David Jones: History & Sacrament As Home

by Fr Gabriel Rochelle

Feast of St Tabitha the Widow, Raised from the Dead by the Apostle Peter

Anno Domini 2020, October 25

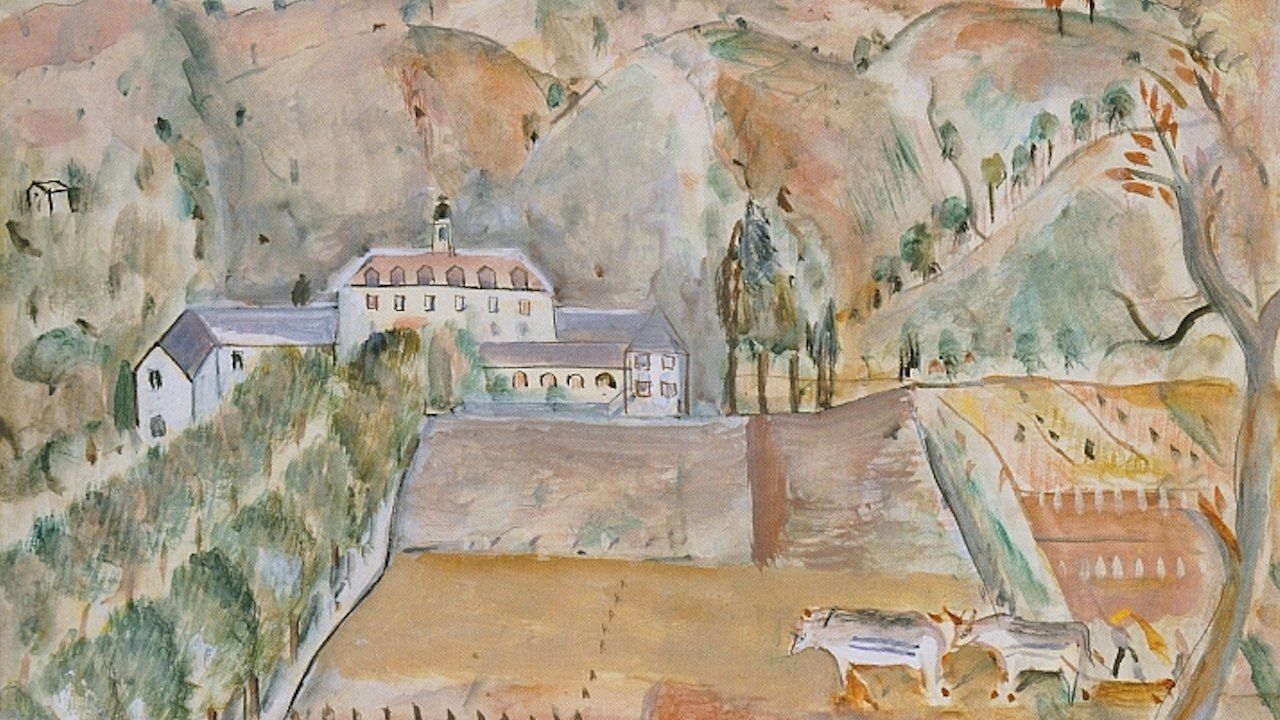

Roman Land (1928) by David Jones

PROLOGUE

In the first part of this lecture we examine five key ideas which undergird David Jones’s artwork and writing. Parenthetically we should note that his artwork filled the decades of the thirties and forties, but from the late thirties on he turned more and more to writing as his key format, with forays into calligraphic paintings he called “inscriptions.”

The five key ideas, in sequence, are palimpsest, sign and sacrament as a unit, anamnésis, Cymreictod (Welshness), and hiraeth. These will be defined as we proceed, but if you are unfamiliar with several of them, here are brief definitions. A palimpsest is a work that has been scraped off and written over, and thus refers to layers of meaning below a surface. Anamnesis is the remembrance of Christ and of the people in the eucharistic prayer in Christian liturgy. Hiraeth is a word that is very hard to translate from Welsh; it literally means “a horizon that keeps receding,” and so it is used of the yearning one feels for a homeland.

The second part of the lecture, tomorrow afternoon, will presuppose these five ideas and underscore how David Jones created a beloved home for himself in space and time apart from a specific locale. To do this we will use two key writings as a prism to focus our attention. Lastly, we will turn to ourselves and explore how his creation challenges and informs our lives today.

