Heroism and the Spiritual Struggle

RUSSIA has experienced a revolution; but this revolution has not achieved what people expected from it. In many people’s minds, and, to a lesser extent, in our age as a whole, the entire legacy still remaining of the positive gains of this movement for liberation has a problematic character. Russian society, exhausted by these earlier exertions and failures, is now in a kind of torpor, a state of apathy, spiritual fragmentation, depression. The Russian state so far shows no sign of renewal of vigor which it so much needs; as if in a land of dreams, everything is once again frozen into immobility, bound in invincible slumber. Russian society, under the cloud of such a high number of death sentences, an unusually high crime rate, and a general coarsening of manners, has positively regressed. Russian literature is awash with the turbulence of unrestrained pornography and works of sensationalism. Hence the spread of depression and the fact that people have fallen into a state of profound misgiving as to the future of Russia in the longer term. And in any case, as a result of this experience, the rose-tinted utopia of the old-fashioned Westernizers is now already just as much of an impossibility as the naïve, rather precious spirituality and faith of the Slavophiles. The revolution has brought into question the very capacity for life of Russian society and the Russian state: if we do not reckon with this historical experience, the historical lessons of the revolution, it will be impossible for us to make any kind of affirmation about Russia, impossible simply to repeat what has been said in the past, whether by Slavophiles or by Westernizers.

In the wake of the political crisis, a spiritual crisis has also arisen which demands deep and concentrated reflection, approfondissement , self-examination and self-criticism. If Russian society is in fact still alive, still capable of living, if it contains hidden in itself the seeds of a future, then this capacity for life must be revealed above and before all else in a willingness and an ability to learn from history. For history is not only chronology, the recording of a succession of bare facts; it is a living experience of good and evil, constituting the condition for spiritual growth. Nothing is so perilous as the deadly immobility of mind and heart in an obstinate conservatism for which it suffices to repeat the past, or simply to keep at bay the lessons of life by means of the mysterious hope for a new “advance of consciousness,” elemental, fortuitous, unplanned.

Reflecting on our experience in the past few years, it is in fact impossible to see in all this a pattern only of historical contingency or a mere play of elemental forces. What has happened here is a pronouncing of historical judgment, a weighing in the balance of the various participants in the historical drama, an auditing of the account of an entire historical epoch. The “liberation movement” did not lead to the results it should have, and, it seems could have, let to; it brought neither reconciliation nor regeneration, nor did it lead to a strengthening of the Russian political system (although it did leave behind it one seed for the future in the form of the State Assembly, the Duma) or an improvement in the national economy. This was not only because it proved to be too weak for the struggle with the darker forces of history; it was also, to a still greater degree, unable to succeed because it proved itself inadequate to the scope of its task in virtue of the weakness produced by internal contradictions. The Russian revolution developed an immense destructive energy, like a huge earthquake, but its constructive powers turned out to be far weaker than the destructive. This bitter knowledge is stored away in the spirits of many, a shared sum of experience. But does it follow that this disillusion is never to find words, never to be plainly expressed, that the question can be posed of how all this comes to be so?

I have already observed that the revolution was an affair of the intelligentsia. Its spiritual direction was in the hands of our intelligentsia with their particular world-view, their conventions and tastes, their social mores. Members of the intelligentsia themselves, of course, do not admit this (this is what being a member of the intelligentsia means), and they will, each according to his own catechism, cast this or that social class in the character of sole motivator of the revolution. We do not deny that without the whole ensemble of historical factors (of which the most important was, of course, a disastrous war), and without the presence of the very serious and vital interests of different social classes and groups, these groups would not have been able to stir from their places and involve themselves in one general ferment; but all the same, we want to insist that the whole baggage of ideas, the whole spiritual arsenal, so to speak, along with the leading fighters and marksmen, agitators and propagandists, were provided for the revolution by the intelligentsia. Spiritually speaking, it was they who gave shape to the instinctive aspirations of the masses, kindled their enthusiasm and, in a word, became the nerves and the brain in the gigantic body of the revolution. In this sense, the revolution is the spiritual child of the intelligentsia; but if so, it follows that its history is the verdict of history upon the intelligentsia.

The spirit of the intelligentsia,

this creation of Peter the Great, is at the same time also a key to the future

destiny of Russian society and the Russian state. For good or ill, the destiny

of Petrine Russia is still in the hands of the intelligentsia, no matter how

they have been attacked and persecuted, no matter how weak, even powerless,

they have proved to be at this particular historical moment. They represent

Peter the Great’s “window thrown open on to Europe,” the window through which

the atmosphere of the West reached us, an atmosphere both vivifying and

poisonous. This handful of people have enjoyed a near-monopoly of European

culture and enlightenment in Russia; it is the prime means by which this

movement is advanced among Russia’s hundred million people; and if Russia is

not able to survive the threat of political and national death without such

enlightenment, which is so eminently and manifestly the historical vocation of

the intelligentsia, how terrifyingly weighty is its responsibility for our

country’s future, its immediate as much as its remoter future! That is why, for

the patriot, who loves his people and is deeply affected by the needs of the

Russian state, there is at present no more pressing issue for reflection than

the nature of the Russian intelligentsia, and, at the same time, no more

oppressive and disquieting anxiety than whether it can rise to the height of

its task: whether Russia will receive what the Russian spirit so urgently needs

from its cultivated class – enlightened reason and firmness of purpose – or

whether, on the contrary, the intelligentsia will join forces with the legacy

of the Tatar period, already so prevalent in our state and society, to destroy

Russia. Many in Russia after the revolution; and, as a result of their

experience of its, went through sharp disillusion with the intelligentsia and

became skeptical about its fitness for its historical role; in the specific

failures of the revolution they discerned the bankruptcy of the intelligentsia

itself. The revolution uncovered, underlined and reinforced those aspects of

its spiritual physiognomy that had earlier been foreseen in their full and true

significance only by a few people (Dostoevsky above all); it proved to be a

kind of spiritual mirror for the whole of Russia, and for the intelligentsia in

particular. To be silent about these features now would be not only

impermissible but positively criminal. All our hope must now rest upon this –

that these years of social decline may also prove to be years of saving

penitence in which spiritual energies can be resurrected and a new people

formed and educated, new toilers in the fields and pastures of Russia. Russia

is not capable of regeneration so long as its intelligentsia (along with many

others) has not been regenerated. The duty of conviction and patriotism is to

speak loud and clear on this matter.

The character of the Russian intelligentsia overall is built up under the influence of two basic factors, internal and external. The first was the unbroken and relentless weight of police pressure, capable of flattening out and annihilating a more weak-spirited group; that the intelligentsia preserved its life and energy under such pressure witnesses at all events to the quite exceptional character of its courage and vitality. The isolation from life at large, to which the atmosphere of the ancien r égime condemned the intelligentsia, reinforced the elements of an “underground” psychology which already characterized their spiritual profile. It also froze the inner life of the intelligentsia into immobility, sustaining and to a certain extent legitimizing its political obsessiveness (a Hannibal-like sworn dedication to the struggle against autocracy), as well as blocking off the possibility of a normal spiritual development. A more favorable external environment for such a development has only now come to exist; it is impossible not to see some spiritual gain resulting from the liberation movement in this respect at least. The second, internal factor determining the character of our intelligentsia is its distinctive world-view and – connected with this – its essential spiritual “style.” I cannot but see the most fundamental mark of the intelligentsia in its relation to religion. It is not possible to understand the basic character of the revolution without keeping this question of the intelligentsia’s relation to religion at the center of our attention. But Russia’s historical future too is bound up with the resolution of the question of how the intelligentsia is to define its stance in respect of religion: whether it remains content with its former deadness in this respect or whether a transformation in this area already awaits us, an authentic revolution in minds and hearts.

