Inaugural Florovsky Lecture: On Memory, Hope & Cultural Renewal

Inaugural Eighth Day Florovsky Lecture

by Erin Doom

Feast of the 45 Holy Martyrs of NikopolisAnno Domini 2018, July 10

…that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in Us, that the world may believe that You sent Me . ~John 17.21

In January of 2015 the noted author James K. A. Smith visited Wichita as the keynote speaker for our fifth annual Eighth Day Symposium. Around a year after that visit he reached out to me for an interview to be published in Comment Magazine, an excellent like-minded journal he edited at that time. Here’s what the introduction to that interview had to say:

When Comment editor Jamie Smith visited Eighth Day Institute last year, he was astonished by a hidden gem tucked away in Wichita. Like a metaphysical wardrobe in the heart of “flyover” country, the Eighth Day Institute is a portal to another world—a place where remembrance is at the heart of cultural renewal. His experience at EDI gave him hope for the future of faith.

“A place where remembrance is at the heart of cultural renewal.”

“Hope for the future of faith.”

I want to use those two phrases as bookends to this inaugural Eighth Day Florovsky Lecture. (I preface Florovsky Lecture with Eighth Day intentionally because we’re not the first to present a Florovsky Lecture; the Orthodox Theological Society of America also organizes one at its annual meeting.) But I also want to weave the theme of cultural renewal through the lecture, since that is the mission of Eighth Day Institute.

We’re going to do five things this evening. (1) We’ll begin with remembrance and then (2) we’ll remember Fr. Matthew Baker, to whom this lecture and this Florovsky Week is dedicated. Next (3), I’ll briefly introduce you to Florovsky, then (4) we’ll hear from Florovsky himself, by means of an imaginative exercise that we do at every Hall of Men and Sisters of Sophia by answering one simple question: what would Florovsky have to say to us today, in the 21st century, right here in Wichita, KS, if he were to descend from the cloud of witnesses and give us a word about cultural renewal? Finally (5), we’ll end with hope.

So first, remembrance. I believe Jamie is right. Remembrance is at the heart of cultural renewal. That’s why it is at the heart of everything we do at Eighth Day Institute where our mission is to renew culture. That’s why we are gathering here this evening, to remember the life of Fr. Georges Florovsky. That’s why the Eighth Day Symposium banquet celebrates an early Christian saint each January: St Gregory the Theologian (2013), St Anthony the Great (2014), St Athanasius the Great (2015), St Cyril of Alexandria (2016), St Gregory of Nyssa (2017), and St Basil the Great (2018). At the next Symposium in 2019 we’ll be remembering the life of St. Mary of Egypt…she has a fascinating story…you really should come and learn about her! It’s also why the Hall of Men celebrates two heroes a month and the Sisters of Sophia remember a heroine each month. It’s why you have a pint glass with Florovsky on it, and it’s why we have lots of other pint glasses in the back with various other saints and heroes on them. It’s why we have an annual Inklings Oktoberfest, to remember a small group of friends—especially C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien—who spurred one another on to write stories and essays that have had unimaginable influence on so many people around the world, including Warren Farha who created this whole Eighth Day enterprise when he opened Eighth Day Books. [How about a toast to Warren! To the proprietor of Eighth Day Books, a peddler of books and culture!] Remembrance is why we’ve started this new event with such a strange name: Florovsky Week. While the focus this evening is on Florovsky himself, the emphasis for the week is to remember the common heritage we all share in the first millennium of Christian history. We want to remember that common tradition as a way to overcome our divisions, in this instance as a way to deal with one of the key theological issues that divided Christians during the Reformation period: justification by faith alone.