I. INTRODUCTION

David Jones was a man on a mission, but he was troubled that his mission might not be achievable. He lived, as he said, at the end of an era and he constantly pondered how his work might be able to inform the lives of others. With his friends he discussed this end of the era as what he called “the break,” meaning the end of a confluent view of culture that embraced Christianity and nation as one history, and in which the material realm expresses the spiritual realm as central focus. Such a unified life seemed impossible when “…it is easy to miss Him (Christ) at the turn of a civilization” [1].

At the end of the first part of his magisterial essay, “The Myth of Arthur,” David Jones writes: “It is an idle question whether this change (in historical circumstances) is a retrogression or an advance, for man does not determine these things, nor the temper of the world into which he is born. He can at best suffer the circumstances of his nativity and tradition. But there is something which he does determine, which it is his nature to fulfil.…he can, he must, and does, make a song about it” [2]. He continues: “We do not know what songs may yet be possible or what shape our myth will take, but it looks as though the waste land before us is extensive; and it is certain that in our anabasis across it we shall have reason to keep in mind the tradition of our origins in both matter and spirit” [3].

These lines not only echo Jones’s approach to his life and times, but are also indicative of our times and may prove instructive to us in ways he might well have imagined, given his fertile mind and understanding of history, tempered as it was through his reading of Spengler’s work, The Decline of the West [4]. Jones’s interest was primarily in the precision and depth of Spengler’s documentation, although he agreed with Spengler’s overall concept of the historical movement from culture to civilization—understood through the prism of the Arts and Crafts Movement and Eric Gill’s tutelage—as a negative influence in the Western world. For Spengler, civilization is grounded on utility and technocracy, whereas culture is the sum total of a people’s art, history, and wisdom (Jones disagreed with Spengler in specific points, however, e.g., that painting in the modern age had become unimportant and Spengler’s “pessimism” on metaphysical grounds) [5]. He was concerned that a “new type of civilization” has destroyed these older traditions, and the cultures they address no longer exist [6]. For Jones, we are in exile within our own lands insofar as we identify with the traditional history and its inner expressions [7]. Jones seems intent to be a custodian of these lost connections [8].

Jones wrote a review of the book Arthurian Torso, Charles Williams’s last writing which, because of his demise, C. S. Lewis had to finish [9]. The title honored Williams, who had intended to call it The Figure of Arthur [10]. In his review Jones is both generous with praise for Williams’ poetic approach to the text, which he considers far superior to Tennyson’s The Idylls of the King, of which Jones comments: “all through Tennyson’s Idylls the Arthurian story is pulling against nearly everything that Tennyson wants to say. There is no such tension in Williams’s Arthuriad” [11].

Jones’s appreciation of Williams stops short of full affirmation, however, because Williams, by his own admission, did not take into account the Welsh origins of the Arthurian body. This leads us to a major characteristic of Jones’s life which is abundantly, almost exhaustively, clear under three heads in his essay “The Myth of Arthur”: 1) the extraordinary degree to which Jones was committed to the Welsh homeland; 2) the early songs of the Welsh bards about Arthur, e.g., Culhwch ac Olwen, Preiddeu Annwn, and Y Gododdin; and 3) the early Romano-British history of the British Isles as represented in such historiography as Geraldus of Wales. These three make up a texture, if you pardon a shift of imagery, a woven fabric into which Jones fitted himself and to which he was committed as the story of his own life. At the same time, Jones was himself the weaver of that fabric, for as he himself says in other words, the artist must find a way to work with the myth, the legend, and the history from which he emerges and to present that in a way people today can understand.

Like many an autodidact, David Jones knew no boundaries to his scholarship. No one at Oxford or Cambridge put limits on his investigations, and consequently he was able to draw freely upon the wellsprings of his culture on many levels, both historical and legendary. His sources are, however, quite clear: he is committed overall to the history of Europe, but more specifically to the history and legend and literature that was the foundation of the British Isles.

