Social reality is malleable. How it is depends upon how it is perceived; and how it is perceived depends upon how it is described. Hence language is an important instrument in modern politics, and many of the political conflicts in our time are conflicts over words.

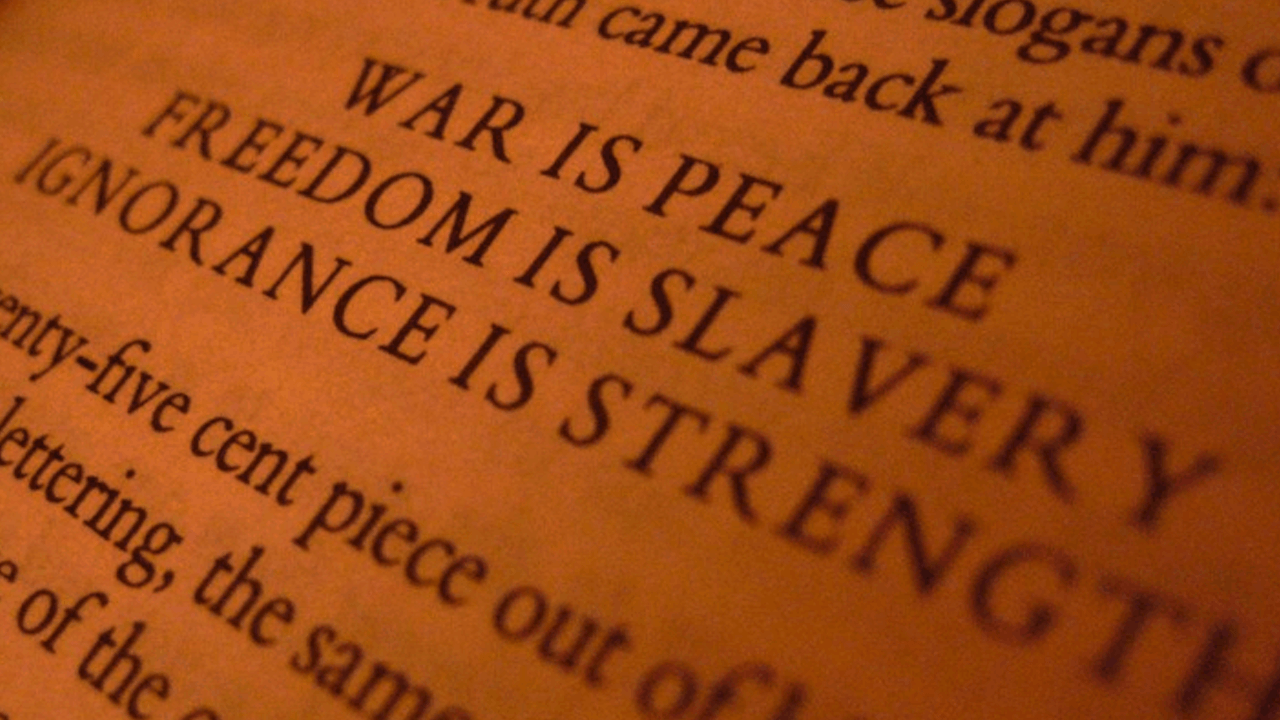

Perhaps the most obvious instance of this is provided by Soviet-style communism, and the invention of the language that we know, thanks to Orwell’s 1984, as Newspeak. Many of the terms of this language were taken from Marx; but they were grafted on to a native Russian habit of distinguishing things by their labels. Who and what am I? Who and what are you? Those are the questions that plagued the Russian romantics, and to which they produced answers that mean nothing in themselves, but which dictated the fate of those to whom they were applied. I am a member of the intelligentsia, you are a Narodnik; I am a nihilist, you are an anarchist; I am a progressive, you are a reactionary. What a gift to those “beautiful souls,” when the description “communist” was offered on a plate, and with it a whole system of labels, by which to distinguish the good from the bad by the simple use of a word! Humanity, the Russian intelligentsia discovered, divides into classes—and what beautiful words, full of the sound of European culture, were used to describe them: bourgeoisie and proletariat; capitalist and socialist; exploiter and producer: and all with the simple and glorious meaning of them and us!

