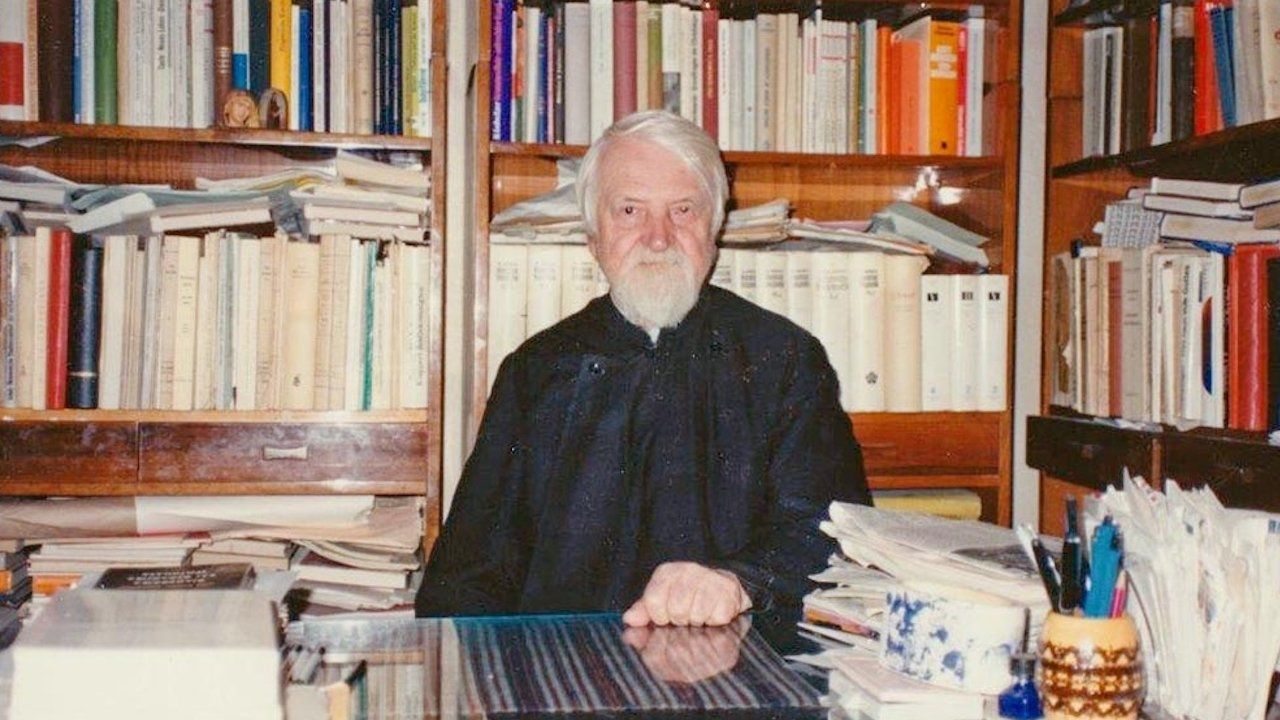

Fr Dumitru Staniloae on the Filioque

by Fr. Joshua Burnett

Feast of St Pachomius the Great, Founder of Coenobitic Monasticism

Anno Domini 2021, May 15

Fr. Dumitru Staniloae’s 1981 essay for the World Council of Churches is just as dense and tangled as its title: “The Procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and His Relation to the Son, as the Basis of Our Deification and Adoption.” Nevertheless, it rewards the relentless bushwhacker. The essay is one of a handful of WCC papers collected into the book Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: Ecumenical Reflections on the Filioque Controversy. Ostensibly, Staniloae is responding to the papers of a Catholic (Fr. Jean-Miguel Garrigues) and a Protestant (Jürgen Moltmann). But in reality, the figure that provokes the most substantial response from Staniloae is Karl Barth. Although Barth is never named in the essay, Staniloae cannot avoid addressing the substance of Barth’s critique of those who would do away with the filioque. (That critique can be found in the final section of Church Dogmatics I/1.)