Remembrance is central to the work of Eighth Day Institute because it is central to the life of the Church. As Christians we remember the birth of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ every December. We remember His death, burial, and resurrection, every Easter—or Pascha, as the Orthodox Tradition calls it. Every year we remember the Ascension forty days after the Resurrection and then Pentecost ten days later to remember the descent of the Holy Spirit. And we remember the saints, just as St. Paul does in the Epistle to the Hebrews in his famous chapter on faith; just as the early Christians did when they celebrated the death day of the martyrs as their true birthday, for it was on the day of their martyrdom, the day they bore witness to their Savior, that they were born into the kingdom of God and became fully alive. Today the Church’s calendar is filled with saints to remember, usually multiple saints on each day. Today, for example, we remember the 45 Holy Martyrs of Nikopolis—they were burnt alive in the year 315 under the Roman Emperor Licinius. Had you heard of them before tonight? They are a part of the great cloud of witnesses and we should know them.

Now, what does all this talk about remembrance have to do with cultural renewal? Why do I think Jamie is right to say that remembrance is at the heart of cultural renewal? In order to answer that question, I'd like to introduce you to a couple other heroes of mine. First the Catholic historian Christopher Dawson, who I met simultaneously with Florovsky while reading THIS book on historiography for my Master’s degree at Wichita State University (C. T. McIntire, ed., God, History and Historians: Modern Christian Views of History , 1977). I’d like you to listen to what Dawson has to say about culture:

Culture is like a city that has been built up laboriously by the work of successive generations, not a jungle which has grown up spontaneously by the blind pressure of natural forces. It is the essence of culture that it is communicated and acquired, and although it is inherited by one generation from another, it is a social not a biological inheritance, a tradition of learning, an accumulated capital of knowledge and a community of ‘folkways’ into which the individual has to be initiated.

Hence it is clear that culture is inseparable from education, since education in the widest sense of the word is what the anthropologists term ‘enculturation’, i.e., the process by which culture is handed on [traditioned, we could say, since the Greek word for tradition, paradosis, simply means to hand down] by the society and acquired by the individual. […] A common educational tradition creates a common world of thought with common moral and intellectual values and a common inheritance of knowledge, and these are the conditions which make a culture conscious of its identity and give it a common memory and a common past. Consequently any break in the continuity of the educational tradition involves a corresponding break in the continuity of the culture. If the break were a complete one, it would be far more revolutionary than any political or economic change, since it would mean the death of the civilization. (Dawson, Crisis of Western Education , 3-5)

There are five key ideas to be gleaned from this passage; or we can frame them as five questions that can be answered:

1) What is culture? Culture is something that is built; it is created. And it takes a great deal of work. It is a laborious enterprise. It is a podvig – that’s a Russian word Florovsky uses frequently: an ascetic exploit. Building or creating culture is a prominent theme in the work of Florovsky.

2) But what is actually built? A social inheritance, a tradition of learning into which the members of a society must be initiated.

3) Where are the members of society initiated? In the church and in the family. It’s the church’s responsibility to pass the faith on to the family. And it is the responsibility of the parents to pass that faith on to their children. That means the church and families—YOU! —have an educational responsibility, a catechetical duty (to slip in a word that is in my original dream for EDI: the catechetical academy – you can read about that dream in the first issue of Synaxis).

4) Now, what does that tradition of learning—of catechesis—actually do? According to Dawson, it “creates a common world of thought with common moral and intellectual values and a common inheritance of knowledge.” It gives the culture a common vocabulary, a common MEMORY. Do we still have this? Look around and I think the answer is pretty obvious. We’ve lost it. And it’s why our culture is in chaos.

5) What happens when the labor of passing on that tradition of learning is broken? I don’t think Dawson is overstating his case to suggest that a complete break “would be far more revolutionary than any political or economic change…” Why? because “it would mean the death of the civilization.”

Has our civilization died? Is that what I’m insinuating? No. At least not yet. But we have broken the tradition of learning. We have forgotten. We have failed to do the laborious work of preserving what was handed down through so many generations. And so I do believe that we—western civilization, that is—are on the path toward death. It’s why I’m so passionate about my work at Eighth Day Institute. It’s also why I’m encouraged by the rise of classical schools, schools like Christ the Savior Academy and Wichita Classical School, to just mention two in Wichita.

