Council or Father or Scripture

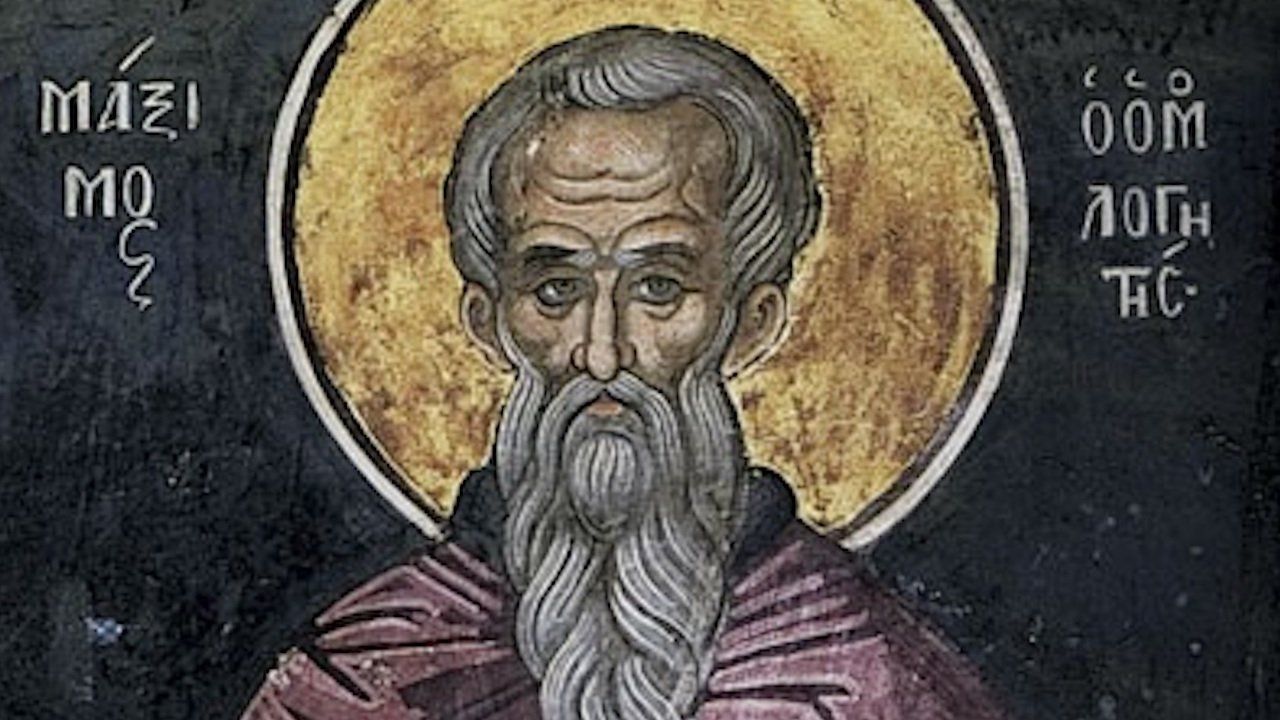

The Concept of Authority in the Theology of Maximus the Confessor

by Jaraslov Pelikan

Feast of St Lucillian of Byzantium

Anno Domini 2019, June 3

BY COMMON consent, St. Maximus the Confessor (ca. A.D. 580-662) must be regarded as the leading theologian of his era in the Greek East, probably in the entire church. In his history of the Byzantine Fathers, Georges Florovsky selected him as the only seventh-century figure deserving an entire chapter unto himself; Irénée Hausherr termed him “the great doctor of philautie [i.e., the love of self for the sake of God], doctor in the sense both of professor and of physician”; Hans-Georg Beck called him “the most universal spirit of the seventh century and probably the last independent thinker of the Byzantine church”; Werner Elert referred to him as “probably the only productive thinker of the entire century”; and Aldo Ceresta-Gastaldo identified him as “the most significant theologian of the seventh century.” But he seems to have acquired this standing very early. In the first part of the Doctrina patrum de incarnatione Verbi, which seems to have been compiled by an unknown “Anastasius” within a decade or two after the death of Maximus, he is quoted several times and is even referred to in the chapter headings (which may not be original) not only as “Abbot Maximus,” but as “Saint Maximus.” Indeed, the appearance of quotations from him in this extremely important florilegium has been the most significant evidence in the attempts to date the work.

