Oikophilia: An Invitation to Join David Jones in His Home of Sacrament and History

by Fr Gabriel Rochelle

Feast of the Martyr Hermeningilda the Goth of Spain

Anno Domini 2020, November 1

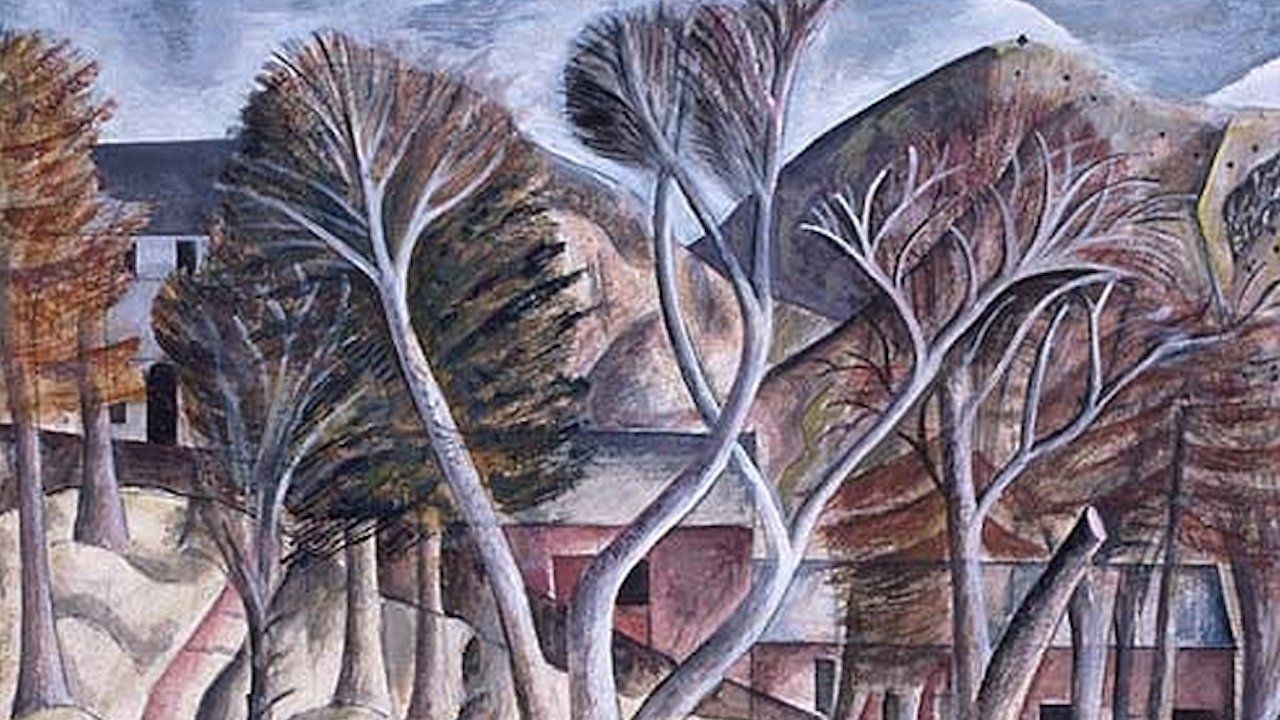

Capel-y-ffin by David Jones (1926)

David Jones never owned property in London. He never owned his own house or flat. Instead, he lived in a variety of places, including the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic set up by Eric Gill, first at Ditchling and subsequently at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales near the English border. He was often able to carry on only because of the generosity of his benefactors, especially Helen Sutherland, a very wealthy Quaker who befriended him in 1929. She became his chief patron and often supported him until her death in 1966 [1]. Jones spent two periods in hospitals due to nervous breakdowns that were a direct result of his PTSD, which he appears to have written his way out of by creating the epic poem called In Parenthesis. His physical circumstances were often grim and there was a time in late 1945 when he was so poor that he became undernourished. Jones seems to have lived out the myth of the starving artist almost to the point of homelessness.

That said, Jones had a deep love of home, an oikophilia to use Roger Scruton’s term. But we have to be willing to see what home meant to him. His Wales has a time-bound framework: at one end is the withdrawal of the Romans from the British Isles at the time of Cunedda, the first king of North Wales, in the early 5th century; and at the other, the specific date of 11 December 1282, the assassination of Llewelyn ap Gruffudd, the last true Prince of Wales. This was a date all his friends had to memorize. These are the temporal boundaries for his Welsh sensibilities, and the time between these dates inspires his sense of hiraeth.

In my estimation, Welshness and hiraeth merge in David Jones’s life and work. They form the psychological basis upon which he constructed a home in this world. Sign and sacrament are the theological blueprint for the home; the structural framework is the palimpsest of British history, myth, and legend.