Now for one more sidetrack. In this same book with Dawson and Florovksy, I also met T. S. Eliot. And then later I read THIS important book: Christianity and Culture. It consists of two pieces, one based on lectures he delivered in 1939 at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge: “The Idea of a Christian Society”; and the other based on three pieces he published in 1945-46: “Notes towards the Definition of Culture.” In “The Idea of a Christian Society,” Eliot distinguishes three historical periods for Christians:

- When “Christians are a new minority in a society of pagan traditions.” Done!

- When “the whole society can be called Christian.” Been there!

- When “practicing Christians are a minority in a society which has ceased to be Christian” (p. 9). Is this where we are?

Eliot asked this in 1939 and he ultimately answered no, based on the second of two criteria. Here are his critieria:

- “A society has ceased to be Christian when religious practices have been abandoned, when behavior ceases to be regulated by reference to Christian principle, and when in effect prosperity in this world for the individual or for the group has become the sole conscious aim.” Sounds like us today.

- “A society has not ceased to be Christian until it has become positively something else.”

Now here is where I think Eliot’s question of whether or not Christians are a minority can be answered in the affirmative today. Our culture has positively become something else. And I would argue in at least two ways. First, following the argument of Charles Taylor’s magisterial book A Secular Age, we have constructed a secular age, by which Taylor means an age in which there are many options, more so than ever before, an age in which Christianity is the most difficult option because belief in God is no longer axiomatic, no longer built into the structures of existence the way it was in the middle ages. Now that’s a far too simplified version of that 800-page book, but it will have to do for now, given our time restraints. The second way our society has become something other than Christian has been described in Mario Vargas Llosa’s book Notes on the Death of Culture—a direct play on Eliot’s essay “Notes towards the Definition of Culture”—in which he describes our society as a civilization of the spectacle. Listen to Llosa’s description:

What do we mean by civilization of the spectacle? The civilization of a world in which pride of place, in terms of a scale of values, is given to entertainment, and where having a good time, escaping boredom, is the universal passion. To have this goal in life is perfectly legitimate, of course. Only a Puritan fanatic could reproach members of a society wanting to find relaxation, fun and amusement in lives that are often circumscribed by depressing and sometimes soul-destroying routine. But converting this natural propensity for enjoying oneself into a supreme value has unexpected consequences: it leads to culture becoming banal, frivolity becoming widespread and, in the field of news coverage, it leads to the spread of irresponsible journalism based on gossip and scandal. […] The culture in which we live does not favor, but rather discourages, the indefatigable efforts that produce works that require of the readers an intellectual concentration almost as great as that of their writers. Today’s readers require easy books that entertain them and this demand creates a pressure that becomes a powerful incentive to writers. [the same can be said about lectures…keep it under 20 min…sorry, not this one!] […] A notable feature of contemporary society is the waning in importance of intellectuals who, for centuries, up until recently, had played a significant role in the life of nations. . . .Today, intellectuals have disappeared from public debates, at least the debates that matter. . . . . Because in the civilization of the spectacle, intellectuals are of interest only if they play the fashion game and become clowns. [Our] culture favors minimal intellectual effort, at the expense of commitment, concern and, in the final instance, even of thought itself. This culture has given itself over, in a passive manner, to what a critic now relegated to obscurity [not at Eighth Day Books!]—Marshall McLuhan—who was a wise prophet of the cultural signs of our times—called the ‘image bath’, a form of docile submission to emotions and sensations triggered by an unusual and at times very brilliant bombardment of images that capture our attention, though they dull our sensibilities and intelligence due to their primary and transitory nature.