These accolades to Maximus as original and independent would not, however, have seemed to him to be an unqualified compliment. What was required of a theologian was not that he be independent or productive or original, but that he be faithful to the authority of orthodox Christian dogma as this had been set down in Scripture, formulated by the Fathers, and codified by the Councils. Yet this did not mean that the mind of the theologian was to be put into suspended animation or to act as nothing more than a passive transmitter of what had been received. “The life of the mind,” in Maximus’s axiom, “is the illumination of knowledge, and this is derived from love toward God” (On Charity 1.9). In opposition to every species of pietism, he insisted that “the grace of the Holy Spirit does not effect wisdom in the saints without the mind that grasps it, nor knowledge without the power of the reason that is capable of it, nor faith apart from the fullness of conviction in mind and reason concerning future things” (Qu. Thal. 59). It was essential, even and especially in a theology that strove to be orthodox, to make precise distinctions among the possible meanings of words and phrases; otherwise the controverted issues would remain as confused after the debate as before it. The failure to make such distinctions was “often the cause of error” (Opusc. 25). It is this combination of orthodox dogma with a fides quaerens intellectum [faith seeking understanding] that makes Maximus so interesting; and because the honorand of this Festschrift [i.e., Florovsky] has, in his own unique way, managed to combine an orthodox fidelity to tradition with theological creativity, the concept of authority in the theology of Maximus would seem to be an appropriate subject of investigation for an essay in his honor.

Maximus consistently asserted that he, as a Christian theologian, was under authority. As he stated near the beginning of his exposition of the Lord’s Prayer, “what I am writing to you, as one who has been commanded to do so, is not what I reason out for myself … but what God wills” (On the Lord’s Prayer). And what God had willed and commanded was revealed to the simple and to the elite, in Sacred Scripture. It was “the servants of the Old and the New Testament, the holy patriarchs and the lawgivers and the leaders, the judges and the kings, the prophets and the evangelists and the apostles, through whom the water of knowledge has been drawn and restored again to nature” (Qu. Thal. 40). The lifelong study and “continuous meditation on the divine Scripture” was his own constant preoccupation and the course he urged upon his readers (Ascet. 18). It was, therefore, not permissible for anyone to refuse to believe what Scripture said. Rather, one was to heed its word; for “if it is God who has spoken and if He is uncircumscribed [ἀπερίγραφος] in His essence, then it is obvious that the word which has been spoken by Him is also uncircumscribed” (Qu. Thal. 50). Not only the authority, but also the perspicuity, of Scripture made it the arbiter of Christian doctrine. What it taught about the soul and the resurrection especially in 1 Corinthians 15, was so clear and intelligible that one did not need an interpreter to understand it—although in this case the clarity of Scripture was enhanced by its congruence with the insights of even the barbarians into the nature of things, without the aid of divine revelation (Epistle 7). The decisive authority in such controversies as that over the wills of Christ had to be “the dogmas of the Evangelists and Apostles and Prophets” (Pyrr.).

Yet the experience of these controversies, in which Maximus himself was engaged through most of his life, and the history of earlier controversies made it obvious that, inspired and clear though Scripture was, theologians could read and understand it in different, indeed contradictory, ways. “Those who do not read the words of the Spirit wisely and carefully” could fall into “many kinds of error” and had done so (Qu. Thal. 43). This happened when the reader, through ignorance or deliberate distortion, failed to observe the distinctness of the Scriptural way of speaking. “It is the custom of Scripture,” Maximus declared, “to explain the ineffable and hidden counsels of God in a bodily manner, so that we might be able to know divine matters on the basis of words and terms that are cognate; for otherwise the mind of God remains unknown, His word unspoken, His life incomprehensible” (Qu. Thal. 28). Anyone who sought to grasp the meaning of the Scriptures had to pay very careful attention to this way of speaking. He also had to observe that a word or a proper name used in the Bible was multiple in meaning [πολύσημον], as was evident, for example, in the etymology and exegesis of the name Jonah (Qu. Thal. 64). In the story of Jonah, as throughout its narratives, Scripture consistently placed its real and spiritual meaning “before what it tells in historical accounts [πρὸ τῶν ἱστοροθμένων],” but this was visible only to those who looked at it with sound vision and with healthy eyes (Qu. Thal. 17).

