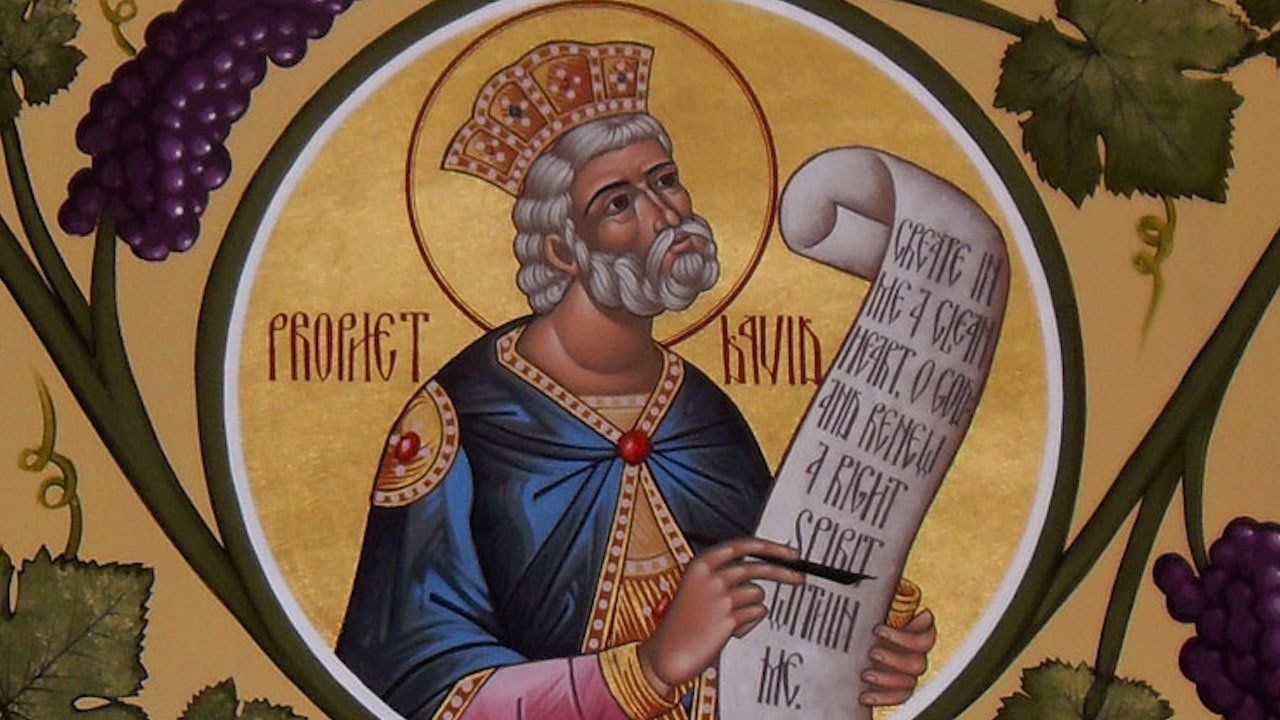

KING DAVID & HUMILITY

The background to Psalm 51 (Psalm 50, LXX) is Samuel 12:1-15 in which the reader hears the story of King David’s adultery and the murder he committed to hide it. We also learn of the death of his first male heir son from this illegitimate act. This personal emotional wound for King David and his dynasty must have been deeply grievous, a daily ache. This “sting” was com-pounded by being fully known among the Kingdom. There was no hiding of Bathsheba’s pregnancy, her husband’s untimely death, the promise of the next heir to the throne, and his first son’s death. One would not need an iPhone for this information to “go viral.”

King David joins a group of God’s chosen who are naked and ashamed before God in their sin. Isaiah the prophet says, “Woe is me, for I am doomed with sin, because I am a man of unclean lips…” (Is 6:5). Job must be literally naked before God for him to admit, “But now my eye sees You. Therefore, I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6).

King David’s penitential psalm begins with the plea, “Have mercy upon me, O God” (v.1). He later confesses, “my sin is always before me” (v.5). We will see this same heartfelt confession-al plea in the New Testament. The prodigal son, who “comes to himself” in the mud with pigs, says to his father, “I have sinned against heaven and in your sight, and am no longer worthy to be called your son” (Lk. 15:21). The publican tax collector cries out, “God have mercy on me a sinner” ( Lk. 18:13). The thief on the cross laments out loud, “we deserve this … remember me O LORD in thy kingdom…” (Lk. 23:39-43). Psalm 51 begins with King David’s sacrifice of his own pride by laying open his broken heart in confession.

SACRIFICIAL ACT OF BURNT OFFERING

David desires recompense for his guilt but appears conflicted on how to find it. He says to God, “You do not desire sacrifice or else I would give it. You do not delight in burnt offering” (v. 16). A few verses later, however, he says, “Then, you will be pleased with the sacrifices of righteousness, with burnt offerings, and whole burnt offering. Then

they shall offer bulls on Your altar” (v. 21).