Barth is not the first to criticize those of us who refuse to add the phrase “and the Son” to the Nicaean Creed’s declaration that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father. Indeed, at various times Eastern Christians themselves have recognized that dismissing the filioque invites legitimate questions regarding the eternal relationship between the Spirit and the Son. The relation between the Son and the Father is clear (the Father begets the Son), and the relation between the Spirit and the Father is clear (the Spirit proceeds from the Father), but what is the relation between the Spirit and the Son? The most conclusive answer to this question in the East was composed by Patriarch Gregory of Cyprus in the 13th century, and Staniloae resuscitates his argument for our benefit. (Short answer: The Spirit both “reposes” in the Son and “shines out” from Him.)

But Barth’s critique is not directed at the supposed failure of the East to articulate the eternal relation between the Son and the Spirit. Barth has a different, perhaps more pertinent concern. He is concerned to maintain a relationship between theological dogma and lived reality. The God of revelation must be identical with God as He is in Himself. If there is an unbridgeable ditch between temporal truths and the eternal truths of God, then God’s revelation of Himself has no integrity. Barth believes that such a ditch exists for those who reject the filioque. I was hardly surprised to see Staniloae tossing that accusation right back: the ditch between speculative theology and practical life exists not for those who reject the filioque but for those who affirm the filioque. Take that!

But, such a riposte belies a deeper agreement between Barth and Staniloae. Both are concerned to relate our formulations of God-in-Himself to our understanding of God’s being in our midst. Here is how Staniloae puts it:

In the East the Trinitarian relations are seen as the basis for the relation of the Trinity to creation and for the salvation of creation. (p. 178)

For Staniloae, the fact that we are brought into the life of the Son has consequences for how we conceive of the eternal relationship between the Son and the Spirit.

We are raised up in the Son, who is the eternal, filial dwelling place of the Spirit and with the Son we too become eternal, filial habitations for the Spirit. This is why the eternal relation of the Son to the Spirit is the basis of the sending of the Spirit to us by the Son. (p. 182)

Theology is not pure speculation. It is born of reflection on the economy of God. That is to say, our understanding of who God is in Himself and our understanding of how God acts toward His creation are interrelated. One informs the other, and vice versa.

Jesus Christ, by His incarnation, death, and resurrection, has crossed the divide between uncreated and created and has made a way for mankind to ascend, through death, to the right hand of the Father. By our death—death to self and, eventually, death of our physical body—we are united with Christ. Thus, Christ’s eternal relationship with each of the other persons of the Trinity provides a parallel for our relationship with those persons. Since Christ is the Son of the Father, when we are united with Christ we too are made sons of the Father, by adoption. This aspect—being made sons of the Father—has been well-articulated in theologies East and West.

What has not been so well-articulated is how our relationship with the Spirit parallels Christ’s relationship with the Spirit. And this is precisely what Staniloae seeks to remedy in his essay (though his articulation could be a bit more… articulate). Since the Son is the place of repose of the Spirit and since the Spirit “shines out” from the Son, then when we are united with Christ we become—by grace—places of repose of the Spirit and the Spirit “shines out” from us. This has been the Eastern view at least since the 13th century.

But some filioque-philes in the West hold the view that the Spirit proceeds from the Son as from a point of origin. If Christ, in His eternal relationship with the Spirit is an originator of the Spirit, then when we are united with Christ we too would have to become—by grace—a point of origin of the Spirit. But what would that mean, for the Holy Spirit to proceed from us by grace? Any attempt to conceive of it approaches blasphemy. We cannot be originators of God! Instead, it is more proper to say that the Holy Spirit—by grace—reposes in us and shines out from us, as he does from the Son. If the filioque is used at all, we must be careful to see Christ not as an originator of the Holy Spirit but as a conduit for the Holy Spirit.

God intends that we fully participate in the life of Christ. Thus, the life of Christ must be something in which we can participate. For Staniloae, it is not just God’s revelation of Himself but also His divine action of bringing us up into Himself that informs our conception of God-in-Trinity.

*Fr Joshua Burnett is the Priest at Holy Cross Orthodox Church in Linthicum Heights, MD. He and his wife Kh. Meredith have nine children.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.