A most important path to the discovery of duty is also the study of the divinely-inspired Scriptures. For in them are not only found the precepts of conduct, but also the lives of saintly men, recorded and handed down to us, lie before us like living images of God’s government, for our imitation of their good works. And so in whatever respect each one perceives himself deficient, if he devote himself to such imitation, he will discover there, as in the shop of a public physician, the specific remedy for his infirmity. The lover of chastity constantly peruses the story of Joseph, and from him learns what chaste conduct is, finding Joseph not only continent as regards carnal pleasures but also habitually inclined towards virtue. Fortitude he learns from Job, who, when the conditions of his life were reversed and he became in a moment of time poor instead of rich and childless when he had been blessed with fair children, remained the same, and always preserved his proud spirit unhumbled; nay, even when his friends who came to comfort him trampled upon him and helped to make his sorrow more grievous, he was not provoked to wrath. Again, if one considers how he may be at once meek and high-tempered, showing temper against sin, but meekness towards men, he will find David noble in the valiant exploits of war, but meek and dispassionate in the matter of requiting his enemies. Such too was Moses, who rose up in great wrath to oppose those who sinned against God, but endured with meekness of spirit all slanders against himself. And in general, just as painters in working from models constantly gaze at their exemplar and thus strive to transfer the expression of the original to their own artistry, so too he who is anxious to make himself perfect in all the kinds of virtue must gaze upon the lives of the saints as upon statues, so to speak, that move and act, and must make their excellence his own by imitation.

Prayer, again, following such reading finds the soul, stirred by yearning towards God, fresher and more vigorous. Prayer is to be commended, for it engenders in the soul a distinct conception of God. And the indwelling of God in this—to hold God ever in memory, His shrine established within us. We thus become temples of God whenever earthly cares cease to interrupt the continuity of our memory of Him, whenever unforeseen passions cease to disturb our minds, and the lover of God, escaping them all, retires to God, driving out the passions which tempt him to incontinence, and abides in the practices which conduce to virtue.

And, first of all, one should take heed not to be boorish in conversation, but to ask questions without contentiousness, and answer without self-display; neither interrupting the speaker when he is saying something useful, nor being eager to interject his own words for the sake of ostentation, but observing moderation both in speaking and in listening. One should not be ashamed to learn, nor should he grudge to teach; and if one has learned something from another, one should not conceal the fact, as degraded wives practice concealment when they palm off bastard children as their own, but one should candidly acknowledge the father of his idea. The middle tone of voice is preferred, neither so soft as to elude the ears, nor so loud and strong as to be vulgar. One should first reflect upon what one is going to say, and then deliver one’s speech. One should be affable in conversation and agreeable in social intercourse, not resorting to wit as a means of gaining popularity, but depending upon the charm which comes from gracious politeness. On all occasions abjure asperity, even when it is necessary to administer a rebuke; for if you first abase yourself and show humility, you will easily find your way to the heart of him who needs your ministration. We also frequently find useful the method of rebuke employed by the prophet, who did not of himself set a definite penalty on David when he sinned, but employed a fictitious character and constituted David judge of his own sin; so David first pronounced judgment against himself, and after that could not find any fault with his censor.

The humble and abject spirit is attended by a gloomy and downcast eye, neglected appearance, unkempt hair, and dirty clothes; consequently the characteristics which mourners effect designedly are found in us as a matter of course. The tunic should be drawn close to the body by a girdle; but let the belt not be above the flank, for that is effeminate, nor loose, so as to let the tunic slip through, for that is slovenly; and the stride should be neither sluggish, which would argue a laxity of mind, nor, on the other hand, brisk and swaggering, which would indicate that its impulses were rash. As for dress, its sole object is to be a covering for the flesh adequate for winter and summer. And let neither brilliancy of color be sought, nor delicacy and softness of material; for seeking after bright colors in clothing is on a parity with women’s practice of beautifying themselves by tinting their cheeks and dyeing their hair with artificial luster. However, the tunic ought to be of such thickness that it will require no auxiliary garment to keep the wearer warm. The sandal should be inexpensive, yet completely adequate to one’s needs.