Above all, of course, as the words of Christ about Jonah in Matthew 12:39-41 make clear, this characteristic of Scripture was important for a proper understanding of what it had to say about Christ and about salvation. “Our Savior has many names” (Ambig. 46), and there were many methods of contemplating Him through the types and symbols of the natural world as these were employed in the Scriptures. For while it was true that “the prophetic charisma is far inferior to the apostolic” (Qu. Thal. 28), the writings of the prophets were replete with testimony to Christ. The words of Hosea 12:10 about the visions of the prophets meant that “by means of symbols God has planted beforehand variegated prefigurations of His wondrous coming in the flesh” (Qu. Thal. 62). It was the task of a faithful exegete to find these symbols and to apply them to the coming of God in the flesh. He had to understand Scripture both according to the letter and according to the spirit; to pay attention only to the letter was to be blind to its full meaning (Qu. Thal. 32). And so “whoever pays attention only to the letter of Scripture finds only the meaning that is appropriate to nature” (Qu. Thal. 63). For example, the historical figure of Zerubbabel never held a stone in his hand with the seven eyes of the Lord on it, as described in Zechariah 4:10; and therefore, “because it is utterly impossible for this to stand as it reads [χατὰ τὴν λέξιν],” it was necessary to look for a deeper meaning (Qu. Thal. 54). This deeper meaning could be called the allegorical or the tropological: allegory dealt with inanimate objects, such as trees and mountains, while tropology dealt with parts of the human body, such as the eyes and the head (Qu. dub. 8). There were some exegetes who “industriously stick only to the letter of Scripture,” but those who loved God had to concentrate on the spiritual meaning, because the word of truth meant more to them than the mere letter of what had been written” (Qu. Thal. 52). It was, then, axiomatic that anyone who did not penetrate to the spiritual meaning of Holy Scripture would derive from it only the natural law rather than the law of grace, by which alone true divinization was conferred (Qu. Thal. 65). Thus, as a brief note by the late Polycarp Sherwood pointed out, Maximus regarded the spiritual understanding of Scripture as essential to its authority (“Exposition and Use of Scripture in St. Maximus as Manifested in the Quaestiones ad Thalassium, ” Orientalia Christiana Periodica, 24 [1958], 202-207).

The Quaestiones ad Thalassium, which still have not received the “thorough doctrinal analysis” for which Father Polycarp had called in an earlier essay, were written in response to a request for the clarification of various biblical passages that seemed obscure (Qu. Thal. pr.). Therefore Maximus’s defense of the spiritual meaning, largely as set forth in that treatise, did not always make explicit the hermeneutical presupposition which protected allegory and tropology from the caprice of the individual exegete, namely, as Maximus said near the end of the Quaestiones ad Thalassium, that “the precise knowledge of the sayings of the Spirit has been disclosed only to those who are worthy of the Spirit,” the Fathers of the Church and those who were faithful to that tradition (Qu. Thal. 65). For the lamp of Holy Scripture was inseparable from the lampstand of theCatholic Church (Qu. Tha. 63). Other writings of Maximus, especially of course those called forth by the Monenergist and Monothelite controversies, spelled out this presupposition in greater detail. In one of his last works, the Relatio motionis of May 655, he made it clear that since, according to 1 Corinthians 12:28, Christ Himself had instituted not only Apostles and Prophets, but also Teachers, in the Church, “we are taught by all of Holy Scripture, by the Old and the New Testament, and by the Holy Teachers and Councils” of the tradition (Rel. mot. 9). The Apostles had instructed their successors, and these their successors in turn, “the divinely guided Fathers of the Catholic Church [θεόχριτοι τῆς χαθολιχῆς ἐχχληςίας πατέρες] (Opusc. 15). To be sure, what the Fathers taught did not come “from their own resources [οἴχοθεν],”but had been drawn from the Scriptures (Pyrr.). But anyone who took it upon himself to expound “the entire teaching” of Scripture could not do so without the guidance of those who had developed the exact understanding of the mysteries of Scripture (Ambig. 37). This guidance in the understanding of the sublime teaching of Scripture came from “the mystae and the mystagogues” who had exercised themselves in it (Ambig. 67). Monenergism and Monotheletism, therefore, could be denounced as lacking the authority either of the word of God or of the Fathers (Opusc. 9), “in accordance with the tradition both of the sacred oracles and of the patristic teachings” (Opusc. 20). The authority of Scripture, then, was the authority of a properly interpreted Scripture, viz., a Scripture interpreted according to the spiritual sense and in harmony with the interpretation of the patristic tradition.