II

It has often been remarked

(following Dostoevsky) that the “spiritual profile” of the Russian

intelligentsia has some characteristics of a religious nature, occasionally

even approximating to Christian qualities. These features developed primarily

as a result of its external historical fate: on the one hand, government

persecution, creating a self-perception in terms of martyrdom and confession;

on the other, a forcible separation from life at large, developing a dreamy and

visionary tendency, sometimes a kind of refined preciousness or utopianism, a

generally deficient sense of reality. Connected with this is another feature of

the intelligentsia: its alienation from the petty bourgeois organization of

life in Western Europe – the values of its daily existence, its labor-intensive

economy, and also its pedestrian and constrained character – though this

alienation may not last for ever. In the works of Herzen we have a classic

expression of the conflict between the Russian intelligentsia and the European

bourgeoisie; but the innate tendencies of this mentality have more than once

been expressed in more recent Russian literature. The closed and fixed nature

of the bourgeois mind is sickening and cloying to the intelligentsia, though we

are all aware how much we have to learn, and how urgently, from Western man

about the technical side of life and labor. But the Western bourgeoisie in its

turn finds the footloose corps of Russian émigrés repugnant and incomprehensible –

nourished as they are by memories of Stenka Razin and Emilian Pugachev,

although these are reconceived in terms of contemporary revolutionary jargon;

and in recent years this antagonism of spirit seems to have reached an

unprecedented pitch. If we try to analyze this anti-bourgeois spirit in the

Russian intelligentsia, it appears to be a mixtum

compositum

, made up of very diverse elements. There is a trace here of the

inherited aristocratic consciousness – generations of freedom from anxiety

about one’s daily bread, freedom from the general workaday “bourgeois” level of

existence. There is a significant element of plain “unformedness,” lack of

experience of sustained and disciplined labor and of planning the organization

of one’s life. But there is also, undoubtedly, a perhaps less marked element of

unconsciously religious aversion to the bourgeois soul, “the kingdom of this

world” and its placid self-sufficiency.

A certain worldliness, the eschatological vision of the City of God, the coming kingdom of righteousness (under a variety of socialist pseudonyms), and so too a burning ardor for the salvation of humanity (from suffering, at least, if not from sin) – these make up the familiar, invariable and distinctive characteristics of the Russian intelligentsia. Pain in the face of the disharmony of life and the yearning for this pain to be overcome are especially characteristic of the major writers among the intelligentsia (Gleb Uspensky, V. Garshin). In this yearning for the City that is to come, in comparison with which earthly reality grows pale, the intelligentsia perhaps preserves, in very recognizable form, the features of the ecclesial life it has lost. How often in the Second Duma have I heard in the passionate speeches of the atheistic left – strange to say! – resonances of Orthodoxy psychology, suddenly revealing the influence of its spiritual formation and implantation.

In general these conventions of the spirit, nurtured by the Church, explain more than one of the best traits of the Russian intelligentsia, traits that are lost in proportion to its distance and defection from the Church – a certain puritanism, an ethical rigorism, a peculiar sort of asceticism, a general severity or sobriety in personal life. Such leaders of the intelligentsia as, for example, Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky (both of them ex-seminarians, both brought up in families of devout religious character) preserve almost intact their earlier moral character – which, however, is gradually lost by their historical progeny. These Christian features, assimilated piecemeal, unwittingly and involuntarily, through the medium of the general environment, family, nurses, a whole spiritual atmosphere nourished by the Church, shine through in the “spiritual physiognomy” of the best and greatest among those who were active in the revolution. However, in view of the idea that all real contrasts and oppositions in spiritual ethos between Christianity and the intelligentsia can just be blotted out thanks to all this, it is important to establish that these Christian features have only a residual, borrowed, and in a certain sense autistic character, and tend to disappear in the degree to which former Christian practice is attenuated as the typical character of the intelligentsia evolves and reveals itself more fully, manifesting itself most powerfully at the time of the revolution, when it casts off the last vestiges of Christianity.

The Russian intelligentsia, especially in earlier generations, also possessed a native sense of guilt in respect of the common people – though this “social repentance” was, of its nature, directed not towards God but towards “the people” or “the proletariat.” Although these feelings in the “penitent aristocrat” or the “ d éclass é intellectual” have, in their historical origins, a certain flavor of the aristocratic milieu, they do carry the imprint of a particular kind of depth and pathos in the character of the intelligentsia. And to this we must also add its capacity for sacrifice, the consistent readiness for sacrifice among its highest representatives – even a positive quest for the sacrificial. Whatever may be the psychology of this, it certainly reinforces the unworldly cast of mind in the intelligentsia, which makes its ethos so alien to the bourgeois mind and gives it still more the character of a particular sort of religious sensibility.

Nonetheless, despite all this, it is well known that no body of intellectuals is as consistently atheistic as the Russian. Atheism is the common creed into which those who are received into the bosom of the church of the humanist intelligentsia have to be baptized – not only those who have come from the cultivated classes, but those too who come from the population at large. The pattern is already fixed from the beginning in the life of Belinsky, the spiritual father of the Russian intelligentsia. And so, just as every social milieu develops its own mores, its particular beliefs, so the traditional atheism of our intelligentsia becomes itself a comprehensive and distinctive “style,” something not even talked about, as if this silence were a mark of good taste. In the eyes of our intelligentsia, guaranteed enlightenment and culture is synonymous with religious indifferentism and apostasy. There is no debate about this among the differing factions and parties or “tendencies”; on this point they are at one. It is the pervasive diet of all the debased and impoverished culture found among the intelligentsia, in its papers and journals, its projects and programs and mores and prejudices – like the blood, oxygenized by breathing, and diffusing itself through the whole organization. There is no more significant fact than this in the history of the Russian Enlightenment. And on top of this we should recognize that Russian atheism is by no means a form of conscious apostasy, the fruit of complex, painful and protracted labor of mind, heart and will, weighing heavily on the whole life of the personality. On the contrary, it is most frequently sustained by an act of faith and preserves all the marks of a naïve religious commitment – though they are all turned upside down. This is unaffected by the fact that it also takes on polemical, dogmatic and would-be scientific forms: such faith preserves at its base an uncritical and unexamined foundational axiom – that science is competent to provide a final solution to the questions of religion, and moreover can solve them only in a negative way. This goes along with a suspicious and uneasy relationship to philosophy – metaphysics in particular, which is rejected and condemned in advance.

This creed is shared equally among the instructed and the uninstructed, the old and the young. It is a philosophy absorbed in adolescence – whose onset is, of course, earlier for some and later for others; and in this phase the rejection of religion is something that is usually taken on lightly and almost naturally, with belief in science and in progress replacing it instantly. Our intelligentsia, once rooted in the soil, remain under the sway of this belief their whole life long, in the majority of cases, continuing to see these questions as adequately revolved and finally decided, hypnotized by the generally prevailing unanimity of opinion about this. Boys grow into mature men; and some of them acquire serious scientific knowledge and become noted specialists. In such a case, they will cast into the scales their authority as “men of science” in favor of the atheism they learned to profess as adolescents, the atheism that was dogmatically taken for granted in the schoolroom – although in fact, where these issues are concerned, they have no more authority than any reflective and sensitive person. This is how the spiritual atmosphere of our high schools is built up; this is where the embryo intelligentsia is formed. And it is startling how little impression is made upon our intelligentsia by men of profound cultivation, intellect and genius, when such people summon them to an approfondissement of their religious sense, to an awakening from their dogmatic slumbers; how little notice was taken of the religious thinkers and writers of the Slavophile movement, of Vladimir Soloviev, Bukharev, Sergei Trubetskoi and others; how deaf our intelligentsia has been to the religious message of Dostoevsky – or even Tolstoy, despite the show of devotion to his name.