II. PALIMPSEST

Before David Jones was a writer, he was a unique artist. From 1930-35 he belonged to a group of Modernist painters known as the Seven and Five Society, but he resigned because his own vision did not coincide with the restraints the group chose as their artistic statement. In paleography, a palimpsest is a page of text that has been scraped off and overwritten with new text; this has become a term to describe layers of thought and writing. If you examine his artworks, you will see that they are a kind of palimpsest, a layering of myth, history, legend, and liturgy. In Jones’s paintings we see underlying themes lightly painted in, often with pen outlines to indicate them, and then the layers that go over them. They exhibit both a transparency and a delicacy like lace. David Jones’s paintings cannot be grasped intellectually or aesthetically in an instant; they demand attention. In David Bentley Hart’s words, Jones

belonged to that very rare class of visionary artists who, like Blake, produce works that seem to reach into other realms of being. He seemed to have discovered worlds of mythic, religious, and aesthetic meaning that had never before been revealed, but that nevertheless felt as ancient and familiar as this world; and, also like Blake, he explored those other realms through both literature and the visual arts [12].

If we turn to his writing, we’ll find that same palimpsestic quality. For example, his first major book, entitled In Parenthesis, interweaves its tale of his experience in the Great War with Roman Legionary experience two thousand years before, and with quotes from Shakespeare and the Bible. The speech of Dai Greatcoat, which is a rehearsal of significant events, a palimpsest across the whole scope of British history, forms the centerpiece of the book as a tour de force [13]. There is overlap with myth, as at the poignant end of the book when the Queen of the Wood returns with garlands for the fallen soldiers of the 38th Welsh Regiment:

Some she gives white berries

Some she gives brown

Emil has a curious crown it’s

Made of golden saxifrage.

Fatty wears sweet-briar,

He will reign with her for a thousand years [14].

The overall symbolism of In Parenthesis is well-known to people of Welsh background: the noble dignity of the losers, shown by allusions to the Arthurian battles of Catraeth and Camlann. Jones quotes his other favorite historian, Christopher Dawson, in the preface to In Parenthesis: “it is the conservatism and loyalty to lost causes of Western Britain that has given our national tradition its distinctive character…” [15]. Quotes from Y Gododdin, Aneirin’s poem about the battle of Camlann at which Arthur is defeated, festoon each chapter head of In Parenthesis.

Jones referred to himself as a sign-maker [16]. But he lamented that “it may be that the kind of thing I am trying to make is no longer makeable in the way in which I have tried to make it” [17]. In Parenthesis, for example, yields its depth only to those who are willing to explore the palimpsest of myth, legend, and history as presented by Jones. For this reason, this book, which is indeed an epic poem, had to have footnotes; and for the contemporary American reader, even these are far less than needed for full comprehension, because Jones has wrapped himself in a garment woven of the rich colors and textures of a particular history, that of Britain and specifically of Wales [18]. This legendary history, as palimpsest, bears meaning and significance to the life of whoever rehearses and embodies it [19].

The same is true of his other great epic The Anathémata. Anathémata are “the things laid up from other things…things set up, lifted up, or in any manner offered to the gods” [20]. Jones knew the same word could be used for condemnation: the anathema of the Ecumenical Councils against various heretical and schismatic movements is a proscription, a curse, a casting out of things that have been improperly or inaccurately “laid up” and “offered to the gods.” Jones sets out to make sure that these things laid up are set forth in a proper manner, a manner worthy of the great era of Christendom which he was representing in a bittersweet age, a manner that will show forth the palimpsestic layer upon layer of references, whether obscure or evident, which lay at his disposal; he is himself the repository for the history and myth he wishes to recreate. Our poet knows (once again) that “it is easy to miss him at the turn of a civilization” because of the shift from culture to civilization (Spengler), from art to the utile (Gill), from Christendom to secularism. Yet Jones will nevertheless persevere bravely in the effort to discover and present that Lord.

III. SIGNS AND SACRAMENTS

Nearing his seventieth birthday, David Jones was interviewed in his one-room flat in London by Saunders Lewis, his old friend and leader of the movement for Welsh nationalism and language. Jones’s painful shyness and difficulty with expressing himself orally is noticeable in this BBC program, but the very end is significant. Lewis says to Jones, “Here in this room you are surrounded by all the reminders of the context of your life…and with these paint pots and brushes and everything you keep your contact with the earlier painter.” Jones replies, “Yes, with the whole world of sacraments and signs” [21]. Sacraments and signs are his natural homeland as an Anglo-Welsh man and as Catholic Christian.