Is David contradicting himself? He first says God does not desire the sacrificial act of burnt offering. But then he says God is pleased with the sacrificial act of burnt offering. Which is it? What is David saying about the act of sacrifice?

Maybe the public

act of sacrifice requires first the proper private

preparation of the heart. David cannot offer up prayers for the sins of the people until he acknowledges his own transgressions (v.3) and keeps his sins always before him (v.4). King David cannot rule over others and sit as judge without going through his own judgement. Taking the lid off of our own sin and air-ing out its stench brings air to a fire that purifies the environment. God is not

against a sacrifice; He is against the pride of a sacrifice which snuffs out the flame of the Holy Spirit. “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, a broken and contrite heart God will not despise” (v.7). A bro-ken heart is the clean and washed altar where the Holy Spirit catches fire. The burnt offering of sacrifice is not desired by God until it is fueled with humility, then God will be pleased with the sacrifice. Knowing who you are before God comes before knowing who you are in the community.

THE “LETTING GO” OF SACRIFICE

The sacrificial animal was unblemished. It was the prized animal of the entire herd. It may have represented the future security of a well-bred stock. It may have been the financial security of food, milk, meat, and clothing for a hard season ahead. The prized animal was more than the pride or ownership of a great possession. Anyone who has lived in a pastoral setting, or owned a pet, knows the comfort a domesticated animal brings. They have names. You look for them and they look for you to know everything is OK. You guard them, and they are loyal and never judge you. To give up this animal, your most prized animal, to God and others would be an unimaginable struggle. There would be a natural temptation to hold on to the “sacred cow.” As in the story of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5), you are tempted to hold back the best portion for yourself and sacrifice something “second-best” for the community. Or there would be a natural temptation after sacrificing your “unblemished lamb” to make sure others were aware of your sacrifice—of “everything you had done for this Church” (and what they all owed you for your sacrificial gift).

The same can be said of David’s sin. And the same can be said of ours. We have sins that are “sacred cows.” We live with the animal nature of our sin and “domesticate it” because it does bring us a sense of well-being in our pride, comfort, security, and pleasure—even knowing it will be short-lived, or even completely false. And we also “hide” our most treasured animal instincts; we “hold back” “what we own” from the community. Our confession holds on to the secret domestic sin.

“Owning up to your sin” is the first part of a good sacrifice. But the shame and self-condemnation can be a black smoke as suffocating as the sin itself. “Holding on” to the judgment of yourself after the sacrifice is just as despised as the sin. To continue in the guilt after confession and after an offering to God, makes God’s offering ineffectual if not offensive. Your broken heart has been kept for yourself. You would rather have the autonomy of “beating yourself up” in shame than risk the uncertainty of divine freedom.

The whole burnt offering is not just the killing of an animal. It is “letting it go” to be wholly consumed into a fragrant smoke that rises into the heavens. I lower myself into “dust and ash-es” as a preparation to “lift up my head” “with a clean heart.” My “bones are broken” in order that I may “walk through the valley of the shadow of death and fear no evil.” “My sin is ever be-fore me” so that God does not allow my hidden sin to define me. The “letting go” of what you own, your sin and your shame, is the summit of the sacrifice.

THE PREPARATION OF THE EUCHARIST

In the Orthodox Christian liturgy, before the priest enters into the altar with the Holy gifts, he prepares himself first and then the entire community. He does this by reciting this Psalm 51 in its entirety. He prays

Have mercy upon me O God, according to Thy great mercy; and according to the multitude of Thy mercies blot out my transgression. Wash me thoroughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I know mine iniquity, and my sin is ever before me….

There is no “we” in this request. The priest is praying the words of an adulterer, a murderer, a prodigal, a tax-collector, and a thief. You see the Light of God only after seeing the darkness of yourself. Repentance is the path to Theophany. The priest prays psalm 51 to himself every liturgy while he censes the people and the house of God. He continues,

Turn Thy face away from my sins, and blot out all mine iniquities. Create in me a clean heart O God and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from Thy presence, and take not Thy Holy Spirit from me…

This is the preparation for the “Great Entrance” into the Holy of Holies where the sacrifice (eucharist) of God is offered:

the LORD (is) sitting on a throne, high and lifted up, and the train of His robe filled the temple. Above Him stood the seraphim. Each had six wings: with two He covered His face, and with two He covered His feet, and with two He flew. And one called to an-other and said “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts; the whole earth is full of His glory.” (Isaiah 6:1-3)

The priest and now each member of the community is to see their own heart unveiled and naked before God. Then by grace, the self is turned around so that it may be washed and cleaned. We empty ourselves, and “lay aside all earthly care.” The face of our sins are covered completely by the chalice of Christ. We ascend and surround the throne as “we who mystically represent the Cherubim sing Holy, holy, holy.” The burnt offering is ourselves. We ascend to the Seraphim in order that we may be “ones on fire.” The Holy Spirit comes down upon us so that we may burn as incense. We rise from this place as the Presence of God. Then, God will be pleased with the sacrifice upon the altar (v.21).