It is the dogmatic character of Russian atheism that is its most striking feature, the religious superficiality and frivolity, so to speak, with which it is accepted. But until recently, the problems of religious belief, in all their immense and exceptional seriousness and burning intensity, were not at all noticed or understood by “cultivated” society in Russia; religion has only ben of interest to the extent that it has been tied up with politics, or in relation to the propagation of atheism. There is an astonishing philistinism about religious matters among our intelligentsia. I do not say this simply to accuse, since there are, perhaps, particular historical reasons for this state of affairs, but by way of diagnosing a condition of the spirit. As far as religion is concerned, our intelligentsia has still not advanced beyond the adolescent stage; it is still incapable of thinking seriously about religion and has not allowed itself any conscious religious self-definition. It has never lived through the experience of religious thought and so remains, strictly speaking, not “above” religion, as it likes to think of itself, but simply outside of it. The best evidence for all this is provided by the historical development of Russian atheism. It was taken over by us from the West (not for nothing was it the first article in the creed of the Russian “Westernizer”). We accept it as the last word of Western civilization, at first in the shape of the Voltairean and materialist philosophy of the French encyclopedists, then in the form of atheist versions of socialism (Belinsky), later still as the kind of materialism popular in the sixties, positivism and Feuerbachian humanism; then, in more modern times, economic materialism, and in recent years, critical philosophy. In the dense foliage of the tree of Western civilization, with its roots going deep into a history of its own, our attention has been caught by one branch only. We have not known and not wanted to know all the rest, in full confidence that we are grafting ourselves onto the authentic stock of European civilization. But this civilization not only has a variety of fruits and a multiplicity of branches, it also has roots nourishing the tree, and to a certain extent countering the effects of a good man poisonous fruits with their healthy sap. So even negative doctrines have at their origins, among the other powerful and antithetical spiritual currents in their milieu, a psychological and historical significance very different from that which they acquire when they appear in a cultural vacuum and claim to provide a structure for the essential basis of an enlightened and civilized life in Russia. Si duo idem dicunt, non est idem [If two people say the same thing, it is not the same]. No culture was ever yet built on such a foundation.

It is often forgotten these days that Western European culture has religious roots to a very high degree; a good half of it is constructed on a religious basis with its foundations deep in the Middle Ages and the Reformation. Whatever may have been our attitude in the past to Reformation dogmatics and Protestantism in general, there is no denying that the Reformation provoked an immense spiritual advance in the whole of the Western world, including even those parts that remained faithful to Catholicism but were compelled to find renewal through controversy with their foes. The new personality of European humanity was, in this sense, born in the Reformation era, and this origin has left its mark: political freedom, liberty of conscience, human and civic rights were all proclaimed by the Reformation (at least in England). The significance of Protestantism, especially the Reformed tradition, Calvinism and Puritanism, for economic development has become clear in recent studies; the outworking of individualism in this tradition offered a welcome and apt structure of thought for those taking a leading role in the growth of national economies. Also in connection with Protestantism, very importantly, there occurred the development of modern science and, more particularly, modern philosophy. And the whole of this development advanced in precise and steady historical succession and order, without great gulfs and avalanches. The cultural history of the Western European world presents itself as a single connected whole, in which both the medieval and the Reformation epochs live on and still have their indispensable place alongside the tendencies and movements of more recent times.

Already in the Reformation era, the spiritual channel which was to be decisive for the Russian intelligentsia had been marked out. Alongside the Reformation, there was a revival of some of the features of paganism in the humanist Renaissance, the resurrection of classical antiquity. In parallel with the religious individualism of the Reformation, a neo-pagan kind of individualism was also gaining strength, exalting natural and unregenerate humanity. In this perspective, humanity was good and beautiful in virtue of its own nature, and all would be accomplished. Here is the root of all sorts of different theories about the law of nature, as also of modern doctrines about progress and the unlimited power of reforms in the external life of humanity to resolve the human tragedy – the root, therefore, of the whole of modern humanism and socialism. The apparent closeness in external form of religious individualism and pagan individualism does not cancel out their profound internal difference; so it is that we see in recent history not only a parallel development but also a conflict between these two currents of thought. In the history of ideas, the motifs of humanistic individualism are signally reinforced in the epoch of the so-called Aufklärung, in the seventeenth, eighteenth and part of the nineteenth centuries. It is the Enlightenment that draws the most radical negative conclusions from the original premises of humanism: in the religious sphere it moves, by way of both rationalism and empiricism, towards positivism and materialism; in ethics, by way of “natural morality,” to utilitarianism and hedonism. Materialistic brands of socialism can also be considered as a late-autumnal fruit of the Enlightenment. The general tendency of thought, which is in part a result of the fragmentation of the Reformation heritage, and is itself one of the factors promoting fragmentation in the spiritual life of the West, has been especially influential in recent history. It is the inspiration of the great French revolution and of most of the revolutions of the nineteenth century; and, at another level, it has also provided a spiritual foundation for the European mercantile bourgeois mentality, whose dominance superseded the “heroic age” of the Enlightenment. However, it is important not to forget that, although the face of the earth in Europe is so largely disfigured by the wide diffusion of Enlightenment philosophy among the mass of the population and is still under the ice-cap of bourgeois culture, the Enlightenment never played and does not now play a wholly exclusive or even a dominant role in the history of culture. The tree of European culture is still nourished, even if imperceptibly, by the spiritual sap of its ancient religious roots coursing through its pores. These roots, this healthy historical conservatism, are what guarantees the durability of the tree itself; although, to the extent that the Enlightenment permeates the root and bole, it sets in motion the process of wasting and decline. It is impossible, therefore, to conceive of Western European civilization as irreligious in its historical foundations; despite the fact that it has increasingly become so in recent generations. Our own intelligentsia in their enthusiasm for all things Western have not got beyond a merely external appropriation of the modern political and social ideas of the West, by taking them on board in association with the most extreme and strident forms of Enlightenment philosophy. But in the Russian intelligentsia’s option for the West, there is no essential accord with Western civilization in its organic entirety. For the Russian intellectual, the role of the “dark age” of the medieval period, the entire Reformation epoch with its immense spiritual advances, the whole development of scientific and philosophical thought apart from its extreme Enlightenment forms, all these pale into insignificance in historical perspective. First came barbarism, then civilization shone forth – i.e. the Enlightenment, materialism, atheism, socialism: there you have the beautifully simple philosophy of history characteristic of the average Russian intellectual. And so, in the present conflicts over the formation of Russian culture, it is necessary to contend – among other things – for a far deeper and more historically aware “pro-Western” stance.

Why has it turned out that our intelligentsia has been so ready to adopt these particular dogmas of the Enlightenment? Many historical reasons might be adduced for this, but it is a familiar enough truth that this choice is also a free act on the part of the intelligentsia themselves, for which they are accordingly to be held accountable before nation and history.

In any event, it is especially thanks to this option on their part that the interconnections in Russia’s cultural and educational life have been shattered; and this rupture is the cause of the spiritual sickness afflicting our nation.

