Michael Polanyi: Epistemological Therapist for a Secular Age

“Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in

information?

The cycles of Heaven in twenty centuries

Bring us farther from GOD and nearer to the

Dust.”

~T.S. Eliot, Choruses

From ‘The Rock’

“A picture held us captive. And we could not get

outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us

inexorably.”

~Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

I. The

Life of Michael Polanyi

The Hungarian scientist-turned-philosopher,

Michael Polanyi, was born in Budapest in 1891 to a nonreligious, Jewish family.

His parents were among an elite circle of Hungarian intellectuals. Mark T.

Mitchell, one of Polanyi’s biographers, writes that the Polanyi children were

educated in a strict and regimented fashion. “In the morning a cold shower, an

hour of gymnastics, hot cocoa with a roll, Schiller and Goethe, Corneille and

Racine.”

A rich aesthetic diet of epic and lyric poetry, novels, and plays, I contend, occupies a key role in the story of Michael Polanyi. As a young boy, Polanyi didn’t merely encounter Beauty on the written page but was exposed to the life of the imagination through his mother’s love of the arts. His mother, Cecile, established a weekly meeting in their home’s parlor for Budapest’s most vibrant and talented artists and writers.

Polanyi later described his experience of these meetings writing, “I grew up in this circle, dreaming of great things.”

C. S. Lewis has something similar to say in an essay on the impact George MacDonald’s fairy tales had on him as a young boy. Lewis says that reading MacDonald’s fairy tales early in his life played a key role in his later conversion to Christianity. How could fairy stories lead someone to faith? Lewis’s simple answer is simple: the imagination . Indeed, Lewis says that his imagination was converted before the rest of him. He writes, “What it actually did was…baptize my imagination. It did nothing to my intellect nor (at the time) to my conscience. Their turn came far later…”

And if you’ll allow a little speculation, I wonder if something similar can be said about the role of the imagination in the life and work of Michael Polanyi. Polanyi, himself, was baptized into the Roman Catholic church in 1919. Interestingly he credited Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor and Tolstoy’s Confession with leading him to Christianity. First the imagination, then the rest.

Polanyi went on to study history, literature, language, science, and mathematics. His favorite subjects were an odd combination: physics and art history. Polanyi enrolled in the medical program at the University of Budapest and had his first academic paper published at the age of 19: “Contribution to the Chemistry of the Hydrocephalic Liquid.

By 1913 he was in Germany studying physical chemistry with a focus on thermodynamics. During his studies he wrote a paper that his mentor sent off to Albert Einstein. Einstein was impressed. He responded to Polanyi’s mentor writing, “The papers of your M. Polanyi please me a lot. I have checked over the essentials in them and found them fundamentally correct.” Polanyi described the experience of receiving Einstein’s response saying, “Bang! I was created a scientist.”

Polanyi stayed in constant contact with Einstein for the next 20 years, exchanging letters here and there. In Berlin in the 1920s Polanyi met every wednesday with a group of the world’s brightest physicists including Einstein. Polanyi said that meeting for these “informal discussions” was “the most glorious intellectual memory of my life.”

Equally important to the trajectory of Polanyi’s life was his firsthand experience of the horrors of the Great War. He saw modern warfare and the results of totalitarianism up close and this planted in him an awareness of the crumbling foundations of civilization.

Society had advanced tremendously in its knowledge of physical science and technology, and this advancement was accompanied by a sense of autonomy along with a deep skepticism of moral and religious knowledge. What was lacking were moral and spiritual checks to the technological progress of modernity.

This is where Polanyi’s most important insights began to take shape. Here’s Mark Mitchell again:

“Polanyi recognized that the prevailing conception of the scientific enterprise–characterized by the ideal of the disinterested scientist’s strict detachment from his subject matter, which could ultimately be reduced to physics and chemistry–was seriously inadequate and ultimately misleading. The scientist, according to Polanyi, is no dispassionate observer; instead, he is passionate in his quest to make contact with a reality that he necessarily believes is real and knowable. Furthermore, the practice of science requires an antecedent commitment on the part of its practitioners to such transcendent values as truth, justice, and charity. Finally, these values must exist in the context of a community of scientists who pass on the values of science to aspiring young scientists, as a master trains an apprentice. Thus...science depends for its success on such things as tradition, submission to authority, personal commitment, and moral ideals.”

