Commemorating Armistice / Veterans Day

An Evening of Film & Literature on the 101st Anniversary of the Cessation of Hostilities in the Great War

IT'S A JOY to welcome you all here tonight. If you’ll permit me, I’d like to share a few thoughts before we begin our literary readings . So, here we are on the eve of Veterans Day. The English word veteran comes from the Latin, vetus, for “old,” and suggests the accrued years of experience in a particular occupation, soldier or otherwise. But the special meaning of Veterans Day in the US has always been with an eye to honoring military veterans. As many of you know, Veterans Day was known as Armistice Day until 1954, and was inaugurated on Nov 10-11, 1919, to commemorate the cessation of hostilities between France and Germany in “the Great War” on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month (11 November 1918). That was 101 years ago, exactly.

World War I and its aftermath impacted western civilization in unprecedented ways, arguably ushering in the modern era, which in its early decades (and arguably still) is characterized by cultural disillusionment and hastened forces of secularization and despair. What we now know as PTSD was rampant, and effected an entire generation. After a catastrophe of such magnitude, some concluded that existence was meaningless, and found fleeting solace in the pursuits of hedonism. Yet some who lived through the Great War, and other wars since, responded differently: through a recuperation of traditional faith, historical consciousness, artistic endeavor, and honest work. Exactly 101 years later, how can we honor and remember the personal sacrifice, the loss of life, and the social aftermath of WWI and other wars, which are all a part of our inheritance? Especially pertinent for an event hosted by Eighth Day Institute is the question: how can reckoning with the significance of war help renew the cultural legacy of Christian civilization?

Ultimately, the impact of WWI cannot be fathomed. It was a war in which machinery utterly outpaced and outflanked strategy, leading to the tactically futile loss of millions of lives – an entire generation of European men. The cultural aftermath of WWI, or any war, cannot also be fathomed, insofar as each soldier’s experience of battle brings forward the most fundamental questions about life and death, truth and power, faith and doubt, beauty and suffering, and all these rippling through each veteran into the lives of those around them.

One paradox of war is that its purpose, end, and goal – its telos – is peace; or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that disagreements about what peace should look like – what partitions and rearrangements constitute an imagined state of peace – are what, in the most general of terms, motivate war. Another paradox of war is that it brings out both the best and the worst of people, facilitating in the most common of breasts either base depravity or selfless nobility – or a mixture of both. The words of war-time correspondent Chris Hedges are perhaps apropos here:

I learned early on that war forms its own culture. The rush of battle is a potent and often lethal addiction, for war is a drug, one I ingested for many years. It is peddled by mythmakers – historians, war correspondents, filmmakers, novelists, and the state – all of whom endow it with qualities it often does possess: excitement, exoticism, power, chances to rise above our small stations in life, and a bizarre and fantastic universe that has a grotesque and dark beauty. It dominates culture, distorts memory, corrupts language, and infects everything around it, even humor, which becomes preoccupied with the grim perversities of smut and death. Fundamental questions about the meaning, or meaninglessness, of our place on the planet are laid bare when we watch those around us sink into the lowest depths. War exposes the capacity for evil that lurks not far below the surface within all of us. And this is why for many war is so hard to discuss once it is over.

The enduring attraction of war is this: Even with its destruction and carnage it can give us what we long for in life. It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living. Only when we are in the midst of conflict does the shallowness and vapidness of much of our lives become apparent. Trivia dominates our conversations and increasingly our airwaves. And war is an enticing elixir. It gives us resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble. (Chris Hedges, War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, 3)