III

Having rejected Christianity and

its established forms of life, our intelligentsia takes for granted, along with

atheism – or more precisely, instead

of atheism – the dogmas of a religion of the human-as-divine, in one or other

of its variants, as elaborated by the Western Enlightenment. What seems to be

the basic dogma characteristic of all its different forms is the belief in the

natural perfection of the human and the illimitable nature of the progress

achieved by human powers – but human powers that are, at the same time,

conceived in mechanistic terms. Just as all evil is to be explained by

disorders external to human social life, so there can be no personal guilt or

responsibility; the entire task of social construction consists in the conquest

of these external disorders by – naturally enough – external reforms. Once

providence and any sort of primordial plan realizing itself in history have

been denied, humanity puts itself in the place of providence and sees itself as

its own savior. This self-evaluation does not seem to interfere with the manifestly

contradictory belief in a mechanistic account of the human, sometimes in terms

of a crudely materialistic understanding of historical process, which explains

it in terms of the activity of elemental forces (as with economic materialism);

yet the human person remains, for all this, the sole reasonable and conscious

agent, his or her own providence. Such was the typical frame of mind in the

West, where it appeared in an age of cultural flowering, profoundly aware of

human possibilities, and given added psychological coloring by the sense of

cultural self-satisfaction characteristic of the expansion of bourgeois

prosperity. From the point of view of any religious evaluation, this

self-deifying of the European mercantile bourgeoisie – common to socialism and

individualism alike – looks like a repellent case of self-satisfaction and

spiritual larceny, a temporary deadening of religious consciousness; but in

fact in the West this “humanity-as-divine,” once having been through its Sturm und Drang

, has long since become,

though no-one can say for how long, tame and placid – as has European

socialism. In any case, it has so far proved powerless to destroy the

laboriously constructed vault of European culture (although this is what it

would in fact involve if it persisted long enough) and the spiritual health of

the European people. Age-long tradition and the historical disciplines of labor

have already practically triumphed over the influence of self-deification. But

it is otherwise in Russia, in the face of the ruptures that have happened here,

breaking the connections between the periods of our history. The religion of

the human-as-divine, and its essential core, the idea of self-deification, have

been accepted in Russia not only with the ordinary fervor of youth, but also

with the adolescent’s ignorance of life and of his own capacity, and so have

assumed almost feverish forms. Thus inspired, our intelligentsia has developed

the sense of a vocation to play the role of providence for the nation at large.

It recognized itself as the solitary bearer of illumination and of European

culture in this country, where – as it seemed to them – everything hitherto had

been steeped in impenetrable darkness, everything was barbarous and foreign.

The intelligentsia acknowledged its spiritual guardianship over Russia, and set

out to determine its salvation, as understood and conceived by itself.

The intelligentsia thus came to stand in relation to Russian history and contemporary society in the position of an heroic challenging force engaged in heroic conflict, a position resting on the intelligentsia’s own self-valuation. Heroism is, I believe, the word that reveals the fundamental nature of the intelligentsia world-view and ideal; more particularly, a heroism of self-apotheosis. The entire “economy” of its spiritual power is based on this self-perception.

The isolated position of the intellectual in this country, his uprootedness from the native soil, his harsh and difficult historical milieu, his lack of serious knowledge and historical experience – all this has stimulated the psychology of such “heroism.” The intellectual, especially at certain particular times, has fallen into a state of heroic ecstasy which has a manifestly hysterical coloring. Russia must be saved, and the intelligentsia can and must be shown to be its savior, in general and even in specific, named and particular, instances; and without it there is no savior and no salvation. Nothing so firmly reinforces the psychology of heroism than external persecution, oppression, conflict with its environment, danger and even destruction. And, as we know, Russian history is not lacking in this respect; the Russian intelligentsia has evolved and matured in an atmosphere of uninterrupted martyrdom. It is impossible not to bow down in reverence before their consecrated suffering. But such a genuflection before these sufferings in their immense past and heavy present scale, before this involuntary “crucifixion,” does not oblige us to keep silence about what still remains true, what we cannot pass over in silence, even in the name of piety towards the intelligentsia’s martyrology.

So it is suffering and oppression above all that secure the canonization of the hero, both in his own eyes and in those of the people around him. And just as, in consequence of the most deplorable features of Russian life, such a fate so often overtakes the intellectual at a young age, so this self-perception develops very early on; and the rest of his life then simply exhibits a consistent movement in a direction already established. Anyone can, without any trouble, find plenty of examples in literature, and from their own observation of life, of how, on the one side, you have the crippling effects of a police state, depriving people of the responsibility of useful work, and how, on the other, this very fact aids in the elaboration of a certain “aristocratic” quality of spiritual life, and – so to speak – the sense of a “patented” and authorized heroic style in its sacrificial activity. It is a matter for bitter reflection how much the psychology of Russian intelligentsia “heroism” owes to the pressure of resisting the influence of the police state, and how great this influence was, not only for people’s external fate but upon their spirits and their world-view as well. In any event, the influences stemming from Western “Enlightenment,” the religion of the human-as-divine and self-apotheosis, found an unexpected but powerful ally in the prevailing conditions of life in Russia. If the youthful intellectual, a male or female student, say, has any remaining doubt as to whether he or she is ripe for an historical mission to save their native land, the fact that the Department of Internal Affairs takes this ripeness for granted removes all remaining traces of uncertainty. The transformation of Russian youth or of yesterday’s average citizen into the heroic mold, with the interior labor demanded for such a transformation, in fact requires an uncomplicated and usually brief process of appropriating certain dogmas of the religion of the human-as-divine and the quasi-scientific “program” of some party or other that corresponds to the change in personal self-perception; after which the stage trappings of heroism grow up of their own accord. In the furthest future, refinements of suffering, bitterness at the harshness of authority and at the burdensome loss and sacrifice required, simply bring to perfection the building-up of this type of personality. Whatever may then befall them, they will certainly no longer doubt their mission.

The heroic intellectual is thus not content with the role of a humble worker (even if he is in fact obliged to confine himself to this); his vision is of being the savior of humanity or, at least, of the Russian people. What is necessary for him (in his dreams, of course) is the heroic maximum, not a half-baked minimum. Maximalism is an inalienable part of that intelligentsia heroism which revealed itself with such astonishing clarity at the time of the revolution. This was not a feature of one party only; this maximalist impulse is the very soul of heroism, since the hero cannot be reconciled to small things. Even if he sees no present or even future possibility of realizing this maximum, it is this alone which occupies his thoughts. He makes a leap of historical imagination, and, with little interest in the path he has leapt over, directs his gaze solely on the luminous point that marks the very limit of the historical horizon. Such maximalism shows clear signs of sickness, self-hypnosis, at the level of ideas; it paralyzes thought and furthers fanaticism, it is deaf to the voice of life. This offers some sort of answer to the historical question of why, during the revolution, it was the most extreme tendencies that prevailed, tendencies which meant that the immediate tasks of the moment were all defined in a more and more “maximalist” way (to the point of seeking the establishment of a republican or anarchist society). In this way, these more extreme and clearly senseless tendencies became more powerful and influential, and, given the general leftward drift of our pusillanimous and passive society, which so easily submits to force majeure , they squeezed out all the more moderate trends (suffice it to recall the hatred expressed by the “left bloc” for the “Kadet” party).

Every hero has his own mode of saving the human race and must work this out for his social program. Usually this means taking on the program of one of the existing political parties or sects, which, indistinguishable in the totality (being mostly based on materialist socialism or even, more recently, anarchism), go their different ways in terms of methods. It would be wrong to think that these party political programs have any psychological correspondence with what they mostly pretend to be – parliamentary parties as found in Western Europe; this is something far greater. It is a religious creed , a self-authenticating method of saving humanity, an ideological monolith which can only be accepted or rejected. In the name of belief in whatever the program is that presents itself, the best element in the intelligentsia subjects itself to the sacrifice of life and welfare, freedom and happiness. Although these programs are usually presented as “scientific,” which increases their attractiveness, it is better to say nothing about the degree of their actual “scientific” status; indeed, the most fervent of their adherents, considering the degree of their maturity and education, may in any case turn out to be the worst possible judges in this matter.

All feel themselves to be heroes, equally elected to be saviors and agents of providence – but all are not equally at one as to the ways and means of achieving this salvation. And since in fact the same central chords of the soul are touched by all the discordant variety of programs, partisan dissensions become entirely non-negotiable. The intelligentsia, smitten with “Jacobinism,” struggling towards a “seizure of power,” a “dictatorship” in the name of the people’s salvation, inevitably breaks up and dissolves into mutually hostile factions; and this is more sharply felt the more “heroic” temperature rises. Impatience and mutual controversy are such familiar characteristics of our partisan intelligentsia that we need only mention them in passing. Something like self-poisoning is going on in the life and activity of the intelligentsia. It is of the very essence of heroism that it presupposes a passive object to be worked on – the “people” or “humanity” being saved – amongst whom the hero, individual or collective, is invariably and exclusively conceived as a solitary figure. Once there is more than one hero or heroic project on the scene, rivalry and division are inevitable, since it is impossible to establish more than one “dictatorship” at the same time. Heroism as a global attitude to the world is a principle making for separation, not unification; it produces rivals, not fellow-workers.