The epigraph that Jones chose for his book In Parenthesis is a quote from the Catholic writer Maurice de la Taille: “He placed himself in the order of signs” [22]. Christ entered the human condition, where sign and sacrament are possible as a surplus of meaning. The flowers given to one’s lover are not merely material flowers; they bear the significance of love. They are a sign. By entering the human condition, Christ placed Himself in the order of signs. Sign is foundation of sacrament: this bread and wine bear a surplus; they are at once the body and blood of Christ. To recall Augustine, the sacrament is a “visible sign of invisible grace.” As Jones writes, “A sign must be significant of something, hence of some ‘reality,’ so of something ‘good,’ so of something that is ‘sacred’” [23].

IV. ANAMNESIS

Jones connects this sign-making of Christ with the concept of anamnesis that is central to the working agenda of The Anathémata, the whole of which emerged from contemplation on the anaphora of the eucharist. Jones had read Dom Gregory Dix’s Shape of the Liturgy, and he was deeply impressed with the idea that the whole life and ministry, passion and sacrifice of Christ are given to the faithful so that they may be present with these realities of the faith, transcending time and space in Eucharist. Indeed, he quotes Dix as follows: “in the scriptures of both the Old and New Testament anamnesis and the cognate verb have a sense of ‘recalling’ or ‘re-presenting’ before God an event in the past so that it become here and now operative by its effects” [24]. Anamnesis is not only the heart of Jones’s theology and his concept of art; it informed the whole of his life.

In his essay “The Arthurian Legend,” Jones made it clear that his entire approach to art is grounded in anamnesis and sacrament, which for him means that “this thing may be made other” [25]. In his words, what was then must be made now; history must be relevant to the present, and in such a way it will inform the future. Jones called this view “transubstantiated actual-ness.” Tom Dilworth relates an epithet from Jones’s early childhood apposite this adult stance. David overheard his mother ask their doctor, a Yorkshire Quaker, why Friends had no sacraments. The doctor replied, “But surely Mrs. Jones, the whole of life is a sacrament.” As Dilworth remarks, Jones agreed with these words throughout his life [26].

The “transubstantiated actual-ness” of history, myth, and legend informs all of Jones’s writings. This is especially true of the major works In Parenthesis, The Anathémata, and the latter’s literary predecessor The Sleeping Lord. It is, furthermore, the engine that drives his essay “The Myth of Arthur.” In practice this means that Jones used and mined and valorized the witness of the past as he understood it to inform his present thought and work. But this usage was not grounded in nostalgia; it was based on something other.

V. CYMREICTOD / WELSHNESS

This brings us to the important idea, in Welsh consciousness, of hiraeth and cymreictod. Cymreictod / Welshness may be defined as an attraction to or sensibility about matters Welsh, whether artifacts or history or myth. The theme undergirds both Jones’s prose and poetry, especially the short collection, The Sleeping Lord, which his friend Rene Hague called “the most Welsh of all David’s writings.”

The term Welshness embraces the Welsh culture and, to a great extent, immersion in it. For many people this immersion begins with language. As one writer put it, “The Welsh language gave me roots and a sense of direction, and it also set me apart from the crowd” [27]. Welsh theologian A. M. (“Donald”) Allchin remarks on the importance of language as a binding force, particularly in small nations [28], a notion with which Jones would concur, as may be gleaned from any exploration of his poetry, deftly sprinkled as it is with key Welsh words.

Part of Welshness is a sense of connection to the land. American John Dressell, who repatriated to Wales as an adult, writes: “Wales saturates the consciousness with a sense of time. The Welsh and their predecessors have continuously occupied this piece of peninsular earth in the far west of Britain for so terribly long. The physical reminders of this are everywhere” [29].

Another writer, Bobi Jones, says, “Writing in Welsh means to be in the middle of the great human struggle… a writer’s ‘mother’ tongue, in the literal sense, is not necessarily his best medium for his creative work—but that language which captures his heart and imagination ” [30]. He connects Welshness directly to the language, even if the language is not naturally learned or known as first language; “mother’” tongue means that one embraces the language.

David Jones downplayed his knowledge of the Welsh language in a number of places; it was not native to him, but he strove from the age of sixteen to study and understand it

[31]. His notes on Welsh in his books indicate that he had a better comprehension than he credited himself with, though he was sad that he could never pronounce Welsh like a native speaker. Surely he knew Tolkien’s inaugural O’Donnell Lecture at Oxford on 21 October 1955 in which Tolkien said,

More than the interest and uses of the study of Welsh as an adminicle of English philology, more than the practical linguist’s desire to acquire a knowledge of Welsh for the enlargement of his experience, more even than the interest and worth of the literature, older and newer, that is preserved in it, these two things seem important: Welsh is of this soil, this island, the senior language of the men of Britain; and Welsh is beautiful [32].