Does this sound familiar to you? It does to me. Our culture has been taken captive by the spectacle; or I should say we have willingly submitted to the rule of the spectacle. We might even put it in the words of the title to a wonderful book by the social critic Neil Postman: We are Amusing Ourselves to Death. Franklin Sanders, a farmer-economist friend in Dogwood Mudhole, TN once called it Americanity, which he suggested consists of the twin pillars of individualism and greed. I need not say more, except that I would argue that many Americans who call themselves Christians are just as captive to this new global culture that is smitten by the gods of entertainment, comfort, and convenience. Taking up the cross and dying to self is not on their agenda. All that to say that I think Eliot would agree that today we do indeed fit into his third historical era of the post-Christian.

Eliot goes on to conclude his reflection on the state of his culture with these words: “I believe that the choice before us is between the formation of a new Christian culture, and the acceptance of a pagan one” (9-10). That choice is all the more pressing to us: will we form a new Christian culture? Do we have the strength, the stamina, the will to build or create a new Christian culture? Are we willing to put in the time and labor necessary for rebuilding a tradition of learning that will give us “common moral and intellectual values,” a “common inheritance of knowledge,” a common vocabulary, a common MEMORY?

There. That’s my long rant on remembrance and cultural renewal. I had to do it. It’s what I’ve dedicated my life to. But we are here to learn about Florovsky. Before turning to Florovsky, however, I do want to formally dedicate this lecture and this week, and for that matter, the work of Eighth Day Institute, to the memory of Fr. Matthew Baker. I’ve already told the story of Fr. Matthew’s tragic death in my note in your program [Click here for program and see pp. 2-3]. Please do read it. All I will say right now is that, even though I never met him in person, I still consider Fr. Matthew a dear friend. This is how the communion of saints works.