The first World War came and went and left in its wake political disorder. Polanyi began to consider the problem of defending a free society from tyranny. And while his focus was originally on economics and science, eventually he became convinced that the root of the problem was epistemological. The broad conception of how knowing works, by definition, excluded moral and spiritual knowledge as realities.

As C. S. Lewis put it: “We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honor and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

How do we restore “the chest” to the man? (Keep this question in mind as we go forward.) The first and crucial step, Polanyi would say, would be acquiring a new conception of knowledge–one that unifies all knowledge and allows for knowledge of moral and spiritual realities.

In short, we need epistemological therapy. “The doctor will see you now.”

II. Personal

Knowledge

A. The

Problem: Objectivism

Polanyi called modernity’s problematic epistemology

“objectivism.” Objectivism, as a theory of knowledge, prizes “certainty” and

sees “doubt” as the avenue to all knowledge. It holds that all knowledge is

impersonal factoids. The only knowledge we can have is what is available to our

five senses and our logic.

Objectivism is, according to philosopher Esther Meek, our “defective epistemic default setting” as modern westerners. This is our problem. We wrongly think of knowledge as facts, information, proofs, and propositions. Real, true knowledge, we think, can always be explicitly put into words and sentences.

This search for certainty through the avenue of doubt is the inheritance of the western tradition of ideas. Rene Descartes’s famous phrase “I think, therefore I am” was built on doubting all the knowledge he held, especially that handed down to him through the tradition of the church.

According to Polanyi, “Descartes had declared that universal doubt should purge his mind of all opinions held merely on trust and open it to knowledge firmly grounded in reason."

Certainty became the gold standard in knowing. And that meant the eschewing of interpretation. Certain knowledge of the objective world had to be impersonal, unbiased, neutral. It needed to be objective . Data must be left uninterpreted or else it becomes contaminated by subjectivity . With certainty and doubt as our guides we sense that there is only either “absolute” truth or no truth at all. We are caught between the throes of modernity and postmodernity.

This default setting has us picturing our minds as computers that learn by downloading disconnected bits of data. When we learn something new we just read it right off of reality. It’s simple! I like to call this view of knowledge “The Pac-Man Theory” of knowledge. We just roam around the earth’s crust and simply gobble up the “dots” of facts.

And if this is what knowledge is, then of course all knowledge is propositional. It can easily be put into words and sentences. It’s explicit.

When knowledge is conceived of in this way it creates dichotomies. Meek points out that in our default setting we normally contrast knowledge to belief, facts to interpretation, reason to faith, science to art, objective to subjective. Hopefully you are beginning to sense the danger to this way of thinking.

Polanyi recognized how disastrous this view of knowledge really is. He already had an inchoate–or, tacit–sense that this was wrong by 1916. He had published a paper called “Absorption of Gases by a Solid Non-Volatile Absorbent,” which would become his dissertation. He submitted it to a chemist at the University of Budapest. The exchange between the two of them provides a clue.

Polanyi remembers that the professor studied his work and then asked him to explain a curious point in the paper. Polanyi’s result seemed to be correct, but the way he arrived at his result was faulty. Polanyi writes, “Admitting my mistake I said that surely one first draws one’s conclusions and then puts their derivations right. The professor just stared at me.”

There is a hint here of what would become Polanyi’s most famous phrase: “We can know more than we can tell.”

What Polanyi means by this phrase is that, contrary to objectivism, knowledge is not impersonal factoids that we can easily put into words. Rather much knowledge is actually tacit–or, peripheral, unspoken. In fact, Polanyi would go on to argue that all knowledge is rooted in tacit knowing.