THE APOSTLES’ FAST

The Feast of SS. Peter & Paul was an ancient feast celebrated in the early Church, both in the East and the West. To accentuate the importance of these two pillars of the Christian faith, there was “The Apostles’ Fast” that preceded it, beginning shortly after Pentecost and ending on the feast day, June 29.

We have testimony from St. Athanasius the Great, St. Ambrose of Milan, St. Leo the Great, and Theodoret of Cyrrhus, all bearing witness to the importance of The Apostles’ Fast to the early Church. The earliest written texts regarding the Fast are recorded in the 4th century:

During the week following Pentecost, the people who observed the fast went out to the cemetery to pray. (A.D. 373, St Athanasius)

After you have kept the Feast of Pentecost, keep one week more festive (i.e. an ex-empt week after Pentecost), and after that, fast. It is reasonable to rejoice for the gifts of God, but after some time of relaxation, you should fast again. (A.D. 375, The Apostolic Constitutions

V, 20)

This fast was traditional all over Western Europe when the Roman rite was in use, being mentioned in 7th c. England and in the

Capitularia

of Charlemagne (issued A.D. 802) where it is de-scribed as a pious custom in the Church from time immemorial. The Roman, Anglican, and Lutheran Churches all celebrated the feast of Saints Peter and Paul. It is unclear to me when and how exactly the Apostles’ Fast ceased being celebrated in the West (If somebody knows this history, please

email Eighth Day Institute).

The Apostles’ Fast is still celebrated in the Eastern Church as a “post-Pentecostal” fast that ends on the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. While the Apostles’ Fast (or Feast Day) has no direct connection with Psalm 51, the message of being “sent out” into the world after Pentecost as a Church enlivened with The Holy Spirit is implicit in this psalm of King David as well as the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

God speaks inwardly to David’s guilt so that “God will open up his lips and his mouth will declare God’s praise.” (v. 17). Noah enters the ark in order that he may live anew when he exits the ark. God does His good when we shine forth out of Zion and “build the walls of Jerusalem” (v.20). The Great Entrance is the prologue to the Great Commission. The coming down of the Holy Spirit is for the purpose of sending out his Spirit-filled followers.

A SONG FOR ALL TO SING

I gave my heart to Jesus when I was eight years old in a Southern Baptist Church. I am now al-most 50 years down the road from that day. I have on occasion read some psalms, but have never meditated or studied them until this year. I found them repetitious and frankly boring. Now, I am sorrowful this treasure was in my open hands all along but I never took hold of it. Psalms such as Psalm 51 have transformed my worship in the Liturgy and my prayers at home. I would encourage you and others with you to take the next month and pray Psalm 51 out loud before Church on Sunday (If you are short on time, have someone read while you drive!).

Perhaps, you have never looked deeply into Psalm 51. Maybe all the talk of liturgy, priests, al-tars, eucharist, and incense—to say nothing of an Apostles’ feast day or the Apostles’ fast—is just too hazy and far away from your worship experience. While King David’s words, the movement of the Liturgy, and the participation in the Apostles’ Fast magnify and bring beauty to the message of brokenness, one can still sing this message of hope even without the accompaniment of a psalm, liturgy, or fast.

A BROKEN HEART FOR THE WORLD

For us, the Church cannot be a Temple that “meets our needs.” It cannot cater to a consumer mentality. The Church is not a business that satisfies the desires of its investors. The Church is not an organization of success. “Filling the seats” is none of its business. It is not a political force by which to get the right King on the throne. “Winning the election” is none of its business. It’s way is contradictory to all the measures of this world. The Church is the place of the broken.

Like David, we cannot say “I am not that bad of a person,” “I am not responsible for that,” or “I did nothing wrong.” Neither is the Church a place where you “accept all things” by looking away or hiding from sin. Its “acceptance” comes from staring into the cold darkness of one’s own soul. The offering of the Church is first to see who you really are before God. Many people say, “Where is this God?” The Church says, God is only as far away as your repentance. The dust and ashes of this life can, by grace, turn the mind’s eye to see the nakedness of our own heart. The broken heart is the place where we meet God.

Brokenness is not a guilt held onto—it is a guilt confronted so that it can be released. The offer-ing of our self does not smolder with embers of pride or coals of depression—by the Holy Spirit, it combusts into freedom and joy. This brokenness is for the purpose of being a whole person, and the whole person is for the purpose of the whole world. David’s psalm shows us the path of repentance—from facing the sin that burns us, to letting go of that sin as the Holy Spirit descends and Christ covers it on the altar, and to sharing that warmth of freedom with others.

Psalm 51 is a song of fire. Pentecost is a day of fire. The Eucharist is a place of fire. But we who are the Church are not consumed here. We are prepared to be sent out as apostolic flames to the world. Amen.

Mark Mosley

has done emergency medicine at Wesley Medical Center in Wichita, Kansas for over 25 years. He is boarded in Internal Medicine and Pediatrics. He received his M.D. from the University of Oklahoma. He earned his Master’s in Public Health in nutrition from Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. He is married to his wife Jane and has five children. He attends Saint George Orthodox Christian Cathedral.