I submit that sacrament and history were his home, and he lived out of that home in everything, whether artworks or writing or conversations with friends. At the same time, he invited all of us to join him in his home. The invitations are written in paint and words. For David Jones the past was an unbroken unity; it was the past of the “ancient Britons,” the Welsh who in language and myth preserved the sacred history of the British Isles. But he worried and supposed that it might never be so again in the future. In a letter to Vernon Watkins, he wrote, “For the ‘poet’ or the ‘artist’ the ‘past’ is much what ‘nature’ is to him—it is the raw stuff which he uses. But when that ‘past’ is virtually forgotten and available perhaps only in another linguistic tradition and moreover a tradition separated from us by centuries of a contrary tradition, then the poeta is in a real jamb” [2]. Kathleen Raine observed that Jones affirmed the advent of the new Dark Age T. S. Eliot foresaw, a Dark Age of which the loss of cultural values and memories would be the bellwether [3]. Insofar as we perceive ourselves to be living in a new Dark Age, we may see him as a forerunner to our plight.

Sacrament and history come together perhaps most clearly and poignantly in the first poem we consider today, entitled “The Tutelar of the Place,” contained in The Sleeping Lord. This word tutelar is an old Latin term for the protector of a particular place. The tutelar is frequently a local deity. The “Tutelar” poem follows an introductory poem and four more poems which have in common an imperial Roman setting. “The Tutelar of the Place” serves as a bridge to the two “Welsh” sections: “The Hunt” and “The Sleeping Lord” [4]. The theme of the poem is the universal sanctity of the local place, the spiritual essence of hill (tump) and stone tied up with myth and history—a note we saw in Emrys Humphreys’ words about “the original language which hallows every hill and valley, every farm and every field with its own revered name.” The conclusion to the poem is a prayer about the fear of apocalypse on one hand, and the hope of bare but promising survival on the other. A sense of grim foreboding is afoot in this poem. The notes are clear: the government, once Rome and now Westminster, may take over or subsume everything with its materialism and its insistence on that which is utile (useful) as the very essence of life. Here again we see in Jones’s thinking the influence of Spengler and Dawson.

Sweet Jill of the hill hear us

Bring slow bones safe at the lode-ford

Keep Lupa’s bite without our wattles

Make her bark keep children good

Save us all from dux of far folk

Save us from the men who plan [5].

When the technicians manipulate the dead limbs of our culture as though it yet had life, have mercy on us. Open unto us, let us enter a second time within your stola-folds in those days—ventricle and refuge both, hendref for world-winter, asylum from world-storm. Womb of the Lamb the spoiler of the Ram [6].

What we need to grasp about the poem “Tutelar” is that Jones presents the Virgin as a local deity in a local place. The place is undefined in the poem, but we recognize it as the British Isles in toto. The Virgin Mary is at once the Earth Mother, she is Rhiannon the euhemerized goddess of the first Branch of the Mabinogion, she is Gwenhwyfar the love of King Arthur. She is Theotokos. And “the Tutelar of the Place” and the place is important. For she brings sanctity to all the layers of myth and history in the place where she abides. As Samuel Rees observed, “In short (the poem) is asking for a rebirth through the protection and intercession of Mair or the Virgin Mary that will enable man and child [, Jack of the Tump,] to survive the ‘world-storm’ in the latter day, ‘the December of our culture’” [7].

It is the specificity that we observe in this poem, a specificity of the place, a specificity presented as palimpsest on one hand, and as anamnesis on the other. The palimpsest aspect enables us to see history and myth as if it were an archeological site, with strata from different eras contributing their names and artifacts across history to create a heap of meaning. By the anamnesis aspect, we enter these strata, remembering their significance for each era and their meaning for today. In the remembrance of this layered history we shall find meaning for our own lives, a history mediated through the prism of Christian faith and the eucharistic memorial.

“The Tutelar” offers perceptive ways of viewing the local history and the individual’s ties to it that inform the present time and space apart from the need to be in that place. In Jones’s poem, we are given a place within the self and within history that transcends specific locale while yet evoking a specific locale. Even if Jones’s allusions elude us because we are not Anglo-Welsh, we get his main point: by the gifts of both anamnesis and palimpsest we become embedded in a peculiar multilayered history that informs our present with actual—not potential—meaning. David Jones has, in essence, anticipated anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s concept of “thick description,” meaning the binding of the subjective meanings and interpretations of a place with the social actions that people perform there. This experience is as available to us today as it was to Jones if we are willing to explore our history and sacramental life in depth [8].

The second poem to consider, briefly, is part VI of Anathémata, called “Mabinog’s Liturgy.” Be not confused: this is not a liturgy as we think of it. It is a magnificent consideration of the incarnation as the heart of the world. Mabinog recalls the Mabinogion, the principal folk tales of the Welsh with which Jones had great familiarity from childhood. The word Mabinogi originally meant the youthful adventures of a hero, but the meaning expands to encompass the adventures of a hero throughout his life. Here the mabinog/hero is Jesus Christ.

In the poem Jones weaves together history, myth, legend, and the liturgy beginning from SW Germany, the original home of the Celts, whence “West-Raum seekers brought La Tène to Thameside” [9]. He weaves this history and its personalia together with the warp threads of the Latin mass for Christmas, Epiphany, and surrounding holidays, so that Mary may interweave with Gwenhwyfar and Christ with King Arthur.