B. The

Solution: Personal Knowledge

Remember, Polanyi left scientific research to

become a philosopher in order to save science from our epistemic default

setting. Polanyi received the opportunity to think through his views when he

was invited to give the prestigious Gifford Lectures at the University of

Aberdeen in 1951-52. This is where Polanyi fully took the turn from scientist

to philosopher. The lectures eventually turned into Polanyi’s book Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical

Philosophy

(1958).

Subsidiary-Focal

Integration

In his lectures Polanyi, for the first time,

makes his critical distinction between “focal” and “subsidiary” awareness.

Mitchell writes that this distinction “lay at the heart of his revolutionary

account of knowing.”

The modern default setting presupposes that all knowledge is focal (as opposed to tacit), meaning we focus on it and we can put it into words. But Polanyi argued that all knowing is “subsidiary-focal integration.” All knowing has two levels to it: subsidiary and focal. There is a “ from-to ” structure to all knowledge.

What does that mean?

For knowledge to ever occur there is always a combination of this two-level structure. First, we attain subsidiary (or tacit) knowledge–that is, knowledge that we cannot articulate or put into words–in the form of clues and patterns. And then we can attend from these clues and patterns to the deeper meaning. We are tacitly aware of particular clues and patterns and we indwell these clues in order to focus on the meaning. And it isn’t until these clues and patterns become tacit/subsidiary that we can focus on the true meaning.

This sounds complicated but it’s really not. Let’s take a few examples.

Example 1: The Magic Eye 3D Puzzles

In order to see the image you first become

tacitly/subsidiarily aware of clues. Those clues turn into a pattern and

eventually you are able to attend from

the

pattern to

the image.

Example 2: Driving a Stick-Shift

It isn’t until the act of pushing in the clutch

with your left leg and shifting with your right arm become tacit or subsidiary

to where you are not focusing on them, that you can begin to focus on the road and

productively drive a stick shift. When you are first learning to drive you are

so focused on shifting and where the clutch catches that you can’t actually

drive the vehicle.

What’s happening when you truly learn how to drive is that you begin to, in Polanyi’s words, “indwell” the car itself. It becomes almost an extension of your body.

Example 3: Learning to Read

Esther Meek gives the example of learning to

read as an integration between subsidiary and focal knowledge: “At some point

in your past, you looked at such letters as I am typing now, and saw

configurations of lines on a piece of paper. Your teacher made you copy them.

He/she taught you to recognize them and say them, connecting them with certain

sounds. But there came a moment when you looked and saw something new: meaning

. C-A-T became cat, and attached

suddenly to the feline who hissed when you pulled its tail.”

To begin to actually read, the particular symbols on the page become the tacit/subsidiary so that you aren’t focusing on them anymore. To read you must attend from them to the meaning of the text on the page. As long as the letters remain focal to a child, she will stumble over them, struggling to reach the meaning of the sentence. It is only when she learns to read with competence that she is able to allow the letters on the page to slip into the “tacit dimension,” almost paying them no attention at all as particulars, but seeing through them to the meaning.

The reader “indwells” the page.

Speaking a language works the same way. You don’t focusing on the syllables someone is uttering; you are only tacitly aware of them so that you can focus on the meaning of the syllables. You are indwelling the spoken words. From the syllables to the meaning. When you hear a foreign language being spoken it gives you that feeling of opacity. You can’t attend from the syllables to any meaning. All you can focus on are the noises. You feel outside. There’s no indwelling taking place.

We indwell in order to comprehend.

Example 4: Tools

One last example. The use of tools might provide

the best way to understand how indwelling works. In his book The Tacit Dimension

Polanyi gives the

example of a blind man using a probe. “Anyone using a probe for the first time

will feel its impact against his fingers and palm. But as we learn to use a

probe, or to use a stick for feeling our way, our awareness of its impact on

our hand is transformed into a sense of its point touching the objects we are

exploring.”

This applies to craftsmen as they use drills, saws, hammers, and other tools. They become extensions of their bodies. Athletes and musicians are also good examples. The last thing you want a third baseman to do when a hot grounder is hit his way is to think about it.