Time and place and land connect through language, as Emyr Humphreys points out: “To each mystery there must be a key; but the key of keys is the original language which hallows every hill and valley, every farm and every field with its own revered name ” [33]. The beauty of a place lies in the layers of meaning a name gives it, as in the Bible when Abram calls the altar he sets up Peni-El, for there he has seen “the face of God.”

Welshness may be an attitude, a leaning in the direction of a culture that one embraces, so that John Davies can end his study The Celts by saying that “the Celts are those who choose to see themselves as Celts” [34]. Welshness is an ongoing process by which one relates to the present on the basis of a felt love for Wales and things Welsh. This was clearly characteristic of David Jones from his youth [35]. He felt himself to be a part of a long history “by blood or inclination” [36].

VI. HIRAETH

The other concept / feeling / emotion is hiraeth, a word considered untranslatable, but often described as “homesickness,” “longing,” or “nostalgia.”

Y mae hiraeth wedi ‘nghael

Rhwng fy dwyfron a’m dwy ael;

Ar fy mron y mae yn pwyso

Fel pe bawn yn famaeth iddo.

Hiraeth has got me between

my two breasts and my two brows;

it presses on my breast

as if I were nurse to it [37].

Hiraeth is more than longing. It is a combination of longing, nostalgia, obsession for a thing, a place, a person or state of being that one might have had in the past, or perhaps a dream about the future. One can certainly suffer hiraeth without Welshness. Jones is clearly concerned with Welshness but not with hiraeth, although there is overlap between these emotional and psychological states. Nostalgia is a longing for the past, but hiraeth is not exactly this: it is a longing for a present that is unattainable for one reason or another, usually beginning with physical separation.

Wales, Wales, my mother’s sweet home is in Wales;

Till death be pass’d my love shall last,

My longing, my hiraeth for Wales [38].

Hiraeth can be a longing for the past, including the mythic or legendary past. The poet Waldo Williams captured this in his work, “Remembering”:

The achievement and art of early generations,

Small dwellings and great halls,

The fine-wrought legends scattered centuries ago,

The gods that no one knows about by now [39].

Finally, hiraeth can be a longing for the Celtic Otherworld or for Christian paradise, which diverse elements Dora Polk notes are often blended together as a singular concept.[40]

Hiraeth was keenly felt by those who were religious or economic exiles from Wales.[41] In Jones’s reminiscences about his childhood, this aspect of hiraeth seems to be absent. Trips to Wales were infrequent and we get no sense that his Welsh father wanted to return, which might have inspired the sense in Jones that he could be Welsh outside Wales.

Hiraeth never seems to be concrete in the same sense as cymreictod. Pamela Petro writes, “One of the characteristics of true Welsh Hiraeth, that differentiates it from plain old homesickness, or nostalgia, is the consciousness of home as the home of the others.” It is, in her words, “a deep—and at heart deeply creative—longing for something unattainable that may exist only in the imagination, possibly, probably, beyond place or time” [42]. In this sense, perhaps, Jones exhibits hiraeth despite the fact that he never wished to move to Wales but remained in London for most of his life. Jones knew that the Anglo-Saxon word from which the name Wales was derived means “foreigner” or “outsider,” as though one were exiled within one’s own home by the fiat of conquerors [43]! That known, Jones would have been content as an outsider who is at one and the same time an insider, to know a hiraeth and a Welshness that could be deeply known inside yet experienced without actual residence.

These five key ideas—palimpsest, sign / sacrament, anamnesis, Cymreictod, and hiraeth—form a texture within which David Jones lived and moved and had his being, as he expressed in his comment to Saunders Lewis or in his word that he might be Welsh “by blood or inclination.”

[1] David Jones,

The Sleeping Lord and Other Fragments (London: Faber & Faber Ltd., 1976), p.9.

[2] “The Myth of Arthur,” pp. 212-259 in Epoch and Artist (London: Faber & Faber, 1959), at p. 241.

[3] Idem, p. 242.

[4] Jones mentions this book many times in conversation with William Blissett, The Long Conversation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), pp. 12, 37 et passim.

[5] Cf. David Jones, The Dying Gaul (London: Faber & Faber, 1978), pp. 137ff. and p. 159.

[6] David Jones, Dai Greatcoat (London: Faber & Faber, 2008), p. 89.

