Question: “As a pure and spotless lamb, Christ was foreknown before the foundation of the world, yet manifested at the end of time for our sake” (1 Pet. 1:20). By whom was Christ “foreknown?”

Response: The scriptural text calls the mystery of Christ “Christ.” The great Apostle clearly testifies to this when he speaks of the mystery hidden from the ages, having now been manifested (Col. 1:26). He is of course referring to Christ the whole mystery of Christ, which is, manifestly, the ineffable and incomprehensible hypostatic union between Christ’s divinity and humanity. This union draws his humanity into perfect identity, in every way, with His divinity, through the principle of person (ὑπόστασις); it is a union that realizes one person composite of both natures, inasmuch as it in no way diminishes the essential difference between those natures. And so, to repeat, there is one hypostasis realized from the two natures and the difference between the natures remains immutable. In view of this difference, moreover, the natures remain undiminished, and the quantity of each of the united natures is preserved, even after the union. For, whereas by the union no change or alteration at all was suffered by either of the united natures, the essential principle of each of the united natures endured without being compromised. Indeed that essential principle remained inviolate even after the union, as the divine and human natures retained their integrity in every respect. Neither of the natures was denied anything at all because of the union.

For it was fitting for the Creator of the universe, who by the economy of His incarnation became what by nature He was not, to preserve without change both what He Himself was by nature and what He became in His incarnation. For naturally we must not consider any change at all in God, nor conceive any movement in Him. Being changed properly pertains to movable creatures. This is the great and hidden mystery, at once the blessed end for which all things are ordained. It is the divine purpose conceived before the beginning of created beings. In defining it we would say that this mystery is the preconceived goal for which everything exists, but which itself exists on account of nothing. With a clear view to this end, God created the essences of created beings, and such is, properly speaking, the terminus of His providence and of the things under His providential care. Inasmuch as it leads to God, it is the recapitulation of the things He has created. It is the mystery which circumscribed all the ages, and which reveals the grand plan of God (cf. Eph. 1:10-11), a super-infinite plan infinitely preexisting the ages. The Logos, by essence God, became a messenger of this plan (cf. Is. 9:5, LXX) when He became a man and, if I may rightly say so, established Himself as the innermost depth of the Father’s goodness while also displaying in Himself the very goal for which His creatures manifestly received the beginning of their existence.

Because of Christ—or rather, the whole mystery of Christ—all the ages of time and the beings within those ages have received their beginning and end in Christ. For the union between a limit of the ages and limitlessness, between measure and immeasurability, between finitude and infinity, between Creator and creation, between rest and motion, was conceived before the ages. This union has been manifested in Christ at the end of time, and in itself brings God’s foreknowledge to fulfillment, in order that naturally mobile creatures might secure themselves around God’s total and essential immobility, desisting altogether from their movement toward themselves and toward each other. [see footnote 7 below] The union has been manifested so that they might also acquire, by experience, an active knowledge of Him in whom they were made worthy to find their stability and to have abiding unchangeably in them the enjoyment of this knowledge.

*Footnote 7: Maximus here refers to the absolute stability (στάσις) which is the goal (τέλος) of all creaturely movement, a notion which he elsewhere (Ambiguum

7) directed against the Origenist cosmology in which true stasis is that original, primordial spiritual unity “around the Divine” (περὶ θεῖον, Epistle 6) or around God’s immobility, which brings everything to sabbatical completion. Maximus is sympathetic to Gregory of Nyssa’s image of the ultimate “repose” as secured precisely in “perpetual striving” (ἐπέκτασις), an eternal purposive movement around the God whose essence remains impenetrable. On the philosophical and theological ramifications of this notion, see Paul M. Blowers, “Maximus the Confessor, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Concept of ‘Perpetual Progress,’” pp. 151-71. On the ascetic implication of this notion, see Ad Thalassios 17 (translated in same volume, pp. 105-8).

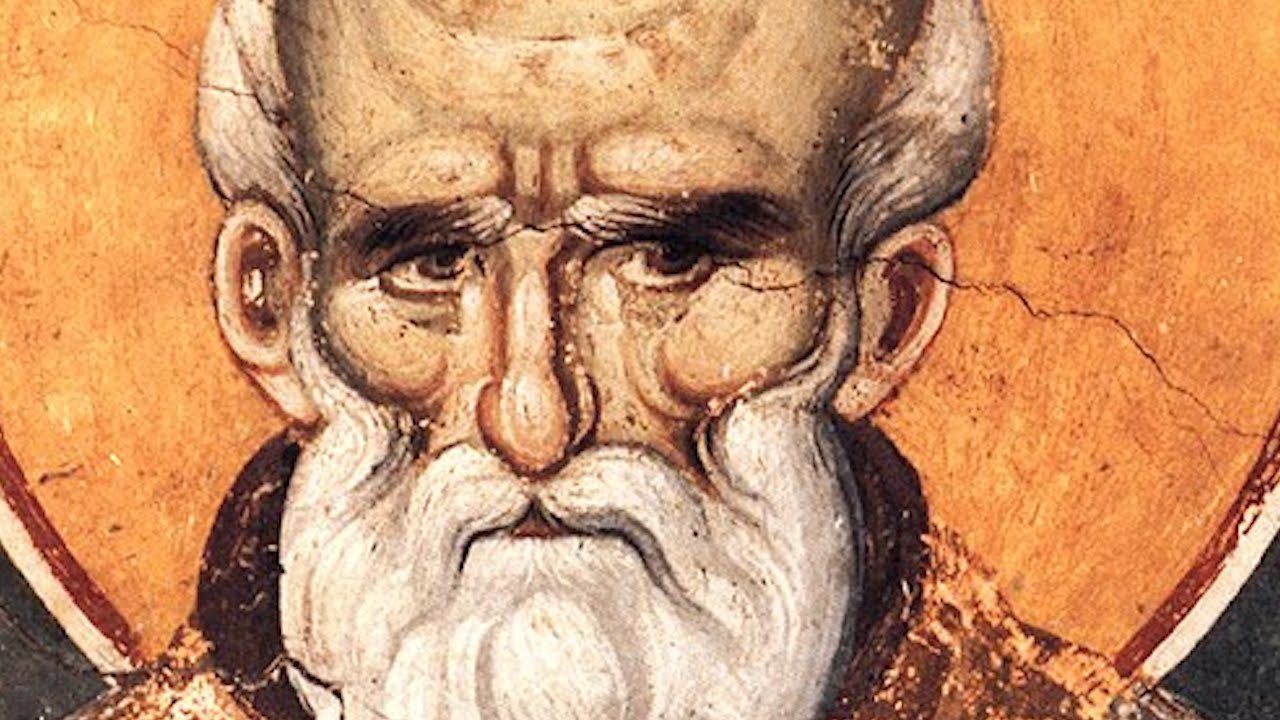

**Excerpt from St. Maximus the Confessor, On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ, tr. Paul M. Blowers and Robert Louis Wilken (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminar Press, 2003), 123-126. Available for purchase at Eighth Day Books.