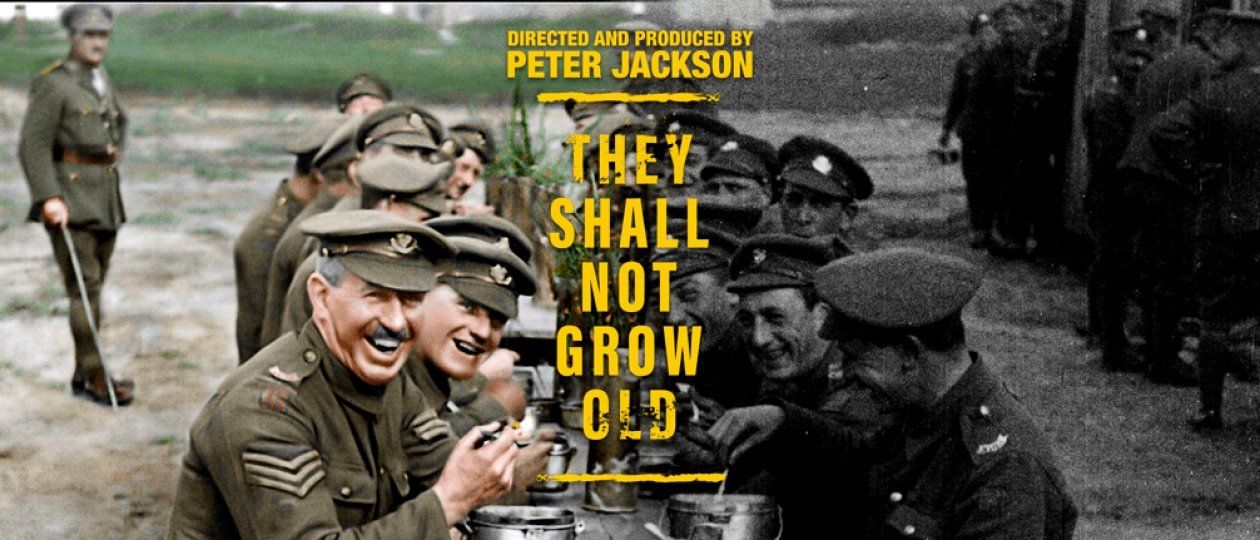

Surviving the battlefield, and finding purpose there, is one thing; picking up the pieces of society afterward are another. And there are those who did their best after WWI; among them, some of the authors whose works you’ll hear read from tonight. But there are many who fought in WWI and later wars whose thoughts or writings we’ll never know. Or maybe just barely. Only last night, I discovered brief anecdotal accounts of WWI from my wife’s great-grandfather, Donald Riggs, who was in the 40th US infantry division supporting the French army in the trenches in mid-to-late 1918. After the war, Riggs and others like him went back to their lives, forever changed, to a world that admittedly had difficulty knowing what to do with them. And there are many who never came home. And “they shall not grow old,” as tonight’s film title puts it.

But some did come home. Lately I’ve been steeping myself in the writings of the painter and poet, David Jones, who was a WWI veteran from the UK. Unlike many of his comrades, Jones did grow old – one year shy of four score years, dying in 1974. Other than – or perhaps even alongside – T. S. Eliot (if Eliot’s own thoughts on Jones’s work are taken into account), Jones may be the preeminent Christian modernist. His debut literary epic, In Parenthesis , has been called “The Iliad of WWI.” The excerpts from Jones on the handout are from his preface to In Parenthesis , which convey one artist’s perspective about war and its impact. His essay “Art in relation to War,” in posthumously published The Dying Gaul , is also to be recommended. Jones’ other long poetic work, The Anathemata , was described by W. H. Auden as “likely the best long poem in English of this century.”

In his poetic and artistic oeuvre, Jones mines the depths of Celtic, Roman, and Arthurian mythology to allusively recuperate a vision of history in which human beings, following the incarnational logic of creation, are most basically artists, that is, makers of signa. All made things can be, and historically have been, artifacts that exceed mere functionality and thus convey something of the gratuitious ( gratia = grace, thanksgiving) of the divinely created order. Moreover, from a traditional Christian perspective, all cultural production non-identically resonates with the Eucharistic sacrament, mysteriously re-presenting of the Logos in the midst and messes of finite existence, like war. The frontispiece and end-piece of In Parenthesis, both engravings by Jones, are moving examples of this attempted re-presentation. These allusive images convey the kenotic presence of Christ in instances of concrete, ineluctable suffering, and thus artistically “redeem the time” by recasting our vision of immense cultural-historical sacrifices like WWI.

Jones is not alone in making a profound contribution to renewing culture after the Great War: other giants include T. S. Eliot, J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and many, many, others. Yet it is through reading Jones’ writings that such an evening as this occurred to me. A related abiding irony is that, for many and perhaps most of us in this room tonight, war has only “occurred” to any of us in a mediated fashion, through the artifacts produced by those who lived it first-hand. Yet the circle goes both ways; soldiers on the battlefield have always also been influenced in their sense of what they were living through by engagement with things they have read or listened to or watched. Human experience is not a closed feedback loop, even if it seems nearly one at times. For the pen and the brush – the tools of art – are always sparring with the sword and the gun – the tools of war, even as the latter cleaves and redistributes the former’s fruits. War itself is an art, too. It requires the realization of an ideal for a specific telos. But the stakes of that art are high, for human blood is the ink and the paint on the page and canvas of its history.

Yet mankind is resilient. Looking both at the devastation of war and at the subsequent responses to it from poets and artists and thinkers suggests that the renewal of the Christian legacy of our civilization occurs in part through reflective engagement with the historical fact of warfare, spiritual and physical. While our Lord’s cryptic saying, “the Kingdom of heaven suffers violence; and the violent take it by force,” is likely meant to refer to the ascetic efforts of regular prayer and fasting, the history of the West, most of all in the modern era, is a history of physical as well as spiritual war. And in light of ongoing US engagement in armed conflicts across the globe, the question of the cultural and even spiritual significance of war is exigent for both the past and present.

I don’t have answers to these huge issues – but gathering together in order to be effected by them in some capacity seems an appropriate mode of commemoration. And that is one thing this evening is meant to be: an active instance of commemoration. The classical taxonomies of mental faculties are clear on this point: that the imagination depends on – and is sourced from – the memory. There is no thought that does not begin with remembrance.

Feast of St Menas of Egypt

Anno Domini 2017, November 11

Gaelan Gilbert is the Headmaster of Christ the Savior Academy in Wichita, KS. He is also the author of a collection of poems titled One Is Found First .

*This piece was presented at The Ladder, in Wichita, KS on the eve of Armistice / Veterans Day, Anno Domini 2019.

Contribute to Cultural Renewal by Sharing on Your Preferred Platform

In an isolating secularized culture where the Church's voice is muffled through her many divisions, Christians need all the help they can get to strengthen their faith in God and love toward their neighbor. Eighth Day Institute offers hope to all Christians through our adherence to the Nicene faith, our ecumenical dialogues of love and truth, and our many events and publications to strengthen faith, grow in wisdom, and foster Christian friendships of love. Will you join us in our efforts to renew soul & city? Donate today and join the community of Eighth Day Members who are working together to renew culture through faith & learning.