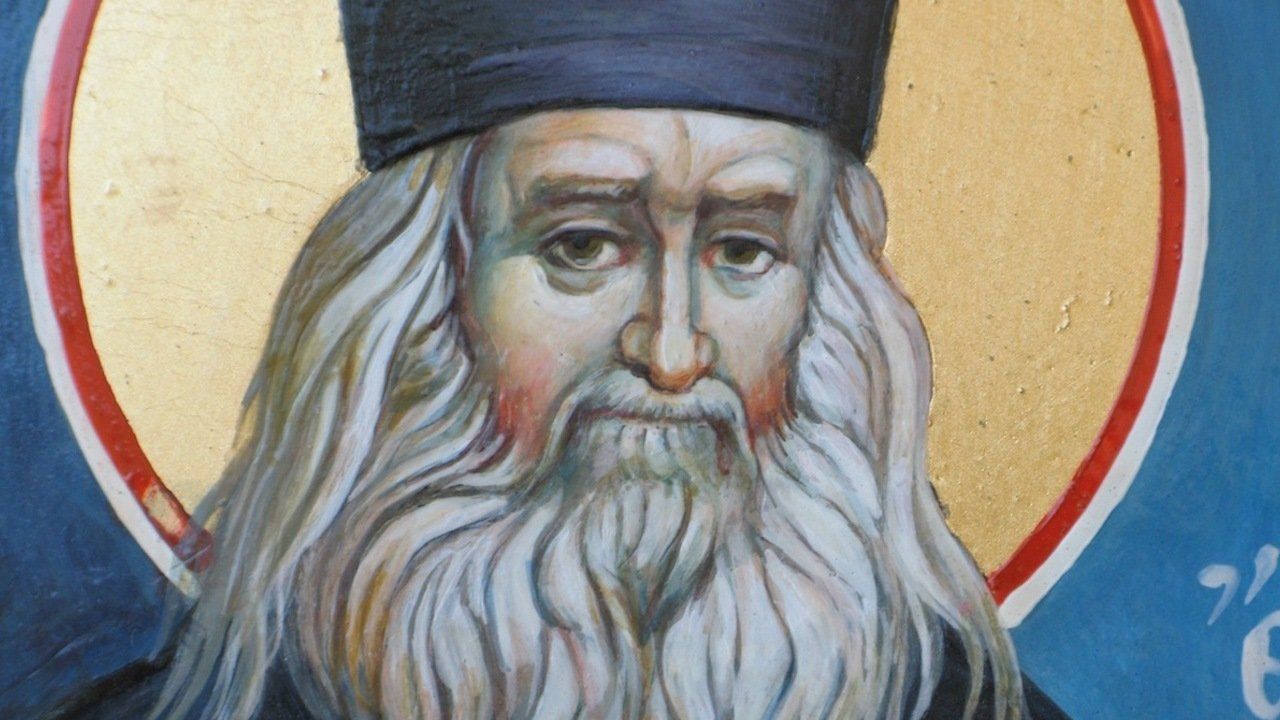

The short definition is helpful, but does not offer us a direction or compass. Many would like to pursue a more deep union and consecration to God, but do not know how to start or how to maintain. So we might look for something more concrete - a measure or description offered by a member of the Church who has lived a holy life. There are many such people. We call them variously Saints, Elders, Sages, Teachers, and all traditions preserve their example.

*This is the first half of an essay which will appear in its entirety in Synaxis 7.1 for the tenth annual Eighth Day Symposium.