The course of communist politics should be understood in terms of the power of labels. Each of those who emerged triumphant from the Second International knew that he had been granted a vision that fully authorized his conduct. This Gnostic revelation was so clear that no argument was necessary, and no argument possible, that would provide it with a justifying proof. All that mattered was to distinguish those who shared the vision from those who dissented. And the most dangerous were those who dissented by so small a margin that they threatened to mingle their energies with yours, and so pollute the pure stream of action.

From the beginning, therefore, labels were required that would stigmatize the enemy within and justify his expulsion: he was a revisionist, a deviationist, an infantile leftist, a utopian socialist, a social fascist and so on. The original division between Menshevik and Bolshevik epitomized this process: those peculiar fabricated words, which were themselves crystallized lies, since the Mensheviks (minority) in fact composed the majority, were thereafter graven in the language of politics and in the motives of the communist elite. The success of these labels in marginalizing and condemning the opponent fortified the communist conviction that you could change reality by changing language. You could create a proletarian culture, just by inventing the word “proletcult.” You could bring about the downfall of the free economy, simply by shouting “crisis of capitalism” every time the subject arose. You could combine the absolute power of the Communist Party with the free consent of the people, by announcing communist rule as “democratic centralism.”

How easy it proved, to murder millions of innocents, when nothing worse was occurring than “the liquidation of the kulaks.” How simple a matter, to confine people for years in miserable camps, engaged in slave-labor until they sicken or die, if the only thing that language permits us to observe is “re-education.” The Nazis followed the example, and invented a Newspeak of their own. They learned that the silencing of opponents is not tyranny when described as Gleichschaltung

[Synchronization], and that mass murder is no such thing when carried out as a “final solution.”

Newspeak occurs whenever the main purpose of language—which is to describe reality—is replaced by the rival purpose of asserting power over it. The fundamental speech-act is only superficially represented by the assertoric grammar. Newspeak sentences sound like assertions, but their underlying logic is the logic of the spell. They show the triumph of words over things, the futility of rational argument and also the danger of resistance. As a result Newspeak developed its own special syntax which—while closely related to the syntax deployed in ordinary descriptions—carefully avoids any encounter with reality or any exposure to the logic of rational argument. This Françoise Thom has tried to show in her brilliant study, La langue de bois

[Double talk; published in English, tr. C. Janson, Newspeak, London: Claridge Press, 1985]. I will be taking her argument forward by considering another and newer kind of “langue de bois,” namely that which has emerged with the European Union, and which has become the official language of the Commission. The purpose of communist Newspeak, in François Thom’s ironical words, was “to protect ideology from the malicious attacks of real things.” The purpose of Eurospeak is not to protect an ideology, but to protect a system of privileges. Hence the underlying logic is not that of the spell but that of the mystery, in which challenging questions are finally shown to be unanswerable, and therefore unaskable. At the same time, like Newspeak, Eurospeak exemplifies an evasiveness towards rational argument, and an intolerance towards any opposition to the fundamental agenda.

The distinction between Newspeak and Eurospeak can be grasped through an example of each. The Newspeak term “capitalism,” which has entered the language in another sense, refers strictly to the system mythopoeically described in Das Kapital—in other words to a system of economic control in which private property is all in the hands of a non-producing “bourgeois” class. Used in such phrases as “the crisis of capitalism,” “capitalist exploitation,” “capitalist ideology” and so on, the term functions as a kind of spell, the equivalent in economic theory of Krushchev’s great scream from the rostrum of the United Nations: “We will bury you!” By describing free economies with this term, Newspeak casts the spell that extinguishes them. The reality of the free economy disappears behind the description, to be replaced by a strange baroque edifice, constantly falling to the ground in a dream-sequence of ruin.

This is not to say that there is not a perfectly serious use of the term “capitalism” in economic theory. We can disagree with the central argument put forward by Marx in Das Kapital, while accepting that there is such a thing as economic capital, and such a thing as its private deployment. And we might describe an economy in which substantial capital is in the hands of private individuals as capitalist, meaning that term as a neutral description that may. Or may not, in due course, form part of a theory that uncovers the truth. But that is not how the term is used in Newspeak, which has no place for neutral descriptions and should be understood as a defense against truth, rather than a means to embrace it.

