ACCORDING

to the Old Testament, holiness is not attainable other than through separation. Yet, within both theology and the Church, a holy man is not only he who is distinct and unique, but he whose uniqueness is achieved

free from the anonymity of “individuality.” Because a person does not exist for himself alone – and here is the quintessence of hagiology – realization of one’s authentic self occurs through the communion of persons, that is, through

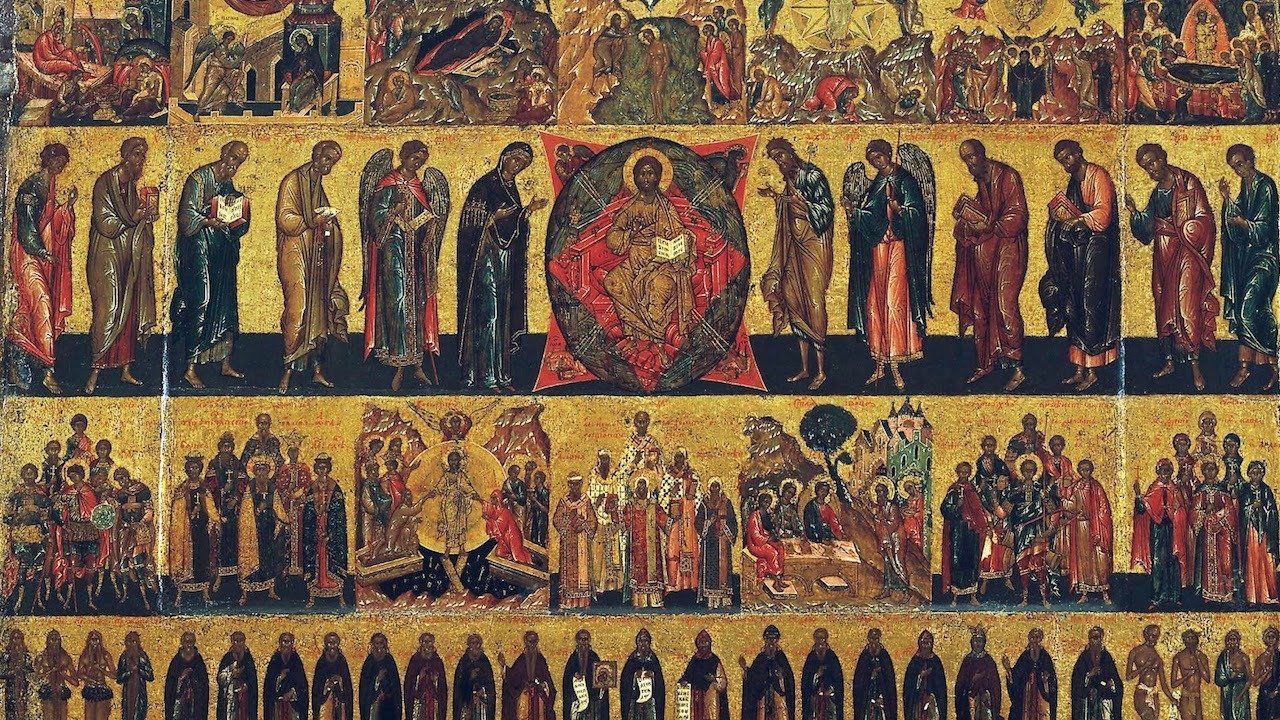

communio sanctorum

[communion of saints (or holy things)]. This is the reason why Church Tradition teaches that each saint is unique and distinct: his personal distinction is a result of a unique and irreplaceable relationship attained with the Unique and Irreplaceable Holy One. Importantly, this relationship takes place within the liturgical (common) experience of the Church. This Holy God bestows holiness, uniqueness and irreplaceability upon him. Here, it is important to emphasize how the call “Be holy…” (Lev. 19:1) requires one to love one’s neighbor as oneself (“love your neighbor as yourself; I am the Lord”; Lev. 19:18). Holiness requires a special kind of separateness that is inexplicably, but inevitably, connected to an experience with others.

Therefore, in view of the ethical and personal dimension of holiness, we can assert that the objective of every human being is not moral perfection through

holiness but uniqueness, that is, an otherness, manifested through communion with others. Here, one should point out that otherness and distinction – that is being different – are not the same. Distinctiveness can be expressed in terms of qualities that all share, but it does not apply to otherness because personal otherness and uniqueness exclude it. After all, in the Divine Liturgy the Church commemorates particular

saints and not saints as a general category. They are commemorated by their respective calendar dates: every individual ascetic and martyr. Only through their uniqueness and irreplaceability can they serve as inexhaustible sources of inspiration to Christians. Consider, for example: Abba Sisoe’s attitude toward death, Abba Anthony’s sober vigilance of the mystery of God’s judgments, holy Martyr Polycarp and other martyrs in their ekstatic passion during martyrdom for Christ, or the challenges of St. Simeon the Fool for Christ. They are all permanent and eternal examples of a sacrificial love “stronger than death.” At the same time, they pose an existential challenge to man. Perhaps a maximalistic anthropology stems from their hagiography, which at first glance seems unattainable for modern man and difficult for those who are used to a leisurely lifestyle. However, this kind of anthropology causes an awakening from a “dogmatic,” as well as from a likely ethical, “slumber.” After all, the higher one aims, the deeper one repents. The lives of the saints show that the search for holiness here

and now

turns man into a being who is unafraid of death and who leads all of creation into communion with the Holy God. The martyrs who offered themselves wholly to God serve as an example. Their being was united with God to such an extent that one can no longer speak of any separation

between them, although distinction

(i.e., otherness) certainly continues to exist and remains forever. The saints of the Church are those persons (the Theotokos, the Apostles, the marytrs and ascetics) who in one way or another, have overcome the anonymity of nature in their own and irreplaceable manner, and have united themselves with Christ, the “only Holy One” in a personal and unique way.

With a concept of holiness, we paradoxically arrive at the understanding of eschatology, and vice versa

as well. Namely, every saint is regarded as a future resident of Heaven, although in his lifetime he continues to bear both the marks of history, including the fall, and also man’s infirmities. Christ, however, retains the ultimate word. Were it not for the vision of the Eschaton, that is, were we not given a foretaste of the Kingdom in the Liturgy, of that ultimate communion with the saints, we would never know what is meant by either “holiness” or “holy man.” In other words, it is only the vision and the liturgical experience of the true, end state of the world that provides us with the possibility of knowing something about the true world, man and God. This dimension of theology and of the Church is of paramount importance and should be of greater significance in contemporary theological thought.

~Bishop Maxim Vasiljevic, excerpt from History, Truth, Holiness, available at Eighth Day Books