WE NOW

enter the most sacred week of the year. It starts with the feast of Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem, which, as we have already said, taken with the raising of Lazarus, forms a prelude of joy and glory to the harrowing humiliations which are to follow. The Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday of Holy Week are a preparation for the Passion. They already have a strongly accented character of mourning and repentance. The Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of Holy Week belong to the paschal solemnities – each one of these days reveals to us a special aspect of the mystery of Easter. One could even say that this mystery has three aspects, each of which corresponds to a day: Holy Thursday, Holy Friday, and Holy Saturday. One could also say that each of these three aspects corresponds to a place: the Upper Room, Golgotha, the Holy Sepulchre. Holy Thursday commemorates the mystery of the upper room, Holy Friday the mystery of Golgotha, Holy Saturday the mystery of the tomb of Christ. On the Thursday, in the upper room, Jesus, through a sacramental action, both announces and represents, consecrates and offers what is to take place during the following days. On the Friday, at Golgotha, Jesus, by His death on the Cross, accomplishes our redemption. On the Saturday, Jesus rests in the tomb; but the Church, already looking ahead to the feast of Easter Sunday, speaks to us of the victory over death that our Savior has won. This anticipation of the Resurrection on Holy Saturday allows us to say that the mystery of Christ’s Resurrection, triumphantly celebrated on Easter Sunday, already belongs, although incompletely, to Holy Week. And so this week constitutes a summary of the whole economy of our salvation.

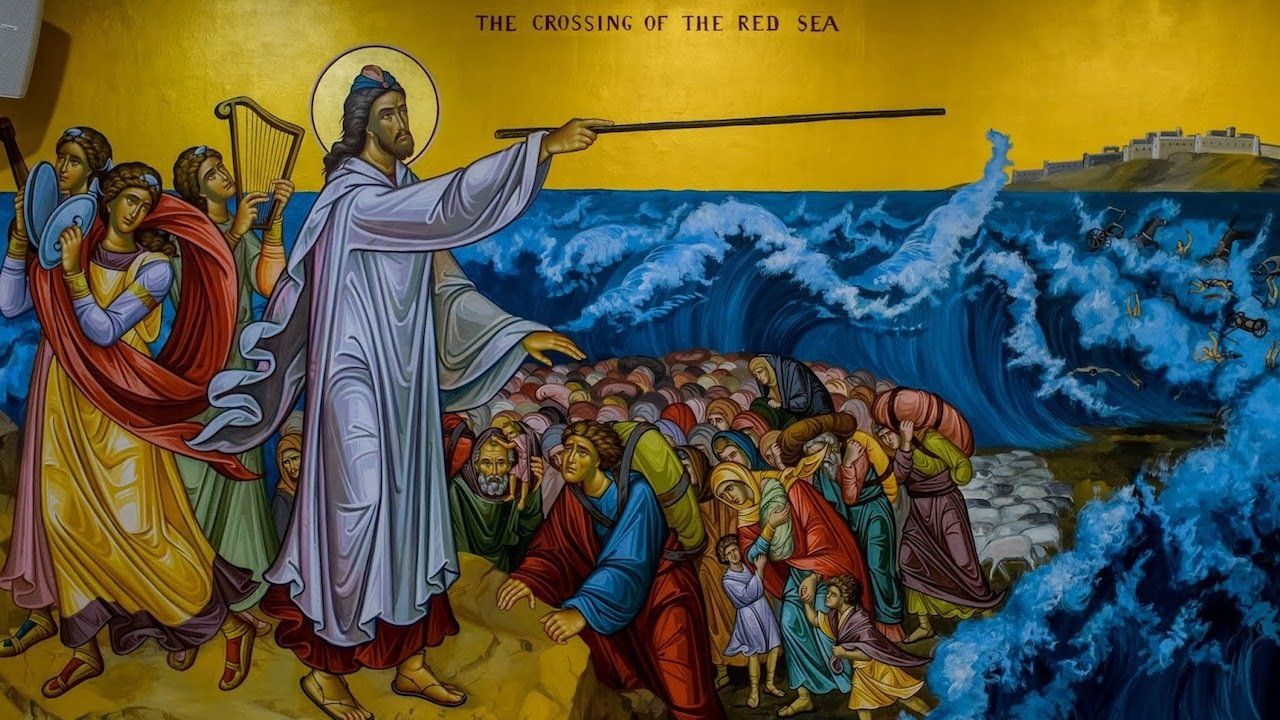

It would be a great mistake to want to concentrate on one of the aspects of the paschal mystery by separating it from the others. The word “Passover,” in the traditional language of the Church, does not only designate the Sunday of the Resurrection, it also covers the mystery of the eucharist, the mystery of the Cross, and the mystery of the empty tomb. Holy Thursday, Holy Friday, Holy Saturday, and, finally, the Sunday of Easter altogether make up one and the same unique paschal mystery. This whole unity is the Christian transposition of what the Jews call “the Passover,” that is to say, the passage. The elements of the Jewish mystery of the Passover correspond to those of our paschal mystery. For them, there is the feast in which the lamb is eaten. There is the blood of the lamb – the sign of salvation for those houses whose door was painted with it and whom the angel of death would spare. There is the crossing of the Red Sea – the departure from the land of Egypt and from slavery – the miraculously divided waters and the passage across on dry ground and, at last, the arrival on the other side, the side of freedom and hope. Holy Week will only have its true meaning for us when we see it as a “Passover,” a passage from death to life.

We have said that the time of Christmas and Epiphany in a way express the “first conversion” of the soul, the first manifestation of Jesus, His first meeting with us, and the beginning of the shared life of Master and disciple. The time of the Passion, or rather of the whole paschal mystery, express the “second conversion,” the confrontation of the disciple with the cross and the tomb of his Master. Now, no longer is it enough to follow Jesus along the roads of Galilee, along the paths of His earthly pilgrimage, and to abandon oneself to that very gentle intimacy of His friendship (an intimacy which our unfaithfulness has so often ruptured and which Jesus, nevertheless, is always ready to renew). Holy Week confronts us with the redemptive ministry or office of the Christ, rather than with His person. It offers us the objective grace and inner experience of salvation through the Christ. It sets before us and invites us to participate in the great realities: awareness of sin, repentance, the substitution of the Lamb of God for the sinner so that sin may be redeemed, the sacrifice of the Cross, and God’s acceptance of this sacrifice as it is revealed by the Resurrection. We are called to let the blood of Christ flow over our spiritual wounds, to unite ourselves to the sacrificial death of the Savior so that we may be united to His new life. Mors et Vita, death in Christ and life in Christ: such is the “second conversion”; this is the ordeal to which Holy Week invites us. We should not draw near to the mysteries of this week – which are the mysteries of Christ, but are also the mysteries of our own selves – without trembling, yet also with infinite trust. “God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son (Jn. 3:16) … Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life (Jn. 15:13).” O my Savior, grant that during this week I may come to know the profound significance of the Father’s gift of His only Son, of the gift of His own life made by the Son, and of that “greater love” which the paschal mystery reveals. Grant me to know, too, what to “lay down His life” and “greater love” implies for me.

*From The Year of the Grace of the Lord

by A Monk of the Easter Church (SVS 2001), 138-140.