Polanyi demonstrates his point in The Tacit Dimension,

“Scrutinize the particulars of a comprehensive entity and their meaning...is destroyed. Such cases are well known. Repeat a word several times, attending carefully to the motion of your tongue and lips, and to the sound you make, and soon the word will sound hollow and eventually lose its meaning. By concentrating attention on his fingers, a pianist can temporarily paralyze his movement…[But] the pianist’s fingers used again with his mind on his music...they recover their meaning.”

C. How

does this integration happen?

Perhaps it is becoming clear now how the

modernist default setting for how knowledge works is incompatible with the way

we actually know and live. If real knowledge is only factoids that we can put

into sentences, then how do we ever really begin to know? How can this explain

the way we operate productively in the world around us?

The answer, Polanyi taught, was “a return to St. Augustine.” According to Polanyi, St. Augustine “taught that all knowledge was a gift of grace, for which we must strive under the guidance of antecedent belief: Unless ye believe, ye shall not understand. ” Or, “I believe in order to know.” And in St. Anselm’s famous words, we need “Faith seeking understanding.”

This is the reverse of Descartes. Descartes said that doubt was the way to knowledge. For Descartes, faith and belief undermine true knowledge.

Polanyi writes: “We must now recognize belief once more as the source of all knowledge… No intelligence, however critical or original, can operate outside such a fiduciary framework.”

“Fiduciary”: involving trust or faith, especially with regard to relationships.

In other words, whether we like it or not, all knowledge is dependent on our prior “faith commitments.” Mitchell writes, “The Cartesian ideal of achieving a God’s-eye-view from which to survey all objects of knowledge independently of any prior assumptions is an impossible dream.”

Theologian Kevin Vanhoozer puts it this way: “Knowing always takes place within the context of prior beliefs. To grow in knowledge, one must make at least a provisional commitment to a framework of thought, to accept it as ‘given’ on trust and then go on to test it.”

And the way that we come to adopt certain fiduciary frameworks is through the traditions we are born into. Tradition, contrary to Descartes’s understanding, is not necessarily an obstacle getting in the way of true knowledge. Without an authoritative tradition teaching you how to see the world, you can never learn anything.

Knowledge, Polanyi argued, is acquired in the same way an apprentice acquires knowledge of the craft from the master. By being around the master and mimicking his actions, the apprentice grows into the knowledge of the craft.

In the same way, a toddler learning how to speak must trust that the syllables her parents utter to her are not nonsense. She must first submit to their authority and take on faith that their syllables have meaning. The toddler parrots the syllables back to her parents before she knows their meaning. First faith and trust, then knowledge. “Faith seeking understanding.”

Traditions are passed on through communities of practice. Mitchell writes, “Since knowing is an art that requires one to enter into its practice through submission to the authority of a master, and since traditions are embodied in and transmitted through practices, knowing is fundamentally social.”

And if all knowledge operates this way, then even scientific knowledge requires submitting to tradition and authority.

Knowledge, understood this way, is never impersonal, unbiased, neutral, and simply objective. To think this is possible is to misunderstand how knowledge works. And to think that these are necessarily bad characteristics is to be held captive to the dominant picture of modernist epistemology.

On the contrary, knowledge is extremely personal. It involves faith and trust in a tradition. It requires the knower to personally “indwell” the known. Esther Meek suggests that rather than the knowledge being an impersonal collection of factoids, knowledge is much more akin to a covenant relationship, like a marriage. A marriage is an intensely personal relationship that involves interpersonal commitment. And by its very nature, a covenant relationship transforms both parties.

Thought of in these terms, an objectivist epistemology would be more akin to a rape. It objectifies reality into bits of information that can be impersonally utilized. But, Meek writes, “Polanyian epistemology reinstates the person in the epistemic process…” Reality, as we encounter it, she writes, is less like sentences on a page and much more like people.

This is how coming to know works: from a commitment to certain beliefs that enable you to make sense of the world around you.