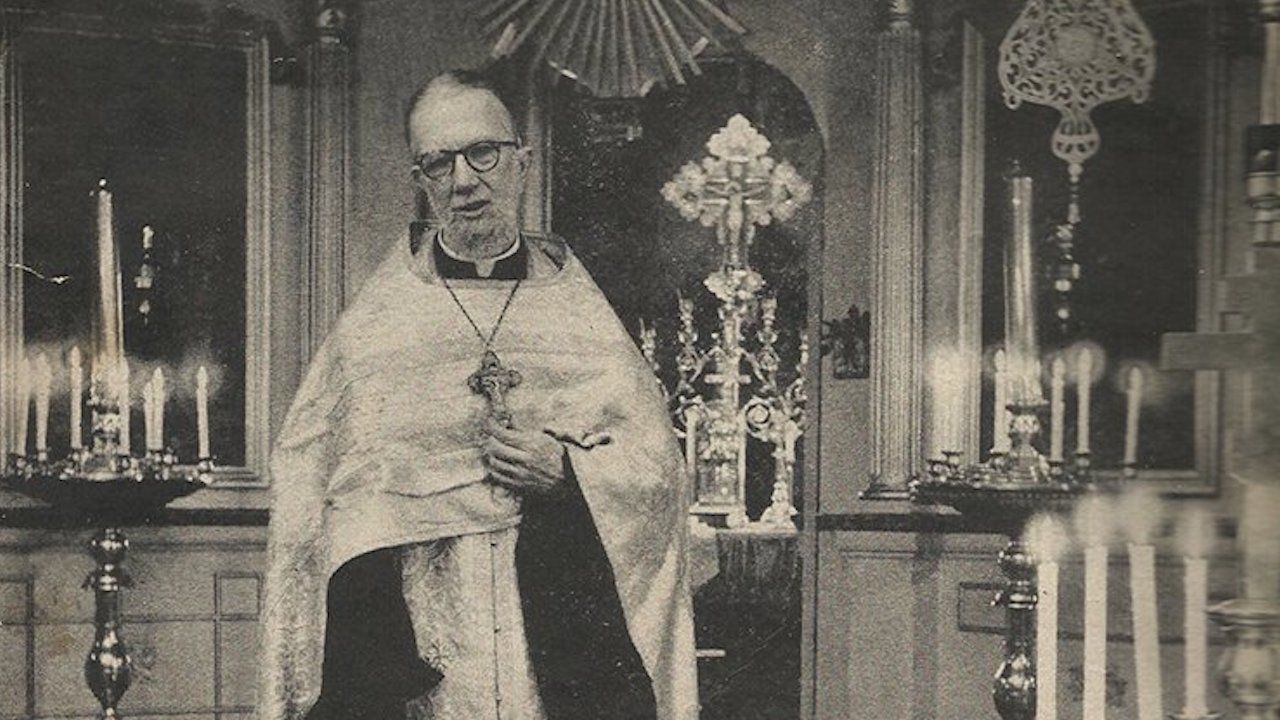

Fr Matthew was the driving force behind the Florovsky Symposium, which began the same year we launched the Eighth Day Symposium in 2011. I coordinated a live feed broadcast of all four of those symposia from Princeton University to Wichita, KS. Without ever meeting him in person, I felt like I knew a man who had drunk deeply from the well of the Fathers...and of Florovsky; a man who, under the influence of Florovsky, understood my passion for pursuing the unity of Christians, a passion that was born in me when I worked in Mexico and experienced a Baptist church divide three times over the course of two months. Many predicted Fr. Matthew would be the most important theologian of the 21st century, just as many have called Florovsky the most important theologian of the 20th century. His loss is truly tragic. It really does break my heart. So, to organize this evening, this inaugural Florovsky Week, is truly an honor for me because I see it as a continuation of his work. As I note in the program, this week we humbly stand on the shoulders of two giants: Fr. Georges Florovsky and Fr. Matthew Baker. May their memory be eternal!

Now I have to

present you Florovsky now, and I only have about ten minutes left for the rest

of this lecture! How in the world can I do Florovsky justice? I vividly remember

Fr. Matthew’s lecture at the first Florovsky Symposium. It was way longer than

he had time to present. He had so much to say, too much to say. It was an

impossible situation for him. I felt his pain then. And I feel exactly the same

way today. There is so much to say about Florovsky. But alas, I’ve promised 30 minutes and I intend to honor that. So let me simply share a few memories and explain how

Florovsky has a mission, or maybe better put, a message for our secular age.

I’ve already mentioned my first encounter with Florovsky while studying history at WSU. My next memory is my reception into the Orthodox Church. My friend, and an original Eighth Day Institute board member, Carol Adamson, gave me THIS book, volume 3 in the 14-volume collected works of Florovsky. She also included a passage by Fr. Thomas Hopko—this passage! Little did I know back then in 2004 how significant this gift would be, how much the author of this book would shape my life. Thank you, Carol, for this amazing gift! And then I remember receiving a draft of Fr. Matthew Baker’s Master’s thesis on Florovsky— THIS draft. I had already read quite a bit of Florovsky, but this thesis rocked my world. For the first time I realized how important ecumenical dialogue was to Fr. Georges, how central it was to his key proposal that I’ll touch on in a moment. And I was moved to dig far deeper into his work, reading every book review he ever wrote, searching for every rare and obscure writing I could find. And I’ve been hooked ever since.

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has described Florovsky as “the greatest Russian, and indeed Orthodox, theologian during the twentieth century.” Rowan Williams says “his name deserves to stand with those of the major theologians of the [20th] century.” Andrew Louth says “he was the most famous Orthodox theologian in the world” when he died on August 11, 1979, mostly due to his huge involvement with the World Council of Churches—he was one of its fourteen founding members. The recently canonized Serbian theologian St. Justin Popovich describes Florovsky as “an icon on the deisis of Orthodox theology.” The accolades go on and on. The problem is that, as famous as he may have been at one time, he is little known and hardly read at all today, outside of a very small group of scholars.