So intimate was the connection between Scripture and the Fathers that Maximus could quite unabashedly cite as his authorities “the holy Apostle Paul and … Gregory of Nazianzus, the great and wondrous teacher” (Ambig. 71). The difference between the apostle and the theologian seems to have been one more of degree than of kind. The fathers and theologians of the church could have spoken on many questions that they did not discuss, for there was a “grace in them” that would have authorized them to do so, but they preferred to keep silence (Qu. Thal. 43). The sayings of Gregory the Theologian and of Dionysius the Areopagite were “not their own, but belong to Christ, in accordance with the grace” conferred upon them (Ambig. pr.). Maximus cited the authority of “our holy fathers and teachers,” but immediately added: “or, rather, of the truth that speaks and has spoken through them” (Ambig. 42). And so the attribute “inspired by God” [θεόπνεθστος], used in the New Testament only once and applied only to the Scriptures of the Old Testament, could now be applied also to “the inspired fathers” as they explained the meaning of prayer (Or. dom.). The attributes and epithets attached to the names of individual church fathers are a significant index to Maximus’s estimate of their special grace and inspiration. Athanasius was “this God-bearing [θεόθορος] teacher” (Ambig. 10); Basil the Great was “the great eye of the church,” meaning perhaps “the leading light” (Pyrr.); Clement of Alexandria was “the philosopher of philosophers” (Pyrr.);Dionysius the Areopagite was “the one who truly spoke of God, the great and holy Dionysius” or even “the revealer of God [θεοφἀντωρ]” (Ambig. 7, 41; Gregory of Nazianzus was not only a “God-bearing teacher,” as was Athanasius, but his sayings were “most divine” (Ambig. conc.). Even some of the Latin fathers came in for recognition. Maximus had discovered through his contacts with the Latins that “they are not as able to express their mind in another language and speech as they are in their own” (Opusc. 10). But in his response of 646 or 647 to the Ekthesis of Emperor Heraclius, with its use of the disastrous formula of Pope Honorius about “one will,” Maximus was able to invoke the authority of the Ad Gratianum of Ambrose; Leo the Great, because of the connection between his Tome and the decree of Chalcedon, was “the exarch of the great church of the Romans, Leo the all-powerful and all-holy” (Opusc.15).

These inspired and holy fathers of the Catholic Church, Eastern and Western, were the norm of Christian doctrine and the standard of Christian orthodoxy. When Maximus’s opponent Pyrrhus asserted that the sayings of the fathers were “the law and canon of the church,” Maximus could only agree, declaring that “in this, as in everything, we follow the holy fathers” (Pyrr.). To other opponents in the christological controversies he proclaimed: “First let them prove this on the basis of the determinations of the fathers! … If this is impossible, then let them leave these opinions behind and join us in conforming themselves to what has been reverently determined by the God-bearing fathers of the Catholic Church and the five ecumenical councils” (Opusc. 9). “The orthodox doctrine of the holy fathers” had been handed down by tradition to the true churches of God (Opusc. 16). A wise and orthodox teacher of traditional dogma was like a lantern, illuminating the dark mysteries which were invisible to many; this light was “the knowledge and power of the patristic sayings and dogmas” (Qu. Thal. 63; Opusc. 7). For his ascetic instructions, Maximus relied not on his own thought, but on the writings of the fathers, which he compiled for the edification of his brethren (Carit. pr.). When ascetics forsook “the way of the holy fathers,” they became deficient in every spiritual work (Ascet. 26). “Let us,” he said in summary of his dogmatic position on Christology, “guard the great and first remedy of our salvation—I am referring to the beautiful heritage of the faith—confessing with soul and mouth in confidence, as the fathers have taught us”; and he followed this with an extensive paraphrase of the Nicene Creed, directed to the new issues that had arisen (Ep. 12). Or, as he defined his position more fully in response to Theodore, a deacon of Constantinople: “We do not invent new formulas, as our opponents charge, but we confess the statements of the fathers. Nor do we make up names according to our own ideas, for this is a presumptuous thing to do, the work and invention of a heretical and deranged mind. But what has been understood and stated by the saints, that we reverently adduce as our authority” (Opusc. 19).

