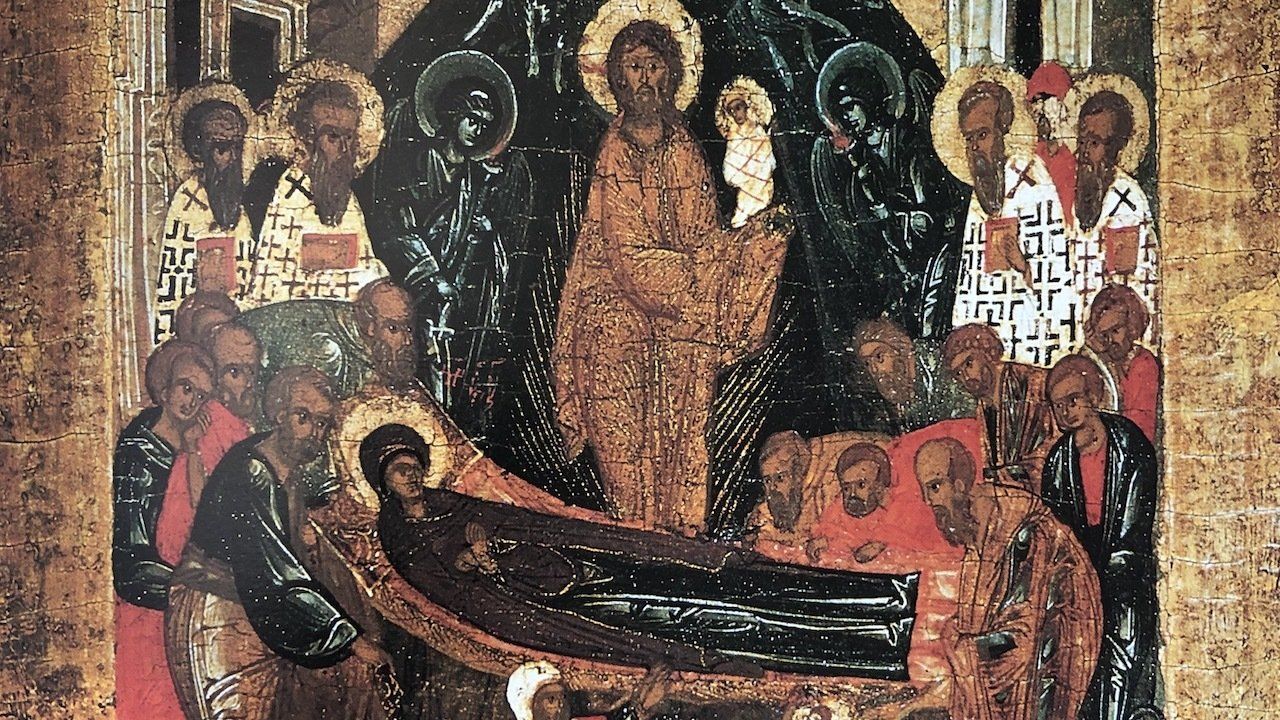

16th century Russian icon of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

The feast of the Dormition (χοίμησις = sleep, rest, repose) of the Mother of God, known in the West under the name of the Assumption, comprises two distinct but inseparable moments for the faith of the Church: firstly, the Death and Burial, and second, the Resurrection and Ascension of the Mother of God. The Orthodox East has known how to respect the mysterious character of this event which, unlike the Resurrection of Christ, was not made a subject of apostolic preaching. In fact, there is here a mystery, not destined for ears of “those without,” but revealed to the inner consciousness of the Church. For those who are affirmed in faith in the Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord, it is evident that, if the Son of God assumed His human nature in the womb of the Virgin, She Who served the Incarnation had in Her turn to be assumed into the glory of Her Son risen and ascended to Heaven. “Arise, O Lord, into Thy rest; Thou, and the ark of Thine holiness” (Ps. 131:8). “The grave and death” could not retain the “Mother of Life,” for Her Son has transported Her (μετέστησεν) into the life of the future age (Kontakion, Tone 2).

The glorification of the Virgin Mary is a direct result of the voluntary humiliation of the Son: the Son of God is incarnate of the Virgin Mary and is made “Son of Man,” capable of dying, whilst Mary, becoming the Mother of God, receives “the glory which belongs to God” (θεοπρεπὴς δόξα) and is the first among human beings to participate in the final deification of the creature (Vespers, Stich. of Tone 1). “God became man, that man might become God” (SS. Irenaeus, Athanasius, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa, et al). The significance of the Incarnation of the Word thus appears at the end of Mary’s life on earth. “Wisdom is justified of her children.” The glory of the age to come, the last end of man, is already realized, not only in a Divine Hypostasis made flesh, but also in a human person made God. This passage from death to life, from time to eternity, from terrestrial condition to celestial beatitude establishes the Mother of God beyond the general Resurrection and the Last Judgment, beyond the Second Coming which will end the history of the world. The feast of August 15th is a second mysterious Easter, since the Church therein celebrates, before the end of time, the secret first-fruit of its eschatological consummation. This explains the soberness of the liturgical text which, in the office of the Dormition, permits a glimpse of the ineffable glory of the Assumption of the Mother of God (The office of the “Burial of the Mother of God” on August 17 is of very late origin, and is on the contrary too explicit; it is copied from the Matins of Holy Saturday for the “Burial of Christ”).

