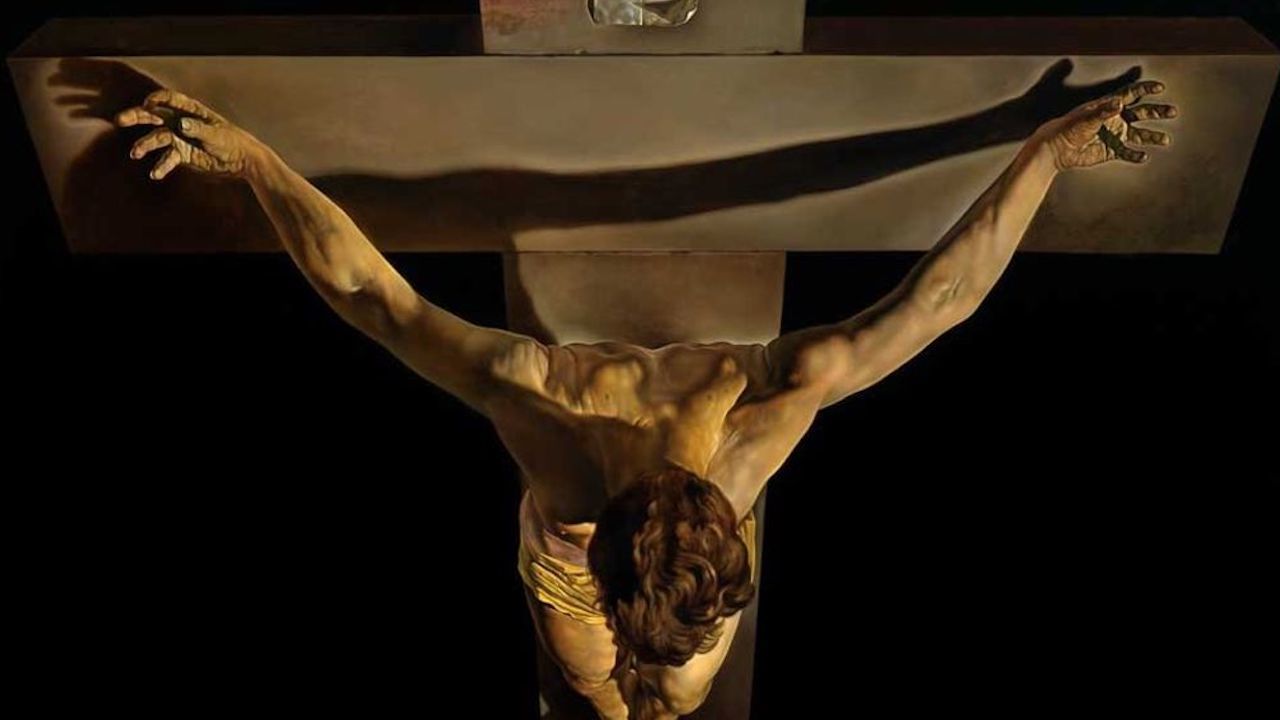

Christ of St. John of the Cross by Salvador Dali (A.D. 1951)

Well might the Roman Church have termed itself “catholic”: “universal.” There was barely a rhythm of life that it did not define. From dawn to dusk, from midsummer to the depths of winter, from the hour of their birth to the very last drawing of their breath, the men and women of medieval Europe absorbed its assumptions into their bones. Even when, in the century before Caravaggio, Catholic Christendom began to fragment, and new forms of Christianity to emerge, the conviction of Europeans that their faith was universal remained deep-rooted. It inspired them in their exploration of continents undreamed of by their forefathers; in their conquest of those that they were able to seize, and reconsecrate as a Promised Land; in their attempt to convert the inhabitants of those that they were not. Whether in Korea or in Tierra del Fuego, in Alaska or in New Zealand, the cross on which Jesus had been tortured to death came to serve as the mot globally recognized symbol of a god that there has ever been. “Thou hast rebuked the nations, thou hast destroyed the wicked; thou hast blotted out their name for ever and ever” (Ps. 9:5). The man who greeted the news of the Japanese surrender in 1945 by quoting scripture and offering up praise to Christ was not Truman, nor Churchill, nor de Gaulle, but the Chinese leader, Chiang Kaishek. Even in the twenty-first century, as the tide of Western dominance palpably retreats, assumptions bred of Europe’s ancestral faith continue to structure the way that the world organizes itself. Whether in North Korea or in the command structures of jihadi terrorist cells, there are few so ideologically opposed to the West that they are not sometimes obliged to employ the international dating system. Whenever they do so, they are subliminally reminded of the claims made by Christianity about the birth of Jesus. Time itself has been Christianized.

How was it that a cult inspired by the execution of an obscure criminal in a long-vanished empire came to exercise such a transformative and enduring influence on the world? To attempt an answer to this question, as I do in this book, is not to write a history of Christianity. Rather than provide a panoramic survey of its evolution, I have sought instead to trace the currents of Christian influence that have spread most widely, and been most enduring into the present day. That is why – although I have written extensively about the Eastern and Orthodox Churches elsewhere, and find them themes of immense wonder and fascination – I have chosen not to trace their development beyond antiquity. My ambition is hubristic enough as it is: to explore how we in the West came to be what we are, and to think the way that we do. The moral and imaginative upheaval that saw Jesus enshrined as a god by the same imperial order that had tortured him to death did not bring to an end the capacity of Christianity for inspiring profound transformations in societies. Quite the opposite. Already, by the time that Anselm died in 1109, Latin Christendom had been set upon a course so distinctive that what today we term “the West” is less its heir than its continuation. Certainly, to dream of a world transformed by a reformation, or an enlightenment, or a revolution is nothing exclusively modern. Rather, it is to dream as medieval visionaries dreamed: to dream in the manner of a Christian.