And in general, just as one should consider practical utility in the matter of clothing, so too, in the matter of food, bread will satisfy actual needs, water will cure the thirst, if one his healthy, and there are besides all dishes of vegetables and fruits that help to preserve the body’s strength for inevitable needs. And one should not exhibit frantic gluttony in eating, but on all occasions should preserve composure, gentleness, and restraint as regards the pleasures of the palate. And not even at table should one allow the mind to be unoccupied with thoughts of God, but one should make the very nature of the food and the structure of the body that receives it an occasion for His glorification. What varied forms of nutriment suited to the peculiarity of bodies have been conceived by Him who dispenseth all things! Before meals let prayers be said worthy of the bounties which God both gives now and has stored up for the future. After meals let prayers be said that include thanksgiving for the gifts received, and petitions for those promised. Let one hour, the same regularly each day, be set aside for food, so that out of the twenty-four hours of day and night, barely shall this one be expended on the body, the ascetic devoting the remainder to the activities of the mind.

Sleep should be light and easily broken, such as naturally follows a moderate diet; and it should be interrupted deliberately by meditations on high themes. For to be overcome by heavy torpor, in which the limbs are relaxed and play is given to foolish fantasies, causes those who sleep in this fashion to experience a daily death. On the contrary, what is cock-crow for the rest of men is midnight for the practicers of piety, when the quiet of night grants most leisure to the soul, when neither the eyes nor the ears conduct harmful sounds or sights to the heart, but the mind alone with itself communes with God, corrects itself through the recollection of past sins, sets up its barriers to ward off evil, and seeks God’s aid for the consummation of its longings.

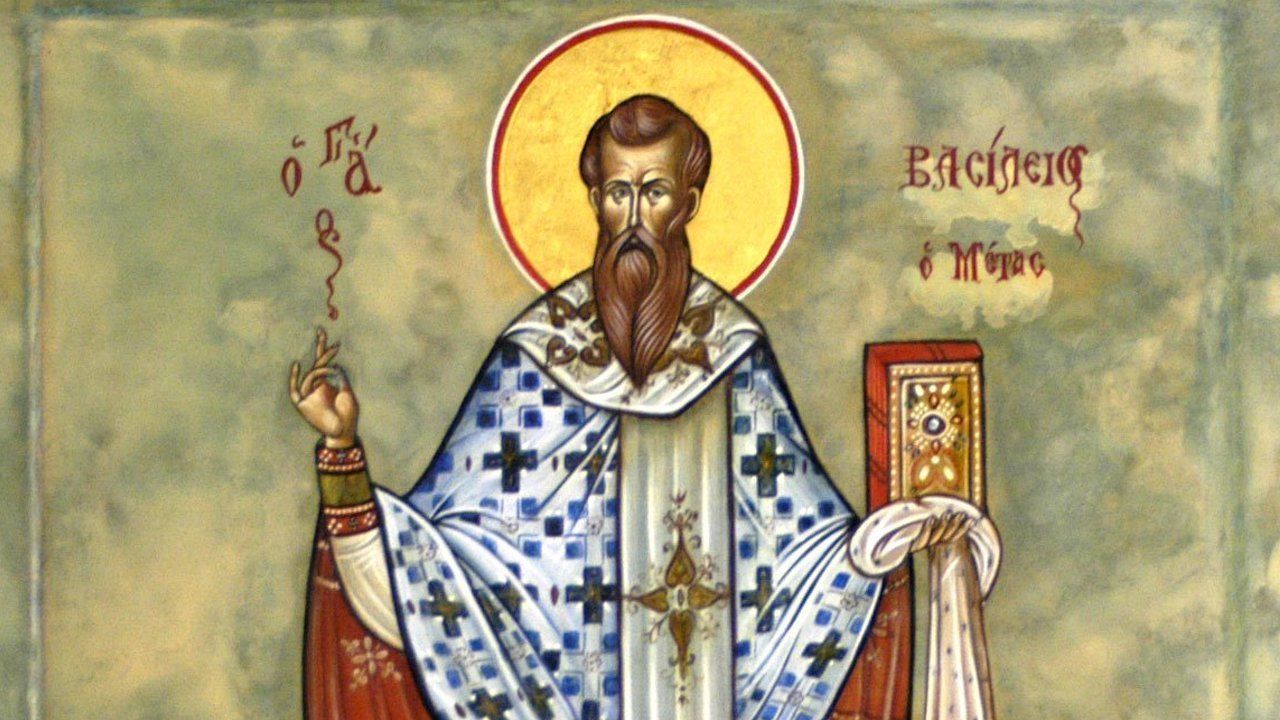

~St Basil, Letter 2 to St Gregory Nazianzus