[7] On the theme of exile and native, see esp. Jeremy Hooker, Imagining Wales: A View of Modern Welsh Writing in English (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2001), pp. 22-25.

[8] David Jones, The Anathémata (London: Faber & Faber, 1979), pp. 23ff. on the evocation of lost connections.

[9] “The Arthurian Legend,” pp. 202-211 in Epoch and Artist.

[10] Noted on p. 207 of the essay. Another suggested title was The Body of Arthur.

[11] Op. cit., p. 205.

[12] David Bentley Hart, “The Lost Modernist,” in First Things, March 2018.

[13] Ibid., pp. 79-83.

[14] David Jones, In Parenthesis (New York: Viking Press, 1963), p. 185.

[15] Ibid., p. xii. Italics mine.

[16] “Art and Sacrament,” in Epoch and Artist.

[17] Anathémata, p. 15.

[18] See “Autobiographical Talk,” in Epoch and Artist, pp. 27-31

[19] Anathémata, p. 40.

[20] Ibid., pp. 27-29.

[21] Full interview available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psQkOT7eNwE&feature=youtu.be

[22] Epoch and Artist, title page and p. 179.

[23] David Jones, Epoch and Artist, ed. Harman Grisewood (London: Faber & Faber Ltd., 1959), p. 157.

[24] “Mabinog’s Liturgy,” pp. 182-221 in Anathémata, cited at footnote 1, p. 205; italics in the text; quote from Dom Gregory Dix, The Shape of the Liturgy, p. 161.

[25] “The Arthurian Legend,” pp. 210f.

[26] Thomas Dilworth, David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet (Counterpoint Press: Berkeley, 2017), p. 10.

[27] Sylvia Prys-Jones, “Coming Home,” in Davies, Oliver and Fiona Bowie, eds., Discovering Welshness (Llandysul: Gomer Press, 1992), p. 6.

[28] A. M. Allchin, “The Outer Loss shall be The Inner Gain,” in Davies and Bowie, 1992, pp. 16-18. Allchin corresponded with Jones on matters relating to the Welsh language and also religion. See also “Diversity of Tongues,” pp. 135f., in A. M. Allchin, Praise Above All: Discovering the Welsh Tradition (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991).

[29] Jon Dressell, “The Man Who Was Frisked of His China Rugby Ball,” in Davies and Bowie, 1992, pp. 26f.

[30] Bobi Jones, “Why I write in Welsh,” in Davies and Bowie, 1992, p.114.

[31] Dilworth, op. cit., p. 30.

[32] J. R. R. Tolkien, “English and Welsh,” O’Donnell Lectures at Oxford University, 1955. Originally published in Angles and Britons in 1963, and later in The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. (Get cita

[33] Emyr Humphreys, “Open Secrets.” This note was also sounded by Lady Charlotte Guest in her 1848 introduction to her translation of The Mabinogion (New York: Dover Reprint, 1997), pp. x-xi: Saxon names define the locality (hill, ford, etc) whereas Welsh names reflect an event “real or supposed” that happened on the spot.

[34] John Davies, The Celts (London: Cassell & Co., 2000), p. 187.

[35] Dilworth, op. cit., p. 15.

[36] Preface to In Parenthesis; cf. also Epoch & Artist, p. 36.

[37] Dora Polk, compiler, A Book Called Hiraeth: Longing for Wales (West Glamorgan: Alun Books, 1981), p. 13. This deeply expressive poem evokes hiraeth as of both the heart and the head, with the heart having the largest part in the emotion. Trosset shows this characteristic as indicative of Welsh personality, Trosset, 1993, pp. 151ff.

[38] Polk, 1981, p. 21.

[39] Ibid., p. 84.

[40] Ibid., pp. 120-122.

[41] Ibid., pp. 46ff. Parenthetically we might note that circling around the city of Philadelphia are about thirty-five communities with Welsh names, a sign of the hiraeth that Welsh Quakers experienced when they found refuge in William Penn’s colony that accepted those who were religious exiles.

[42] Pamela Petro, ‘Longing for Dylan’, Swansea Review (Spring, 2014). [online] Available at http://www.swanseareview.com/2014/pamelapetro.html

[43] His inscription entitled Hic jacet Arturus, which commemorates the death of Llewelyn, has the superscription cara wallia derelicta—dear Wales abandoned. David Jones, The Tate Gallery (Tate Gallery Publications, London, 1981), p. 137.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.