But as it was not enough to cite the authority of Scripture when the orthodox and the heretics were both claiming that authority, so it really would not do simply to affirm that one stood with the orthodox tradition of the fathers in their interpretation of the faith on the basis of Holy Scriptures when both the orthodox and the heterodox were claiming this authority as well. The difficulty of citing patristic authority took two forms. Such an exhortation as “Let us reverently hold fast to the confession of the fathers” (Opusc. 7) seemed to assume, by its use of “confession” in the singular together with “fathers” in the plural, that there was readily available a patristic consensus both on the doctrines with which the fathers had dealt in controversy and on those over which debate had not yet arisen. The existence of such a consensus became problematical during the conflicts over the energies and the wills of Christ. “With a loud voice the holy fathers …, all of them everywhere, confess and steadfastly believe in an orthodox manner” about the Trinity and the person of Christ (Opusc. 7). But Dionysius had failed to anticipate later controversy when he spoke of “one theandric energy” in Christ (Ambig. 5). And what was one to do if within this supposed patristic consensus a father was found to speak of one will in God and in the saints, which would appear to imply one will in the incarnate Logos? This, Maximus replied, had to be taken to refer not to the will in the sense in which it was being debated, but to that which was willed; the former was present essentially, the latter was external to the will. Therefore the fathers were speaking “in a nontechnical and inexact sense [χαταχρηστιχῶς]” (Pyrr.). It was harsh, indeed it was unthinkable, to suggest that Athanasius and Gregory of Nazianzus could be in disagreement (Ambig. 13). When it appeared that there was a contradiction between two passages in Gregory, closer study would show “their true harmony” (Ambig. 1). Those who, “like thieves,” sought contradictions or errors in the fathers were to be dealt with by precise distinctions among various uses of the same word (Opusc. 7).

The other problem in the argument from patristic tradition came from the opposite direction: the literal insistence on the ipsissima verba [the very words] of the fathers and of the councils, and the refusal to go beyond these even in response to new challenges. Thus Theodore of Constantinople declared that “every formula and term not found in the fathers is an innovation,” and that therefore those who spoke of “two wills corresponding to the two natures” when the fathers had not done so were “inventing their own novel doctrine in opposition to the name of the fathers” (ap. Opusc. 19). Likewise, Maximus’s opponent in the debate of 645 in Africa, the deposed Patriarch Pyrrhus, joined in asserting the principle: “Let us simply be satisfied with what has been said by the councils, and let us speak neither of one will nor of two wills” (ap. Pyrr.). Maximus shared with all theologians who claimed to be orthodox an aversion to “innovation" [χαινοτομία], which was tantamount to “an emptying of the gospel” (Ep. 13). The orthodox faith was necessary for salvation; it was the basis both of hope and of love, neither of which was possible without it (Ep.12). Persons who taught falsely might be forgiven as persons, but the false teaching had to be anathematized (Pyrr.). But this did not imply that orthodoxy was to be identified with archaism. For example, the decree of Chalcedon had introduced the phrase “in two natures,” which had not been used in the definition of Nicaea. Did this mean that the fathers at Chalcedon were guilty of innovation? Of course it did not (Opusc. 4). All the fathers after Nicaea and all the orthodox councils had, by their additions of phraseology, not set down a new and different definition of the faith in comparison with the faith of the 318 fathers of Nicaea, but had reaffirmed the Nicene faith in opposition to those who were distorting it to suit their own ideas (Opusc. 4). Not all dogma was expressed in the decrees of Nicaea or of any council, and a literalistic insistence on the text of its decrees would have prevented the subsequent councils from replying to new heresies (Pyrr.).