Today, at a time of seismic geopolitical realignment, when our values are proving to be not nearly as universal as some of us had assumed them to be, the need to recognize just how culturally contingent they are is more pressing than ever. To live in a Western country is to live in a society still utterly saturated by Christian concepts and assumptions. This is no less true for Jews or Muslims than it is for Catholics or Protestants. Two thousand years on from the birth of Christ, it does not require a belief that He rose from the dead to be stamped by the formidable – indeed the inescapable – influence of Christianity. Whether it be the conviction that the workings of conscience are the surest determinants of good law, or that Church and state exist as distinct entities, or that polygamy is unacceptable, its trace elements are to be found everywhere in the West. Even to write about it in a Western language is to use words shot through with Christian connotations. “Religion,” “secular,” “atheist”: none of these are neutral. All, though they derive from the classical past, come freighted with the legacy of Christendom. Fail to appreciate this, and the risk is always of anachronism. The West, increasingly empty tough the pews may be, remains firmly moored to its Christian past.

There are those who will rejoice at this proposition; and there are those who will be appalled by it. Christianity may be the most enduring and influential legacy of the ancient world, and its emergence the single most transformative development in Western history, but it is also the most challenging for a historian to write about. In the West, and particularly in the United States, it remains easily the dominant faith. Worldwide, over two billion people – almost a third of the planet’s population – subscribe to it. Unlike Osiris, or Zeus, or Odin, the Christian God still goes strong. The tradition of interpreting the past as the tracing of patterns upon time by his forefinger – a tradition that reaches back to the very beginnings of the faith – is far from dead. The crucifixion of Jesus, to all those many millions who worship him as the Son of the Lord God, the Creator of heaven and earth, was not merely an event in history, but the very pivot around which the cosmos turns. Historians, however, no matter how alert they may be to the potency of this understanding, and to the way in which it has swayed the course of the world’s affairs, are not in the business of debating whether it is actually true. Instead, they study Christianity for what it can reveal, not about God, but about the affairs of humanity. No less than any other aspect of culture and society, beliefs are presumed to be of mortal origin and shaped by the passage of time. To look to the supernatural for explanations of what happened in the past is to engage in apologetics: a perfectly reputable pursuit, but not history as today, in the modern West, it has come to be understood.

Yet if historians of Christianity must negotiate faith, so also must they negotiate doubt. It is not only believers whose interpretation of Christian history is liable to be something deeply personal to them. The same can be equally true of skeptics. In 1860, in one of the first public discussions of Charles Darwin’s recently published On the Origin of Species, the Bishop of Oxford notoriously mocked the theory that human beings might be the product of evolution. Now, though, the boot is on the other foot. “It is the case that since we are all 21st century people, we all subscribe to a pretty widespread consensus of what’s right and what’s wrong.” So Richard Dawkins, the world’s most evangelistic atheist, has declared. To argue that, in the West, the “pretty widespread consensus of what’s right and what’s wrong” derives principally from Christian teachings and presumptions can risk seeming, in societies of many faiths and none, almost offensive. Even in America, where Christianity remains far more vibrant a force than it does in Europe, growing numbers have come to view the West’s ancestral faith as something outmoded: a relic of earlier, more superstitious times. Just as the Bishop of Oxford refused to consider that he might be descended from an ape, so now are many in the West reluctant to contemplate that their values, and even their very lack of belief, might be traceable to Christian origins.

[...]

For a millennium and more, the civilization into which I had been born was Christendom. Assumptions that I had grown up with – about how a society should properly be organized, and the principles that it should uphold – were not bred of classical antiquity, still less of “human nature,” but very distinctively of the civilization’s Christian past. So profound has been the impact of Christianity on the development of Western civilization that it has come to be hidden from view. It is the incomplete revolutions which are remembered; the fate of those which triumph is to be taken for granted.

The ambition of Dominion

is to trace the course of what one Christian, writing in the third century AD, termed “the flood-tide of Christ” (Acts of Thomas 31): how the belief that the Son of the one God of the Jews had been tortured to death on a cross came to be so enduringly and widely held that today most of us in the West are dulled to just how scandalous it originally was. This book explores what it was that made Christianity so subversive and disruptive; how completely it came to saturate the mindset of Latin Christendom; and why, in a West that is often doubtful of religion’s claims, so many of its instincts remain – for good and ill – thoroughly Christian.

It is – to coin a phrase – the greatest story ever told.

Excerpted from Preface to Dominion, pp. 11-17. Book available at Eighth Day Books.

Members (Patrons+) receive 10% discount, plus many other perks!

Exercise the virtue of patience, resist Amazon, and support Eighth Day Books. Give them a call at 1.800.841.2541 between 10 am and 8 pm CST Mon-Sat and engage in a conversation about books and ideas with a live human person who reads books and loves to discuss them. Or, if you insist, visit their website at www.eighthdaybooks.com.