Our intelligentsia, almost uniformly involved in struggling for collectivism, for the possibility of conciliarity [ sobornost ] in the life of human beings, appeared in its general ethos as anticonciliar, anticollective, since it carries in itself the principle of “heroic” self-assertion. The hero is, in a certain degree, a superman, standing to his neighbors in the arrogant and hectoring posture of a savior. For all its struggles for democracy, the intelligentsia is only a particular manifestation of class pride, “aristocratism,” setting itself disdainfully over against the life of the “natives” or “locals.” Anyone who has lived in intelligentsia circles will be perfectly familiar with this disdain and self-conceit, this consciousness of one’s own infallibility and contempt for all who think otherwise, this abstract dogmatism in which all teaching is cast in such circles.

As a result of its maximalism, the intelligentsia remains remote from arguments alike of historical realism and of scientific knowledge. Socialism itself is for them not a cumulative concept meaning progressive socio-economic transformation and consisting in a sequence of specific and entirely concrete reforms; not an “historical movement,” but a trans-historical “ultimate goal” (in the terminology of the well-known Bernstein controversy), for which a great historical leap forward must be accomplished by an act of heroism on the part of the intelligentsia. Hence the lack of any sense of historical actuality and the absolute geometrical straight lines in which opinion and judgment operate – the famous “principled” character of the intelligentsia. It seems that there is no word so often on their lips as this; everything is judged on “principle,” i.e. in fact abstractly , with no acquaintance with the complexity of an actual situation, frequently shaking off the constraints and difficulties of undertaking the proper analysis of circumstances that is required. Anyone who has had dealings with the intelligentsia at work will be familiar with the cost of their “principled” unpracticality, which leads often enough to “straining at gnats and swallowing camels.”

This maximalism constitutes the greatest obstacle to raising the level of general culture, especially in those matters which it considers to be its specialty, questions of a social and political nature. Once it has inspired itself with the idea that the end and the means of the movement are already fixed, and fixed, moreover, “scientifically,” then of course it loses interest in studying the mediating connections that bring the goal nearer. Whether consciously or not, the intelligentsia lives in an atmosphere of expectation, the expectation of a social miracle, a global cataclysm; it lives in a “chiliastic” frame of mind.

Heroism struggles for the salvation of humankind by its own powers and, moreover, by external means; hence the exceptional value ascribed to the heroic deed, the maximal incarnation of the program of maximalism. It is necessary to move something, to achieve something beyond ordinary power, yielding up in this cause whatever is most costly and precious, even life itself: such is the basic imperative of heroism. Becoming a hero, becoming a savior of humanity is possible though heroic deeds, ultimately beyond the bounds of mundane daily duty. This dream that lives in the soul of the intelligentsia, though realized only in some individuals, grows to universal proportions as a criterion of judgment and discernment in life. The achieving of such a heroic deed is both extraordinarily burdensome, since it requires a struggle against the extremely powerful instincts of fear and attachment to life, and extraordinarily simple, since it demands an effort of will that lasts only for a relatively short period of time, though the results conceived and expected from it are so highly esteemed.

Sometimes the enthusiasm for leaving life behind that results from an inability to come to terms with it, the inability to bear the burden of living, merges indistinguishably into heroic self-abnegation, so that the question must, reluctantly, be allowed to arise: is this heroism or suicide? Indeed, the intelligentsia’s calendar can commemorate many such heroes, who have performed prodigious feats in terms of suffering and protracted efforts of will, yet, in spite of the differences arising from the capacities of different individuals, still have the same tone or ethos in this respect.

Obviously, this attitude to the world is far better suited to the stormier moments of history than to its more serene periods, which are so oppressively tedious for heroes. The greatest opportunity for heroic action is when irrational “heightening of awareness,” exaltation, intoxicated lust for combat create an atmosphere of heroic daring and adventurousness; all these things are the active element of heroism. Hence the enormous power of revolutionary romanticism among our intelligentsia, their celebrated “revolutionary spirit.” We must not overlook the fact that revolution is understood in a negative way; it has no independent content but is characterized purely and simply as the denial of what it destroys. Thus the “pathos,” the emotional tone, of revolution is hatred and destructiveness. But one of the major figures of the intelligentsia, Bakunin, had already formulated the notion that the spin of destruction was simultaneously the spirit of creation; and this belief is a central nerve in the psychology of heroism. It simplifies the job of historical construction; on such an understanding, what this requires above all is strength of muscle and nerve, temperament and mettle. And, looking at the record of the Russian revolution, more than one case of such simplified understanding comes to mind …..

The psychology of intelligentsia heroism is shaped above all by the social groups and external conditions amongst which its character is most clearly revealed in the full consistency of undeviating maximalism. In our society, it is the young student world that presents just this happy combination of circumstances. Thanks to its physiological and psychological immaturity, its lack of life experience and scientific knowledge, and its compensating fervor and self-confidence, thanks to its privileged social position – but a position not yet as isolated as the world of the Western bourgeois student – our educated youth has become the most finished paradigm of heroic maximalism. And if the essential embodiment of spiritual experience in Christianity is starchestvo [the nurturing work of an “elder,” a spiritual father], then for our intelligentsia this role naturally comes to be played by student youth. Spiritual “paedocracy ,” the government of children, is the greatest evil of our society, and at the same time a symptomatic manifestation of the heroic ideals of the intelligentsia, its fundamental trait set out in accentuated or exaggerated form. This abnormal relationship, in which the judgments and opinions of the student generation turn out to be normative guiding influences for their elders, turns the natural order of things upside down, and is equally destructive for both parties. Historically speaking, this spiritual hegemony is connected with the leading role actually played by students in their irruptions into Russian history; psychologically, it is to be explained by spiritual fashions among the intelligentsia which remain throughout life – in its most lively and vigorous representatives – identical with those of student youth as far as world-views are concerned. Hence the profoundly bad and widespread indifference with which some among us view the way in which our young people, devoid of knowledge and experience, are fired by the heroic ideals of the intelligentsia to involve themselves in social experiments that are serious and dangerous in their consequences, and which, of course, in their actual execution only strengthen the arm of reaction. There has been hardly any adequately self-critical reflection on, or any appraisal of, the fact that we have groups whose membership is extremely youthful and immature committed to the most “maximalist” actions and programs. Worse still, many take this to be entirely natural. In the days of the revolution, “student” became the name by which members of the intelligentsia were popularly known.

Every stage of life has its advantages, and youth, with its still latent capacities, usually has a good many of them. Anyone concerned for the future will be concerned about the younger generation. But to be spiritually dependent on them, to seek their favor and approbation, to wait on their opinions and take them as a standard of judgment, this is evidence of the spiritual weakness of a society. In any case, it is a distinctive sign of the whole age we live in and of the essential structure of intelligentsia heroism that the ideal of the Christian saint, the podvizhnik involved in the spiritual struggle, should have been ousted by the image of the revolutionary student.

As recent years, alas, have shown, maximalism means are linked with maximalist goals. In this lack of fastidiousness about means, the heroic attitude of “everything is permitted” (which Dostoevsky had prophetically predicted in Crime and Punishment and The Devils ), the nature of intelligentsia heroism in its commitment to the human-as-divine finds its supreme articulation. In this context we can clearly see the process of self-deification at work, the putting of oneself in the place of God or of providence – and that not only in terms of goals and plans but in the ways and means of realizing them as well. I set out to realize my own idea, and for the sake of it I free myself from all ordinary morality; I give myself rights not only over the property but over the life and death of others, if this is what is needed for realizing my idea. Within every maximalist is a little Napolean of socialism or anarchism. Amoralism or (to use an older term) nihilism is the necessary consequence of self-deification, and it is here that the danger of self-deification lies hidden, the danger of internal disintegration, the inevitable fall that lies ahead. And the bitter disillusion that so many experienced in the revolution, the indelible remembered images of rampant self-will, acquisitiveness, mass terror, all this was manifestly more than a contingent effect of revolutionary action; it was the outworking of those spiritual potentialities that are necessarily bound up in the psychology of self-deification.