What made a council orthodox, therefore, was not its repetition of the orthodox formulas of its predecessors. Rather, “the reverent canon of the church acknowledges as holy and authoritative those councils which the orthodoxy of dogmas has attested” (Disp. Byz. 12). There were criteria in canon law for determining whether or not a council was legitimate, and Maximus was able to invoke these (Pyrr.). Elsewhere he cited the authority in ecclesiastical matters of “our most reverent emperor and the most holy patriarchs, those of Rome and of Constantinople” (Ep. 12). Writing from Rome in 649, Maximus had special praise for “the most holy church of Rome,” whose “confession of faith” was acknowledged by all men, together with“the holy dogmas of the fathers” and the six councils (presumably Nicaea, Constantinople I, Ephesus, Chalcedon, Constantinople II, and the so-called Lateran Synod of that year) (Opusc. 11). The “keys” in Matthew 16:18 meant “the orthodox faith and confession” held by the Roman church (Opusc. 11). Elsewhere Maximus could cite this saying of Christ to Peter without explicitly referring to Rome, but not without referring to “the reverent confession, against which the wicked mouths of the heretics, gaping like the gates of hell, will never prevail” (Ep. 13). Peter was “the summit of the apostles, … the great foundation of the church,” and “the head of the apostles” (Qu. Thal. 27 and 61). The treatment of the primacy of Peter by Maximus and by other early Byzantine theologians suggests the possibility that Francis Dvornik’s revision of conventional opinions about the notion of apostolicity should itself be revised; for not only do “accommodation to the civil administration and apostolic origin” combine in the argumentation (Dvornik, The Idea of Apostolicity in Byzantium and the Legend of the Apostle Andrew, p. 50), but the orthodoxy of Rome’s position in doctrine is regularly invoked as a proof of its special apostolic standing and as a vindication of the promise in Matthew 16:18.

Such, then, was the structure of authority in the theology of Maximus: the teaching “of a council or of a father or of Scripture” (Opusc. 15), but in fact of all three in a dynamic interrelation by which no one of the three could be isolated as the sole authority. Scripture was supreme, but only if it was interpreted in a spiritual and orthodox way. The fathers were normative, but only if they were harmonized with one another and related to the Scripture from which they drew. The councils were decisive, but only as voices of the one apostolic and prophetic and patristic doctrine. Yet this schematization of Maximus’ teaching would not do him justice if it did not include one additional element, which reached beyond this argumentum in circulo. In a remarkable passage in his Ambigua, Maximus raised, but left to “wise men” to answer, the question why “if this dogma [of θἐωσις] belongs to the mystery of the faith of the church, it was not included with the other [dogmas] in the symbol expounding the utterly pure faith of Christians, composed by our holy and blessed fathers” (Ambig. 42). The symbol had declared that the Son of God came down “for the sake of us men and for the purpose of our salvation,” but it had not specified the content of that salvation as healing, forgiveness, and divinization. Yet this content clearly belonged to the faith and doctrine of the church. But dogma was not very well equipped to define it; its definition belonged more properly to the worship and piety of the church. “This release from all evils and shortcut to salvation, the true love of God with understanding”—this was, Maximus declared, “a worship that is true and genuinely acceptable to God” (Qu. Thal. pr.). For it was through worship that the church and its theologians acknowledged “theological mystagogy,” which transcended the dogma formulated by councils (Qu. dub. 73). Here it was also that one came to see how “every word of God written for men according to the present age is a forerunner of the more perfect word to be revealed by Him in an unwritten way in the Spirit” (Ambig. 21). And finally, the true fathers in the faith were those who, like Dionysius the Areopagite, taught that “negative statements about divine matters are the true ones” (Ambig. 20). Therefore “who knows how God is made flesh and yet remains God? … This only faith understands, adoring the Logos in silence” (Ambig. 5). Beyond the teaching “of a council or of a father or of Scripture” stood the authority of this reverent and orthodox but apophatic worship: “A perfect mind is one which, by true faith, in supreme ignorance knows the supremely Unknowable” (Carit. 3.99).

*Originally published in

The Heritage of the Early Church: Essays inHonor of the Very Reverend Georges Vasilievich Florovsky, edited by David Neiman and Margaret Schatkin (Rome: Pont. Institutum Studiorum Orientalium,1973), 277-288.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.