What says his mabinogi?

Son of Mair, wife of jobbing carpenter

In via nascitur

Lapped in hay, parvule.

But what does his Boast say?

Alpha es et O

That which

The whole world cannot hold.

Atheling to the heaven-king.

Shepherd of Greekland.

Harrower of Annwn.

Freer of the Waters.

Chief Physician and

Dux et pontifex.

Gwledig Nefoedd and

Walda of every land

Et vocabitur WONDERFUL [10].

The overlapping of cultures is here so powerful as to need little comment. As Paul Robichaud notes, “Jones evokes the many strands making up early medieval Europe—the Germanic, Byzantine, Celtic and Latin cultures—as well as the convergence of pagan ritual, classical science, and Roman discipline in the cultural and intellectual forms of European Christendom. Christianity brings spiritual and cultural unity to the ancient world, and ‘Mabinog’s Liturgy’ explores this process as it evolves in Britain.”[11] Jones has found his true home, nestled in the liturgical framework of the eucharist and, here, oriented around the Nativity.

We have stressed Jones’ ability to make the past present throughout, but we need to add a note about the future. Recall that Jones disagreed with Spengler’s pessimistic outlook on the future of civilization “on metaphysical grounds.” I believe this is because he saw anamnésis as moving forward as well as to the past. In the liturgical hymn “Give us a foretaste of the feast to come,” we can see that not only do we remember the past, but we also remember the future as the ground of our hope [12]. This understanding of anamnésis was not foreign to David Jones.

I received a copy of In Parenthesis in 1979 from a poet friend, Wally Swist, now of Amherst MA. Wally knew of my interest in the Great War and of my special interest in the War poets. He worked in a bookstore that specialized in poetry and he brought me In Parenthesis as a gift. I had read many poems and histories about the Great War, but In Parenthesis was a totally different experience. Here’s the point, and this is crucial to all that I have said about Jones’s writing and art. This book was not about the War, this was the War. The reader becomes a foot soldier in the trenches of Belgium and France. David Jones had managed, by the incessant layering of his materials, to concoct a tale which zigzags across history by which the reader is immersed, if not engulfed, in the experience of war. In short, he had made the past present. There is literally no other book or poem about the Great War which has the ability to affect you on a deep visceral and personal level than In Parenthesis. Of his work it was noted shortly after his death, “David Jones takes this great heap of the past and tells it not as history, but as something we have experienced in our own flesh; it is closer to direct memory than anything else” [13].

David Jones’s true home is entered through anamnésis, through making the past present. For him, the armature around which all other history, myth, and legend is wrapped is the initial anamnesis of the eucharist. All of history finds its center point in the passion and resurrection of Christ with its re-presentation in the Eucharist. For Jones the past is a whole that goes back even into the rock and tumulus of prehistory, and it is all personal and present in each of us.

There is no need for imagination when you approach David Jones’s principal writings. One senses no pretension, no artifice, no attempt to convince you of the truths he tells, and above all no phony representations. He merely sets them out so that you can taste and touch them as if they were your own. In a most enchanting way, he makes the past present.

I suggest then, this lesson for us: in a time of dissolution, when we sense ourselves at a “break” between eras as did Jones and his friends, when culture has given way to the planners and the technicians as he suspected, we need a home. And for us it can be the same as for Jones: our multilayered history and the eucharist as the center for our lives and our true home, for “we have here no abiding city” [14].

[1] Thomas Dilworth,

David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet (Counterpoint Press: Berkeley, 2017), pp. 121, 336.

[2] David Jones, Letters to Vernon Watkins, ed. with notes by Ruth Pryor (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1976), p. 58.

[3] Kathleen Raine, “The Sign-Making of David Jones”, in The Iowa Review, vol. 6 issue 3, Summer-Fall 1975, pp.96-101.

[4] See Rene Hague, David Jones, Writers of Wales series (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1975), p. 67.

[5] “The Tutelar of the Place,” pp. 60f. in The Sleeping Lord.

[6] Ibid., p. 64. Hendref is Welsh for “ancestral dwelling” or “winter-shelter.”

[7] Samuel Rees, David Jones, Twayne’s English Author Series 246 (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1978), p. 111.

[8] Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

[9] Anathémata, p. 185.

[10] Ibid., pp. 207f.

[11] Paul Robichaud, Making the Past Present: David Jones, the Middle Ages, & Modernism (Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2007), p. 136.

[12] On this twofold meaning of anamnésis, consult the excellent older work by Dietrich Ritschl, Memory and Hope (New York: Macmillan, 1967).

[13] N. K. Sandars, “The Present Past in the Anathemata and Roman Poems,” in Roland Mathias, ed., David Jones: Eight Essays on his Work as Writer and Artist (Llandysul, Dyfed: Gomer Press, 1976), p. 53. Italics mine.

[14] Heb. 13:14; see also I Pt. 2:11.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.