Descartes’ principle of skepticism and doubt destroys itself. While he might have thought he was doubting all knowledge he had received from authorities and traditions, he was sorely mistaken. By continuing to think, write, and speak in a language he was tacitly accepting the authority of the linguistic tradition he was born into.

And once this was seen by critics like Nietzsche, the foundation of certainty upon which all modern epistemologies were built came crumbling down. And what was left over was nihilism.

D. Fact-Value Split

This has obvious

implications for what is called the fact-value split. If we agree with Polanyi

that all knowledge requires the deep participation of the knower and only

functions inside of a fiduciary framework, then it follows that all knowledge

(scientific or moral/spiritual) is on the same footing.

This opens the way for moral knowledge to be accredited once again.

Polanyi might suggest that we get “men without chests” by “birthing men without umbilical cords.”

III. Impact of Polanyi’s Thought

Polanyi has

been greatly utilized, especially by religious thinkers.

In the field of philosophy you might hear resemblances of Polanyi’s thought in folks like Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre. In fact, in 1969 Polanyi delivered a series of lectures at the University of Texas at Austin and during his time there he met informally on a weekly basis with a group of young academics. Among them: Marjorie Green, Charles Taylor, and Alasdair MacIntyre. (Polanyi has mysteriously gone largely unacknowledged by these figures.)

In the field of theology, Polanyi has been utilized by influential theologians such as T. F. Torrance, Lesslie Newbigin, Tim Keller, Kevin Vanhoozer, and Fr. Andrew Louth.

Let me gesture towards some possible areas where Polanyi might have something to say. Perhaps these areas can serve as catalysts for discussion.

A. Religion in the Public Square

Finally, if

Polanyi is right, then the idea of a neutral, unbiased, objective, a-religioius

public square needs to be discarded.

If all knowledge is on the same epistemic footing, then should we be accrediting moral and spiritual knowledge in the public square?

If you prioritize a certain type of knowledge in a society (i.e., scientific knowledge), then you arguably end up privileging certain cultures and people with training who speak those ways.

Is this vision for knowledge necessary for any truly democratic public square?

B. Apologetics and the Imagination

Modern

evidentialist apologetics attempts to prove with certainty such propositions

as, “God exists,” or “Jesus was raised from the dead,” or “The Bible is

infallible.”

Lesslie Newbigin writes, “The assumption often underlying [modern apologetics] is that the gospel can be made acceptable by showing that it does not contravene the requirements of reason...This is a mistaken policy...To look outside the gospel for a starting point for the demonstration of the reasonableness of the gospel is itself a contradiction of the gospel, for it implies that we look for the logos elsewhere than in Jesus.”

Perhaps what apologetics needs is an appeal to the imagination. Beauty through art, story, and practices. Art is usually seen as an extra or superfluous thing. But if Polanyi is right, then the arts are about a type of knowledge in the same way that chemistry is.

This gets at Charles Taylor’s notion of the “social imaginary.” Apologetics should work toward the conversion of the social imaginary.

C. Liturgy

Polanyi

himself pointed to the possible role of liturgy to Christian belief and

knowledge.

He writes that Christian liturgies serve as “frameworks of clues which are apt to induce a passionate search for God.”

I suggest that we think of the liturgy in Polanyi’s “from-to” structure of knowledge: subsidiary-focal integration. Can we discern clues and patterns in our liturgies (scripture readings, creedal confessions, sermons, hymns, corporate prayers, the Eucharist) and can these be indwelt by the skillful practitioner in order to see their meaning?

Perhaps we can reason from the liturgy to an intimate knowledge of God Himself.

D. Scripture and Tradition

What about

the Scripture vs. tradition debate?

If we get rid of the two thousand years of church tradition with a (naive) desire to interpret Scripture apart from how the tradition (i.e., Creeds and “masters of the craft”) has in the past, what you will end up with is not the cold hard facts of what St. Paul really said–as the historical-critical method would have you believe. Rather, much like an unlearned and unskilled apprentice in a workshop, you will most likely put yourself and those around you in danger somehow.