In fact, the path of heroism is open only for a few chosen souls and, what is more, only in exceptional moments of history: in the intervals between those moments, life is just the ordinary daily round. Now the intelligentsia is not made up entirely of heroic characters. Without the actual reality of heroic living, or at least the possibility of its appearance, “heroism” becomes mere pretense, a seductive pose; a peculiar spirit of heroic bigotry develops, a permanent “principled” opposition, an exaggerated sense of being in the right and a weakened consciousness of obligation and personal responsibility overall. The ordinary citizen, in some respects, above and in some respects below the level of the milieu in which he lives, begins to speak of himself with arrogance as soon as he has donned the uniform of the intelligentsia. This evil is particularly noticeable in provincial life in our country. Self-deification in one’s own estimation is well fitted for producing a certain inflated pretentiousness. A man deprived of absolute norms and firm principles for personal and social behavior will replenish his store from the resources of self-will and self-definition. This is why nihilism is such a appalling scourge, a dreadful spiritual cancer eating away at our society. The heroic “everything is permitted” is imperceptibly replaced by a plain lack of principle in all things, as far as personal life and conduct are concerned, the issues that fill up the span of ordinary mundane existence. This is one of the main reasons for the fact that in our society, with such an abundance of heroes, there is such a dearth of conscientious and disciplined people equipped for serious work, and the same younger generation so committed to heroism, the generation to whom their elders look for their own self-definition, so easily and imperceptibly changes into “superfluous” people or Chekhovian and Gogolesque characters, ending up in wine and gambling, if not worse. The clear-eyed genius of Pushkin lifts the veil on a possible future for Lensky, who dies with such tragic untimeliness, and sees in it only an unrelievedly prosaic landscape. Make the mental experiment of doing the same thing in relation to some other young man, one who is now surrounded by the aureole of heroism, seeing him in later years simply in the role of an ordinary worker, when the affectation of heroism has disappeared, leaving in his soul only the vacuity of nihilism. Not for nothing did Nekrasov, the poetic voice of the intelligentsia, author of “A Knight for an Hour,” sense that an early death is the ultimate apotheosis of an intelligentsia heroism.

Do not

grieve so foolishly for him:

It is good

to die young!

Relentless

mediocrity had no chance

To cast its

shadow upon him.

This affectation of heroism, with all its superficiality and transitoriness, explains the extraordinarily irresolute character of the taste and style of the intelligentsia, their beliefs and attitudes, changing according to the whims of fashion. Many are astounded by the radical changes of mind which have occurred over the last four years – the transition from the heroic revolutionary mindset to the nihilistic and pornographic – and also at the present epidemic of suicide, which they mistakenly explain with reference only to political reation and the heavy pressures of Russian life.

But both this course of events and its attendant hysteria appear natural to the intelligentsia; it prompts no alteration in their essential nature, which only shows itself more fully as the revolutionary festival gives place to the common daily round. False heroism does not go unpunished. The spiritual condition of the intelligentsia cannot but give cause for serious alarm. Far greater unrest is provoked by the spiritual attrition of the younger generation, and especially the fate of the children of the intelligentsia. Inconstant, cut off from the organic structures of life, devoid of any abiding support, the intelligentsia, with its atheism, its blinkered rationalism and general lack of fixed direction and firm principle in daily life, hand on all these characteristics to their children as well, the only difference being that these latter are deprived even in their infancy of the healthy nourishment that their parents received from the folk environment.

In the milieu of intelligentsia life, the ideas of personal morality, personal self-development, the attainment of personality itself are extremely unpopular (and conversely, the word “social” has a peculiar, sacramental character). Although the intelligentsia’s attitude to the world presents itself as the ultimate self-affirmation of personality, the self-deification of personality, the intelligentsia mercilessly castigates this same ideal of personality in its theoretical pronouncements, almost always reducing it without remainder to the sum of environmental influences and the elemental forces of history (in conformity with the general doctrine of the Enlightenment). The intelligentsia does not want to allow that there is any living and creative energy bound up in personality, and remains deaf to everything that touches closely on this problem; deaf not only to Christian doctrine, but even to the teaching of Tolstoy (in which there can certainly be found a healthy element witnessing to the ideal of a personal process of deeper penetration into the life of the self), and to all philosophical doctrines that compel attention to this question.

Meanwhile, it is precisely this lack of an adequate doctrine of personality that constitutes the intelligentsia’s chief weakness. The distortion of personality, the falsity of the ideal held up for its development, is the root cause from which the weaknesses and defects of our intelligentsia arise, its historical bankruptcy. The intelligentsia must be set on the right path from within, not from without – a task it can only perform for itself, through free, spiritual growth and achievement [ podvig ], invisible but entirely real.

V

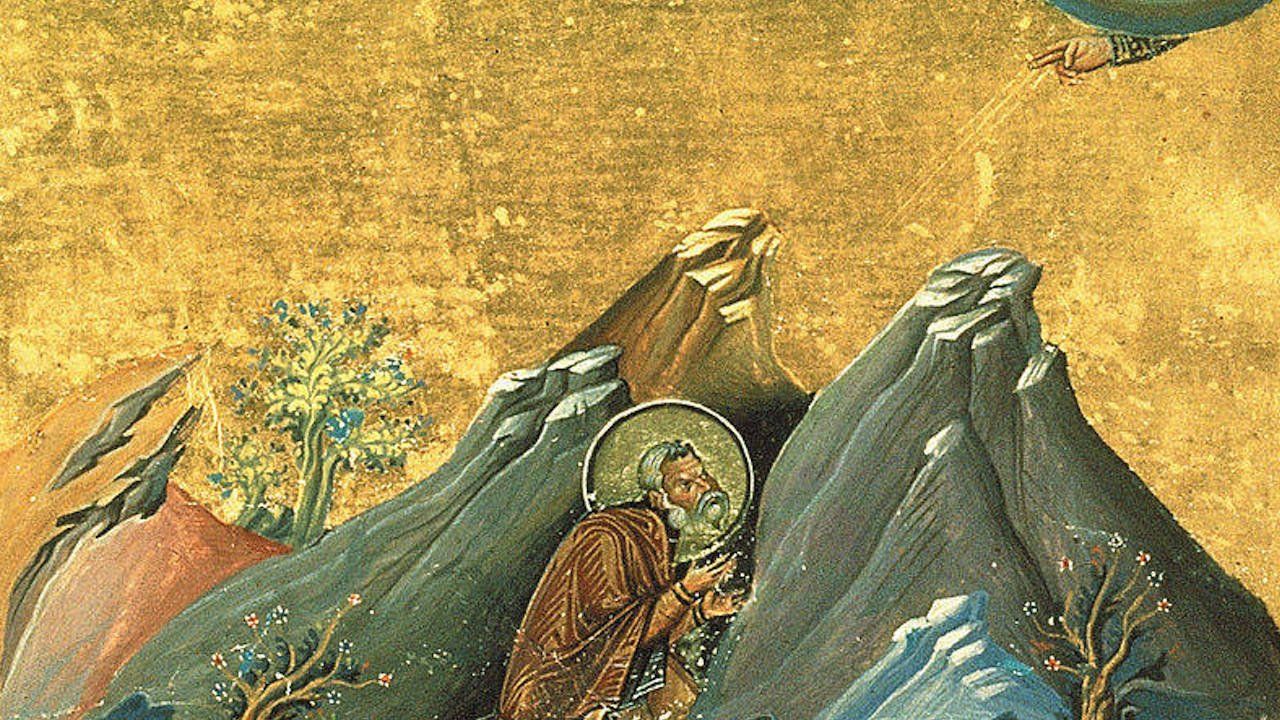

The peculiar

nature of intelligentsia heroism becomes clearer to us if we compare it with

its polar opposite in the spiritual realm – Christian heroism or, more

precisely, the Christian spiritual struggle [ podvizhnichestvo

]; for, in Christian terms, the hero is the “spiritual

athlete” [ podvizhnik

]. The

fundamental difference here is not so much external as internal and religious.