We should here compare the Eurospeak term “subsidiarity.” This term, too, has a legitimate use. When embedded in Eurospeak, however, “subsidiarity” loses its referential character, in just the way that “capitalism” loses its referential character in Newspeak. Encountering the term “subsidiarity” in the documents of the EU you enter the vicinity of a mystery, from which you are expected to learn only one thing, which is that enquiry is futile. The term invariably occurs in the vicinity of a seriously damaging question, namely: what remains of the democratic forms of government achieved by the nation states, when the EU takes charge of their legislation? The answer is that we must apply the “principle of subsidiarity,” according to which decisions are all to be taken at the “lowest level compatible with the project of Union.” “What is the lowest level?” you may ask, and “Who decides which decisions are to be taken there?” The only possible answer to the second of those questions—namely, “the EU apparatus, including the European Court of Justice”—removes all meaning from the first. To say that the nation states have sovereignty in all matters that they are competent to decide, but that the EU apparatus decides which matters those are, is to say that the nation states have no sovereignty at all, since all their powers are delegated. In other words, “subsidiarity” effectively removes the sovereignty that it purports to grant, and so wraps the whole idea of sovereignty in an impenetrable cloud of mystery. True, the EU Constitutional Treaty incorporated a protocol reaffirming the principle of subsidiarity, and requiring EU institutions to show evidence, before taking charge of some matter, that it cannot be dealt with at the national level. But the standard of proof is vague, and the arbiter appointed is the European Court of Justice, an institution committed to the project of “ever closer union,” under whose jurisdiction the acquis communautaire

has already expanded to 97,000 pages. Hence the protocol again merely removes the guarantees that it purports to grant.

As I said, however, the term “subsidiarity” has a legitimate use, describing a form of organization recommended by the social doctrine of the Catholic Church and elevated to a principle of government in a papal encyclical of Pius XI in 1931. From this source it was appropriated by Wilhelm Röpke, in his effort to develop a social and political theory in which the. Market economy would be reconciled with local community and the “little platoon” [cf. Röpke, The Humane Economy, tr. Elizabeth Henderson, Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1960]. What Röpke meant, and what Catholic doctrine implied, was very different from anything that could be expressed in Eurospeak. Subsidiarity, in Röpke’s understanding of the term, refers to the absolute right of local communities to take decisions for themselves, including the decision to surrender the matter to a larger forum. Subsidiarity places an absolute brake upon centralizing powers, by permitting their involvement only when requested. In Eurospeak, however, “subsidiarity” has the opposite sense, to expropriate whatever powers they might deem to be theirs. By purporting to grant powers in the very word that removes them, the EU constitution wraps the whole idea of decentralized government in mystery. A similar mystery is enshrined in such words as “proportionality,” “solidarity,” “ever closer union” and “acquis communautaire”: words and phrases which suggest a popular process of lawful gain, but whose real meaning is loss. To say that a power has become part of the acquis communautaire, for example, is not to say that it has been acquired by anything, or is henceforth to be exercised by any accountable body. It is to say that it has been lost in the bureaucratic labyrinth, so that nobody henceforth will really know how it is deployed, or how to rectify the abuse of it.

Just as Newspeak describes an embattled world, in which the forces of progress are constantly called upon to defeat the malignant “isms” that threaten them—capitalism, imperialism, left deviationism and so on—so does Eurospeak fill the world with its own brand of dangerous “isms,” abstract forces which are also mysteries at least as unfathomable as the “ever closer union” that they threaten. Chief of these mysterious “isms” is the “racism and xenophobia” against which we are warned by the Commission in one after another of its official pronouncements and directives, and which has now been made into a crime. Nobody knows what this crime involves—and that is the real purpose of the label, namely, to instill in the public mind the idea of a malign force that stalks through all European society, inhabiting the hearts and brains of people who may not be aware of its machinations, diverting even the most innocent project on to the path of sin. My own very English patriotism might be proof of guild; in declaring myself the enemy of Eurospeak it is possible that I am exhibiting xenophobia; my Anglo-Saxon culture could very well convict me of racism. Or maybe not. How am I to know? The important point is that I am not to know. I am to remain baffled by the mysterious possibility of my own criminal frame of mind, so as to learn not to question the wise decrees by which I am henceforth to be governed. Racism and xenophobia are strictly thought-crimes, of the kind described by Orwell.

*Excerpted from chapter 9, “Newspeak and Eurospeak” in A Political Philosophy: Arguments for Conservatism

(London: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2006), 161-166 of 161-175. Available for purchase at Eighth Day Books. Learn more about Sir Roger Scruton here at his website.