After all, Scripture refers to itself as a sword. And swordsmanship is certainly a skill that requires practice and submission to a master swordsmanship.

Polanyi might suggest to us that there is no divide between Scripture and tradition if we understand it rightly. It is within Scripture that we come before the face of God. And it is there that we find that the face Scripture reveals is Christ’s. In order to attend to the deeper meaning of Scripture, which is Christ, we indwell them by the “tool” of the church’s great tradition. We submit to tradition and let it teach us how to read the Bible.

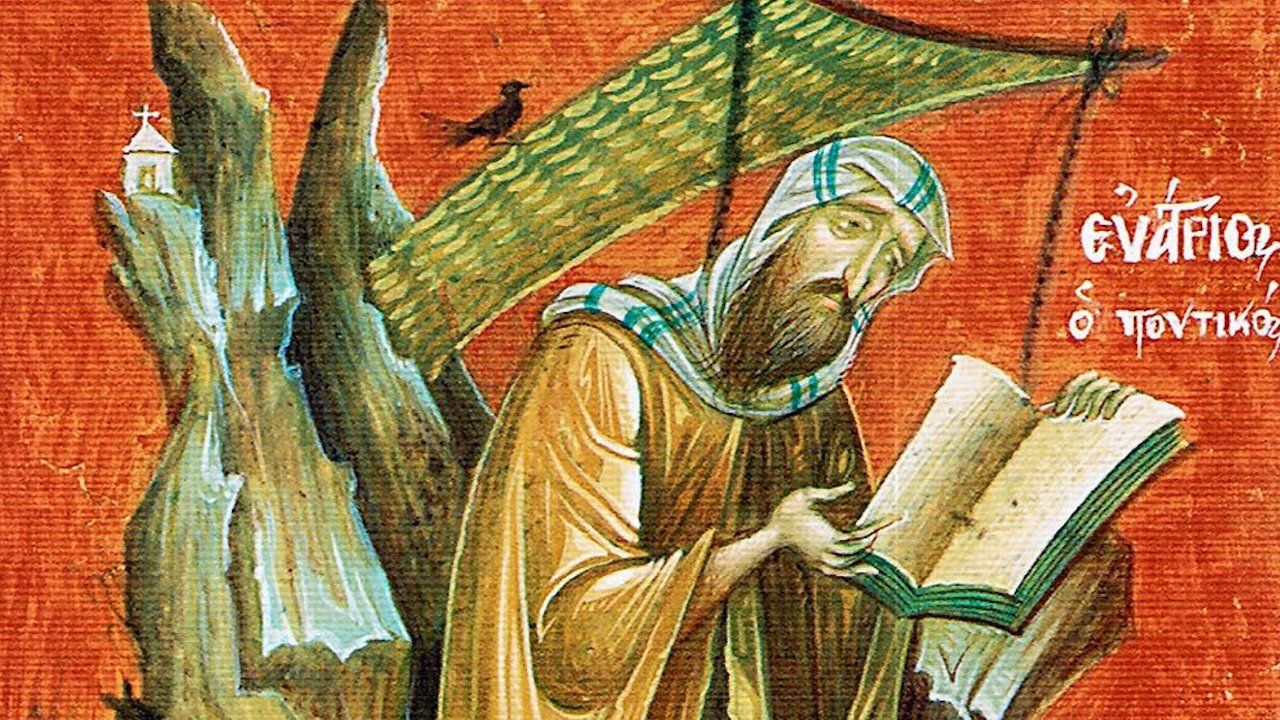

Feast of St. Eustathius the Great Martyr, His Wife & Two Children

Anno Domini 2019, September 20

*Originally

delivered at Hall of Men in Wichita, KS on August 8, Anno Domini 2019.

Cameron Combs is a pastor at an Assemblies of God church in Wichita, KS. He earned a M.A. from Biola University in 2016 and he loves to read anything from Sci-Fi to philosophical theology.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.