The hero, casting himself in the role of providence, arrogates to himself, in

virtue of this usurpation, not only a greater responsibility than can be borne,

but also a greater task than a human being can compass. The Christian podvizhnik

trusts in a divine

providence, without whose will not a hair falls from the head. In his eyes,

both history and the unique life of a human individual are realizations of this

divine purpose, although in particular details the divine economy of things is

beyond his grasp; here he must humble himself in the podvig

of faith. Thanks to this, he is liberated from heroic

posturing and pretension. His attention is concentrated on his immediate task,

his concrete obligations and the fulfilling of them with strict fidelity and

without delay. Naturally, both the determining and the fulfilling of these

obligations sometimes requires no less wide a horizon, no less breadth of

awareness, than the heroism of intelligentsia lays claim to. Here, however, the

concentration is on a consciousness of personal duty and its fulfillment, on

self-control; and this shifting of the center of attention onto the self and

its obligations, this liberation from a false image of oneself as the

(uninvited) savior of the world and the arrogance that invariably goes with it,

restores health to the soul, filling it with the sense of a wholesome Christian

humility. Dostoevsky, in his Pushkin lecture, called the Russian intelligentsia

to this spiritual self-renunciation, this sacrifice of the arrogant ego of the

intelligentsia in the name of a greater holiness: “Humble yourself, proud man,

and, above all else, break down your pride … Conquer yourself, quiet yourself –

and you will begin a great work, you will make others free, you will see good

days, for your life is fulfilled.”

In the milieu of the intelligentsia, no word is so unpopular as humility; there are few notions so prone to incomprehension and distortion, few notions on which it is so easy for intelligentsia demagogy to sharpen its teeth; and this, you could say, is the best evidence of all as to the spiritual nature of the intelligentsia. It lays bare its arrogance, the arrogance that rests upon the self-apotheosis of heroism. At the same time, humility, according to the unanimous witness of the Church, is the primary and fundamental virtue; but even outside the Christian sphere it is a quality that has its own full integrity, testifying, wherever it is seen, to a high level of spiritual development. It should be easy even for a member of the intelligentsia to understand that for scholars and savants, for example, the deeper and wider their knowledge, the greater their sense of being merely at the brink of the abyss of their ignorance; that success in knowledge is, for such people, accompanied by a growing understanding of their ignorance, an increase of intellectual humility. This is confirmed by the biographies of the greatest scholars. Conversely, confident self-sufficiency, the expectation of reaching a fully satisfactory level of knowledge by one’s own unaided powers, is a sure and certain symptom of scientific immaturity, or simply youthfulness.

The same sense of profound dissatisfaction with one’s own achievements and their failure to produce something conformable to one’s ideal of beauty – which is the task of art – is no less characteristic of our artists, for whom their work inevitably becomes a torment, even though it is only in this work that they discover their true life. You will find no true artist who is without this sense of abiding dissatisfaction with his creation – which could be called a kind of humility before beauty. And the same sensation of the limited character of individual powers and resources in the face of ever-expanding tasks holds of the philosophical thinker, the civic activist, the planner of social policy, and many more.

But if the natural and necessary character of humility can be relatively easily understood in these specific areas of human activity, why does it appear so difficult where the central sphere of spiritual life, moral and religious self-awareness and self-examination, is concerned? This is where the decisive significance of one or another higher-level criterion or ideal of personal life becomes plain: will this criterion of self-examination be the image of perfect divine personality, incarnate in Christ, or the self-deifying human agent in one or another of its limited earthly shapes (humanity, the people, the proletariat, the superman) – i.e., in the long run, the self-sufficient ego, which sets before itself only itself in a heroic posture. The podvizhnik looks at the limited and distorted world of human sin and suffering, especially as it exists in his own self, with the purified eyes of the spirit, and in so doing brings to light new imperfections; the sense of distance from the ideal is intensified. In other words, the ethical development of personality is accompanied by an increasing awareness of one’s imperfection, or (which comes to the same thing) is expressed in humility before God and “walking in the sight of God” (as this is expounded in the consistent testimony of ecclesial and patristic literature). And this distinction between heroic and Christian self-valuation penetrates the furthest corners of the soul, its whole sense of itself.

As a result of the absence of an ideal of personality (or, more precisely, the distortion of this ideal), all that relates to the religious “culture” of personality, its development and discipline, inevitably continues to be completely neglected among the intelligentsia. There is a lack of any of the absolute norms and values which are necessary for such cultivation, and which religion alone can provide. Above all, there is no understanding or awareness of sin – so much so that the very word has almost as barbarous an alien a sound in the ears of the intelligentsia as “humility.” All the power of sin, its tormenting weight, the ubiquity and profundity of its influence on the whole of human life, in a word, the entire tragedy of the human condition, from which, in God’s eternal plan, only Golgotha can provide deliverance, all this remains wholly outside the consciousness of the intelligentsia, who are still, as it were, in religious infancy – not above sin, but below the level at which they might be aware of it. Along with Rousseau and the Enlightenment, they have put their trust in the essential goodness of the natural man believing that the doctrine of original sin and the radical corruption of human nature is a superstitious myth that has no correspondence with moral experience. Thus there is overall no particular concern about the cultivation of personality (the much-despised business of “self-improvement”), nor any sense that there should be; all one’s energies should be entirely expended on the struggle to improve the environment. While they declare personality to be the product of the environment, they offer this very same thing, personality, as the agent for improving the environment, like Baron Munchausen pulling himself out of the quagmire by his own hair.

Many features in the structure of the intelligentsia’s life and soul and, alas, many of the sadder aspects and events of our revolution can be explained by this repudiation of the sense of sin, and a certain nervousness, to say the least, in mentioning it – features also of the spiritual decay that followed in the wake of the revolution. The intelligentsia has been feeding itself with many piquant dishes from the table of Western civilization, finally surfeiting and disordering a stomach that was damaged to start with; is it not time to recall the plain and coarse but entirely healthy and nutritious diet of the old Mosaic Decalogue, or to move on from there to the New Testament? …..

Heroic maximalism is wholly projected outwards, wholly directed towards the attainment of external goals; as regards personal life, over and above the heroic act and all that goes with it, this maximalism turns out to be minimalism – i.e. it simply leaves the personal dimension out of its purview. Hence too its incompetence in forming and perfecting a stable, disciplined personality, capable of real work, standing on its own feet, not on the crest of a wave of public hysteria which will in due course sink down again. Every representative of the intelligentsia is defined by this combination of maximalism and minimalism, in which maximal claims can be advanced with the most minimal foundation in personality. This is equally true in the sphere of scientific knowledge as in experience of life and self-discipline; and this is thrown into high relief in the unnatural hegemony enjoyed by student youth, in our “spiritual paedocracy.”

