The Authority of the Ancient Councils and the Tradition of the Fathers - Part I

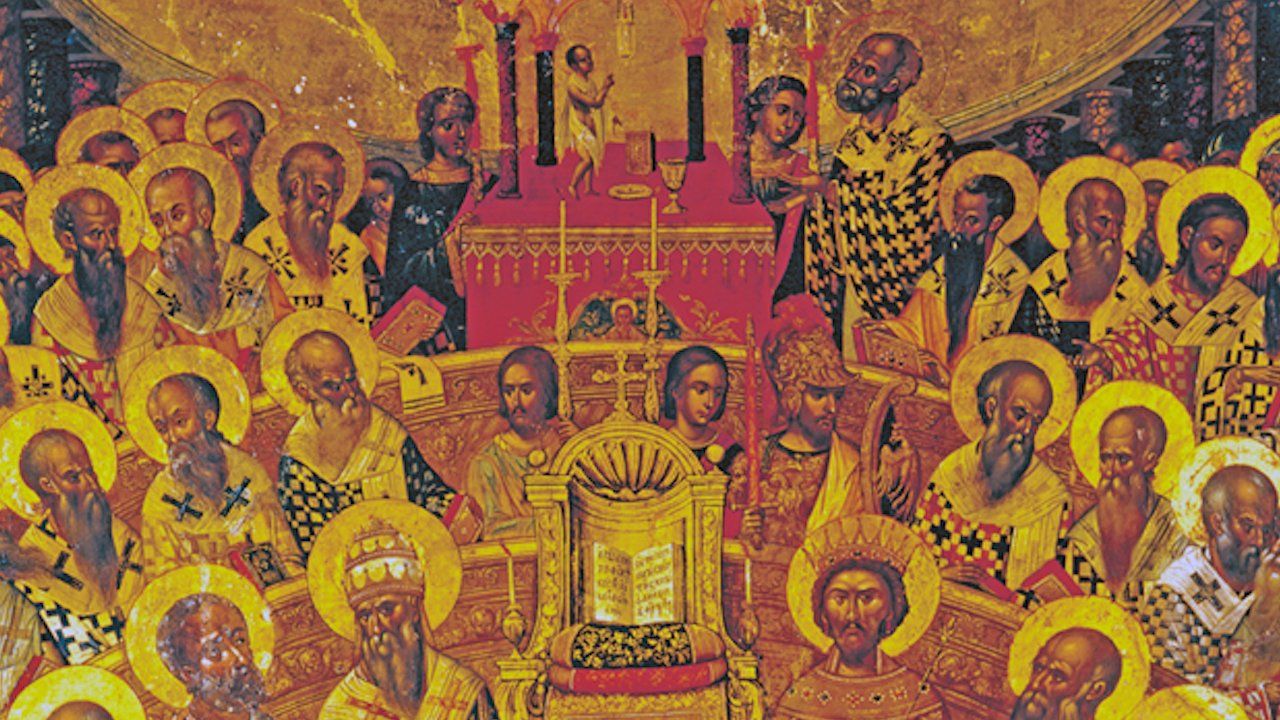

The Councils in the Early Church

THE SCOPE of this essay is limited and restricted. It is no more than an introduction. Both subjects—the role of the Councils in the history of the Church and the function of Tradition—have been intensively studied in recent years. The purpose of the present essay is to offer some suggestions which may prove helpful in the further scrutiny of documentary evidence and in its theological assessment and interpretation. Indeed, the ultimate problem is ecclesiological. The Church historian is inevitably also a theologian. He is bound to bring in his personal opinions and commitments. On the other hand, it is imperative that theologians also should be aware of that wide historical perspective in which matters of faith and doctrine have been continuously discussed and comprehended. Anachronistic language must be carefully avoided. Each age must be discussed on its own terms.

The student of the Ancient Church must begin with the study of particular Councils, taken in their concrete historical setting, against their specific existential background, without attempting any overarching definition in advance. Indeed, it is precisely what historians are doing. There was no “Conciliar theory” in the Ancient Church, no elaborate “theology of the Councils,” and even no fixed canonical regulations. The Councils of the Early Church, in the first three centuries, were occasional meetings, convened for special purposes, usually in the situation of urgency, to discuss particular items of common concern. They were events , rather than an institution. Or, to use the phrase of the late Dom Gregory Dix, “in the pre-Nicene times Councils were an occasional device, with no certain place in the scheme of Church government” (“Jurisdiction, Episcopal and Papal, in the Early Church,” Laudate , XVI [No. 62, June 1938], 108). Of course, it was commonly assumed and agreed, already at that time, that meeting and consultation of bishops, representing or rather personifying their respective local churches or “communities,” was a proper and normal method to manifest and to achieve the unity and consent in matters of faith and discipline. The sense of the Unity of the Church was strong in Early times, although it had not yet been reflected on the organizational level. The “collegiality” of the bishops was assumed in principle and the concept of the Episcopatus unus was already in the process of formation. Bishops of a particular area used to meet for the election and consecration of new bishops. Foundations had been laid for the future Provincial or Metropolitan system. But all this was rather a spontaneous movement. It seems that “Councils” came into existence first in Asia Minor, by the end of the second century, in the period of intensive defense against the spread of the “New Prophecy,” that is, of the Montanist enthusiastic explosion. In this situation it was but natural that the main emphasis should be put on “Apostolic Tradition,” of which bishops were guardians and witnesses in their respective paroikiai . It was in North Africa that a kind of Conciliar system was established in the third century. It was found that the Councils were the best device for witnessing, articulating, and proclaiming the common mind of the Church and the accord and unanimity of local churches. Professor Georg Kretschmar has rightly said, in his recent study on the Councils of the Ancient Church, that the basic concern of the Early Councils was precisely with the Unity of the Church: “Schon von ihrem Ursprung her ist ihr eigentliches Thema aber das Ringen um die rechte, geistliche Einheit der Kirche Gottes” (“Die Konzile der Alten Kirche,” in: Die ökumenischen Konzile der Christenheit , hg. v. H. J. Margull, Stuttgart [1961], p. 1; English translation: “From its very beginning, her major theme is the struggle for the correct, spiritual unity of the Church of God.”). Yet, this Unity was based on the identity of Tradition and the unanimity in faith, rather than on any institutional pattern.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.