The feast of the Dormition probably originated in Jerusalem. However, at the end of the 4th century, Aetheria did not yet know it. It can nevertheless be supposed that this solemnity was not slow in appearing, since in the 6th century it was already widespread; St. Gregory of Tours is the first witness of the feast of the Assumption in the West (De Gloria martyrum, Miracula 1:4, 9), where it was originally celebrated in January (Bibbio Missal and Gallican Sacramentary indicate January 18th as the date). Under the Emperor Maurice (A.D. 582 to 602) the date of the feast was definitely fixed as August 15th (cf. Nicephorus Callistus, Hist. Eccles. 17:28).

Among the first iconographic monuments of the Assumption must be noticed the sarcophagus of Santa Ingracia at Saragossa (beginning of the 4th century) with a scene which is very probably that of the Assumption, and a relief of the 6th century, in the Basilica of Bolniss-Kapanakči, in Georgia, which represents the Ascension of the Mother of God and is matched by a relief of the Ascension of Christ. The apocryphal account which circulated under the name of St. Melito (2nd century) was not earlier than the beginning of the 5th century. It is full of legendary details of the death, the resurrection, and the ascension of the Mother of God, dubious information that the Church will take care to avoid. thus, St. Modestus of Jerusalem (d. A.D. 634), in his “Praise on the Dormition,” is very restrained in the details which he gives: he notes the presence of the Apostles “brought from afar, by an inspiration from on high,” the appearance of Christ, come to raise the soul of His Mother, finally, the return to life of the Mother of God, “in order to participate corporally in the eternal incorruption of Him, Who brought Her forth from the tomb and drew Her to Himself in a manner that He alone knew.” The homily of St. John of Thessalonica (d. circa A.D. 630) as well as other more recent homilies—St. Andrew of Crete, St. Germanos of Constantinople, St. John Damascene—are more rich in details, which were to enter both into the liturgy, and into the iconography of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

The classical type of the Dormition in orthodox iconography is habitually limited to representing the Mother of God lying on Her deathbed, in the midst of the Apostles, and Christ in glory receiving in His arms the soul of His Mother. However, sometimes there has been a desire to show equally the moment of the bodily assumption: one then sees, at the top of the icon, above the scene of the Dormition, the Mother of God seated on a throne in the “mandorla” that angels are carrying towards the heavens.

In our icon (Russian, 16th cent.) Christ in glory surrounded by a “mandorla” is looking at the body of His Mother stretched on a litter. He is holding on His left arm a small figure of a child clothed in white and crowned with a halo: it is the “all-luminous soul” that He has just gathered up (Vespers, Stich. of Tone 5). The twelve Apostles, “standing around the bed, look on with terror” at the decease of the Mother of God (Vespers, Stich. of Tone 6). It is easy to recognize, in the foreground, St. Peter and St. Paul on either side of the couch. On some icons there is shown at the top, in the sky, the moment of the miraculous arrival of the Apostles, assembled “from the ends of the earth, on the clouds” (Kontakion, Tone 2). The multitude of angels present at the Dormition sometimes forms an outer border around the “mandorla” of Christ. On our icon, the heavenly virtues, accompanying Christ, are indicated by a seraphim with six wings, two cherubim, and two angels in the mandorla. Four bishops with haloes stand behind the Apostles. They are St. James, “the brother of the Lord, the first Bishop of Jerusalem, and three disciples of the Apostles: Timothy, Hierotheus, and Dionysius the Areopagite, who had come with St. Paul (cf. passage on the Dormition in Divine Names by Dionysius the Areopagite, 3:2). Sometimes groups of women represent the faithful of Jerusalem who, with the bishops and the Apostles, form the inner circle of the Church in which is accomplished the mystery of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

The episode of Athonios, a fanatical Jew, who had both hands cut off by the sword of an angel, for having dared to touch the funeral couch of the Mother of God, figures in the majority of the icons of the Dormition. The presence of this apocryphal detail in the liturgy and in the iconography of the feast is to recall that the end of the life on earth of the Mother of God is an intimate mystery of the Church which must not be exposed to profanation: inaccessible to the view of those without, the glory of the Dormition of Mary can be contemplated only in the inner light of Tradition.

*Originally published in Leonid Ouspensky and Vladimir Lossky, eds., The Meaning of Icons

(Bern/Olton: URS Graf Verlag, 1952). Revised by St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press in 1982 and available for purchase at Eighth Day Books.