There are a few factors for this ignorance. For one thing, he only wrote three books: The Ways of Russian Theology and two volumes of Patristics lectures. But if you take into consideration his occasional articles, his sermons, his letters, his book reviews, his editorials—he launched St Vladimir’s Seminary Quarterly—then you begin to assemble a massive body of work. Not counting the archives at Princeton University, St Vladimir's Seminary, and those in the possession of Katherine Baker, a compilation of his writings includes 376 published pieces. Another significant factor is that, although many of these writings were published in the 14-volume collected works, they have been out of print for many years now. And most people who own them do not ever let them go. There is a new volume coming out from Oxford with a sampling of his essays, but I'm sure it will be expensive and inaccessible to most people. But I am slowly posting his writings in a Florovsky Archive on the Eighth Day Institute website, trying to make them more available to the wider public, or at least to Eighth Day Members. Plus, you have one of them in your program, which is a personal description of his experience with ecumenical dialogues. I hope you’ll read it here (see pp. 4-7).

So what was his message? It was a message of remembrance and hope. It is most famously known as a proposal called the "neopatristic synthesis." And it is usually simply and inadequately defined as a call for a return to the Fathers. It is that, indeed. But it is so much more. In my dissertation, I clarify it with ten different characteristics. I won’t bore you with those this evening. But I will say that, for our purposes this evening and this week, it can be boiled down to a call for a return to the common heritage of all Christians in the first millennium as a way to overcome division. Florovsky believed all Christians could find a common vocabulary for a common idiom in the Bible and in the Fathers of those first thousand years of the Church’s history. He believed the early Christians baptized Hellenism and thereby built a Christian culture. Does that sound familiar? Building culture. Common vocabulary. The neopatristic synthesis was at heart an ecumenical proposal, a call for Christians to create a new Christian culture, and in doing so, to overcome the divisions of the second millennium of the Church’s history. This is his message for us today.

Now let me begin winding down by answering the key question proposed at every Hall of Men and Sisters of Sophia meeting. What would Florovsky say to us about cultural renewal? I’ve boiled his answer down to twelve words:

1. Remember! We’ve covered that one!

2. Repent! More than anything he’d beg us to feel the pain of our division and ask us to repent, to repent of our apathy toward our disunity, to repent of our sin of disunity.

3. Study! He’d tell us we all have a duty to learn. He frequently cited an early Christian heresy called Apollinarianism which denied Christ a human mind. For Florovsky, as for the Church, Christ became fully human, which means that he assumed a fully human mind. God has thus redeemed the human mind. Moreover, we are all disciples of Christ, Florovsky was fond of reminding people, which means we are His students, we are His apprentices, His learners. He has given us amazing minds for an eternal quest of learning under His tutorship. It’s our responsibility to use them. This is why I believe an “academic” conference fits within Eighth Day Institute’s mission of renewing culture.

4. Confront! This comes up repeatedly throughout Florovsky’s writings. It’s in the essay in your program. He insisted that we must not minimize our differences. We must courageously confront them so that we can actually overcome them, instead of pretending they don’t exist. How does ignoring problems in your family work for you? It doesn’t. You have to actually deal with them. This is why the Florovsky Week intends to tackle a dividing issue head on every year. Next year it will be “The Patristic View of Church Authority: Bible, Pope, or Conciliarity?" But it’s not just a confrontation.

5. Encounter! Look into each other’s eyes. Listen to one another. Listening is a lost art. We must relearn it. It’s necessary for this sort of ecumenical enterprise. Listen to one another so that you can understand one another, not so that you can come up with a winning argument to defeat an opponent. We are brothers and sisters in Christ, not enemies!

6. Be humble! Please do not think you understand it all, that you have all of the answers. Listening requires humility, a willingness to believe you can actually learn something from the other person. We can ALL learn from one another. So be humble, listen, and learn!