The world is understood very differently in the Christian spiritual struggle. In complete contrast to the arrogance of intelligentsia heroism, the struggle is above all a matter of maximalism in personal relations, in the demands made on oneself; and conversely, the harshness of external maximalism is here significantly softened. The Christian “hero,” the podvizhnik (in our admittedly rather provisional terminology), does not set himself to do the job of providence, and so does not link the destiny of history or humanity to his or anyone else’s individual efforts). In his activity, he looks above all to the fulfillment of his duty before God, to the keeping of God’s commandments; he is constantly turned Godward. He is obliged to fulfill this duty before God with the greatest possible completeness, and equally obliged to show both the greatest possible energy and the greatest degree of selflessness in discerning what constitutes this duty and its active performance. In a certain sense he too is bound to maximalism in action, but it is a wholly different sense. One of the most common misunderstandings where humility is concerned (one, moreover, that is not always bona fide ) is that Christian humility, the interior and visible conflict with self, self-will, self-deification, is always to be interpreted in terms of passivity at the exterior level, as a reconciliation with evil, as inertia and even servility, or at least inactivity in the external sense; and in all this, the Christian spiritual struggle is confused with what is only one of its many forms (though a highly important one) – monasticism. But the struggle, understood as internal establishing of personal reality, is compatible with all kinds of external activity, in so far as they do not contradict its basic principle.

Christian humility is particularly ardent in its opposition to the “revolutionary” frame of mind. Without going into this question in detail, I want only to point out that revolution – i.e. revolution as a particular program of political action – is not able of itself to settle the question of the spirit and ideals that should inspire it. When Dmitri Donskoi set out with the blessing of St Sergius to fight the Tartars, this was a revolutionary action in the political sense, a revolt against legally constituted authority; but at the same time it was, I believe, an act of Christian spiritual achievement in the souls of those involved, inseparably united to the active virtue of humility. And, conversely, the recent revolution, in so far as it was based on atheism, was remote in spirit not only from Christian humility but from Christianity in general. In the same way, there is an enormous spiritual difference between the Puritan revolution in England and the atheist revolution in France, as there is between Cromwell and Marat of Robespierre, between Ryleev or, more generally, the Christians among the Decembrists and more recent revolutionary activists.

In fact, of course, there may, in appropriate historical circumstances, be particular actions that can be called heroic, yet are wholly compatible with the psychology of Christian spiritual struggle; they are done not in the agent’s own name, but in God’s, not in an heroic spirit but in the spirit of interior labor and struggle, so that although they are “heroic” in outward form their religious psychology is wholly distanced from what that word suggests. “The Kingdom of Heaven suffers violence, and men of violence enter it by force” (Mt. 11:2): “violence” is required from all, the maximal effort of our energy is called out for the actualizing of the good. But such violent exertion does not give us the right to the pretensions of the heroic self-image, the right of spiritual arrogance, since it is no more than the fulfilling of a duty: “When you have done all that is commanded you, say, We are unprofitable servants; we have done no more than our duty” (Lk. 17:10).

The Christian struggle is a matter of unremitting self-control, war with the lower and sinful levels of one’s ego, ascesis of spirit. If heroism is characterized by the brief flare of intensity and the aspiration to do great deeds, here, in contrast, the norm that appears is far more of an even flow, “moderation,” a sustained habit of life, unwavering self-discipline, endurance and perseverance – precisely the qualities lacking in the intelligentsia. Faithful performance of one’s duty, bearing of one’s own cross, repudiation of self (not only in external things, but even more in the interior sense) and leaving the rest to providence – these are the marks of authentic spiritual labor. In monastic practice, there is a very fine expression for this religious and practical idea – “obedience” [ poslushanie ]. This is the term applied to any and every particular job assigned to a monk, applied equally to all tasks, whether study or heavy physical labor, so long as they are done as a matter of religious duty. The notion can be extended beyond the boundaries of the monastic life and applied to all work of whatever kind it may be. The physician and the engineer, the professor and the political activist, the manufacturer and his workers can all of them in the fulfilling of their duties find themselves guided not by their own personal interest, spiritual or material, but by conscience and the imperative of duty in carrying out their “obediences.” This discipline of obedience, this “secular” asceticism ( innerweltliche Askese , as the Germans say), has had immense influence over the development of personality in diverse sorts of work in Western Europe – a development still perceptible in our own day.

The reverse side of the maximalism of the intelligentsia appears in their historical restlessness, their lack of historical patience or temperance, the striving to bring about a social miracle – the practical negation of their theoretical commitment to evolutionism. In contrast, the discipline of “obedience” should assist the development of patience in the face of history, self-mastery, stability of life; it teaches us how to endure the burdens of history, the yoke of obedience in history; it creates a certain “earthiness,” a sense of connectedness with the past and grateful indebtedness to it – something which is now so easily forgotten for the sake of the future. It restores the moral bond between children and parents.

Pure humanistic progress, in contrast, means contempt for one’s forebears, a turning away from one’s past and a wholesale condemnation of it, an ingratitude that is both historical and frequently, simply personal, a legal act of spiritual separation between fathers and children. The hero creates history according to his plan, he – so to speak – initiates history out of the resources of his own selfhood, and considers the realities of the world as raw material, passive objects for his influence to work on. The rupture of historical continuity in sensibility and will makes this inevitable.

The foregoing parallel allows us to draw a general conclusion about the relation between intelligentsia heroism and the Christian spiritual struggle. Beneath a certain external similarity there is no inner relationship at all between them, not even an underlying contingent one. The task of heroism is the external salvation of humankind (or more exactly, the future members of humankind) by its own powers and planning, “in its own name”; the hero is the person who, in the highest degree, brings his idea to realization, even if he loses his life for its sake. He is a “man-God.” The task of the Christian struggle is to transform one’s own life by the imperceptible process of self-renunciation, obedience; to perform one’s work with whole-hearted endeavor, self-discipline, self-mastery, but also to see both it and oneself as an instrument of providence. The Christian saint is the person who, in the highest degree, reorders his personal will and the whole of his empirical personality as far as possible, through an uninterrupted and unremitting ascetic effort [ podvig ], so as to let it be wholly permeated by the will of God. The image of this total “permeation” is the figure of the “God-man,” the one who comes “not to do his own will, but the will of his Father,” “he who comes in the name of the Lord.”

The distinction between Christian heroism (at least in theory) and intelligentsia heroism, which, historically speaking, has borrowed certain of its basic dogmas from Christianity (especially the ideas of the identical status of all people, the absolute worth of human personality, equality and fraternity) is liable to be generally minimized these days rather than exaggerated. This tendency is above all by the intelligentsia’s incomprehension of how great a gulf actually lies between atheism and Christianity, an incomprehension that has more than once led to the image of Christ being “improved,” with typical self-assurance, set free from its “ecclesiastical distortion” so as to bring into clearer outline its social democratic or revolutionary socialist character. We already have an instance of this in Belinsky, the father of the Russian intelligentsia. This has happened more than once – a process that is not only in poor taste but intolerable for religious sensibilities. But in other respects the intelligentsia has taken no interest in this rapprochement as such, resorting to it primarily in relation to political goals for the sake of facilitating “agitation.”

There is another far more subtle and seductive, though no less blasphemous, falsehood, that ahs come to be repeated in various forms particularly often in recent years: this is the assertion that the maximalism of the intelligentsia and its revolutionary spirit – shown, in my view, to be spiritually grounded upon atheism – is distinguished in essence from Christianity only by its lack of explicit religious confession. Substitute the name of Marx or of Mikhailovsky for that of Christ, Capital for the Gospel or, better, the Apocalypse (for ease of citation), or, indeed, change nothing at all, and it remains only to reinforce the revolutionary spirit of the intelligentsia, to carry forward the revolutionary action of the intelligentsia, for a “new religious consciousness” to come to birth out of all this (as if there were not already a sufficient example of what this carrying through of an intelligentsia revolution involves, as an example that brings to light all its spiritual potential, in the shape of the great French Revolution). If in the days before the revolution it was relatively easy to confuse the suffering and persecuted member of the intelligentsia, bearing on his shoulders the burden of the heroic battle against bureaucratic absolutism, with the Christian martyr, this has become far more problematic in the wake of the spiritual self-disclosure of the intelligentsia during the actual period of the revolution.