7. Be patient! Flovovsky repeatedly talks about a patient ecumenism, about the sin of ecumenical hastiness. This is a long-term project. This reminds me of another passage from T. S. Eliot: “The fact that a problem will certainly take a long time to solve, and that it will demand the attention of many minds for several generations, is no justification for postponing the study.” We can’t avoid our divisions and we can’t rush solutions. We must be patient and prepared for the long-haul.

8. Work! Work hard! Division exists because of human decisions, Florovsky tells us. Reunion is only possible with more human decisions. We must decide that union is important. We must decide to take action. We must decide to work toward overcoming the division. We must decide to engage in a dialogue of love and truth.

9. Trust in the Lord! We have our role to play. But ultimately, it is in God’s hands. As Florovsky puts it, “the advance is in the hands of the Lord.”

10. Have Hope! I am convinced that there has never been a moment in history like today. There has never been another civilization that did not have religion at the center of its culture. There has never been a global entertainment culture, transmitted around the entire world, first through radio waves, then the TV, and now through movies and the internet. This can be a frightening thought. But Florovsky would echo Christ: “Take heart. Be not afraid. Have hope.” Florovsky believed history is shaped by human decisions. Our decisions today do indeed have the power to change the course of history. A new Christian culture can be built. A tradition of learning can be revived. A common vocabulary can be acquired. But it’s going to take a lot of work. And it’s going to take Christ’s blessing, which leads to the eleventh word.

11. Christ! First and foremost, look to Christ! Much of Florovsky’s work focused on Christology. He always kept Christ at the center of his work. It’s why we have this Gospel book displayed here in the front. This is a new thing for us at Eighth Day Institute. And it’s because of Florovsky. Listen to this passage from him on the ecumenical councils:

The Ecumenical Councils functioned in an age of absolute despotism more like a forerunner of representative government than like an elite, aristocratic group, cowed by and servile to the imperial and secular State. The procedures used in the meetings of the Ecumenical Councils in fact sanctioned the principle of discussion, the principle of common and open deliberation as the best means of arriving at an expression of the truth of the faith and settling controversies.

With so much controversy over who presided at the Ecumenical Councils [i.e., Emperors], with so much written on the subject, one reality is often lost, neglected, or forgotten. In the middle of the assembled clergy something special lay upon a desk or table. That something special held a special place and had a special significance at all councils. On that desk or table lay an open copy of the Gospels. It was there not only as a symbol but also as a reminder of the real presence of Christ in accordance with his promise that where two or three are gathered together in his name, he will be present. In a very real sense it was the presence of the open Gospel which presided. Christ is the Truth. The source and the criterion of the truth of Christianity is the Divine Revelation, in both the apostolic deposit and in the Holy Scriptures. (Florovsky, “Nicaea and the Ecumenical Council” in Collected Works VIII, 137).

We are heeding this first piece of advice, beginning tonight, and at every other Eighth Day event. Christ is with us because we are gathered in His name. And it is His presence in THIS Gospel which has been and shall continue to preside over this evening, over the following days as we engage in a dialogue of love and truth, and over all future EDI events.

12.Finally, Pray! Our hope is based on the contingent nature of history, on the freedom of the human person to make decisions, on the person and presence of Christ, and on the power of prayer.

And that’s how I want to end. I’d like to invite you to join me in praying Christ’s prayer for unity on a regular basis. We do this at every Hall of Men and Sisters of Sophia meeting. And we’re going to close this evening by doing it here. Please stand with me as we pray Christ’s prayer for unity in John 17.

PRAY JOHN 17

The final word:

- If you believe the laborious work of building a tradition of learning is important,

- If you are committed to creating a new Christian culture,

- If you believe the divisions among Christians are a disgrace to the world around us,

- And if you believe endeavors like this one have an important role in overcoming those divisions and in facilitating the laborious work of building a common tradition,

- Then, please consider making a sacrificial offering to Eighth Day Institute [and I'll automatically register you for the 2020 Florovsky Newman Week on June 3-6].

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.