IN THE COLLECTED

Spiritual Homilies

of St. Marcarius the Great, we find one particular quote which distills in a few words the depth of Orthodox Christian anthropology. St. Macarius writes:

The Heart is but a small vessel, yet there are lions; there are poisonous beasts and all the treasure of evil. And there are rough, uneven roads; there are precipices. But there also is God, also the angels, the life and the kingdom, the light and the Apostles and the treasures of Grace—there are all things.

This Egyptian desert saint and founder of monasteries is not speaking metaphorically. He is articulating what the early Christians believed about: 1) the place of mankind in the universe; 2) the condition of men and women at the outset of their spiritual life; and 3) the location or focus of all Christian spiritual “work” done in concert with divine Grace. Our place? Man is a microcosmos, a little reflection of the entire universe, and its recapitulation. Our condition? We are the cross-roads for all the aspects of eternity and all the events of time, both the good and the evil. The focus of our spiritual work? The beginning and end of spiritual work is the Heart.

All the ordinances of the Orthodox Church, all her sacraments and dogmas, purpose to return men and women to the place of the heart, and from there lead them to the presence of Christ and the Kingdom of Heaven. From the Orthodox perspective, the great tragedy of modern people is not primarily immorality or unbelief—but rather that we fail to live from the center of our being where we have been made in the Image of God and where He speaks to us. We are divided and un-focused. We think, work, and even pray outside our heart.

Two questions naturally arise here. First, what is the heart? Obviously, “heart” is a technical term for Eastern Christians with a more nuanced and theological meaning than is usually ascribed to it in contemporary speech. The “Heart” or “Deep Heart” is the best translation of the Greek word nous

which is usually (and unfortunately) rendered “mind” in English bibles. But “mind” is too closely associated with thought, conjecture and reason—necessary human faculties, but not faculties at the center of our being. The nous

is the “intellect” of ancient philosophy—the means by which we have direct apprehension of Truth, and so it is the place where we meet God and speak with Him. The nous

is the “eye of the soul”—and ascetic practice in the Orthodox Church aims at clearing out and restoring this “eye” so that our spiritual sight will be clear. The nous

is the “deep heart” where my identity is most unique and the Image of God has been irremovably stamped on my being. It is also important to note that the heart is both a microcosmos

and a microecclesia—a holy temple—where it is possible for worship, prayer, and contemplation to continue without interruption, regardless of outward conditions. So the heart is at once the eye

the image

and the place of meeting.

There is a great Mystery in this. And what we could call a great “culture of the heart”—words and actions and music and doctrines and liturgy—has developed in the Orthodox Church solely for the purpose of helping men and women return to their heart and bidding them to take up the difficult life toward Christian perfection. To further illustrate this, the Greek word we usually translate “repentance” is metanoia, which means “change of heart.”

The first question “what is the heart” leads to the second, “how is this cleaning up, this changing, of the heart to be done?” Broadly, everything we think and do can either cleanse or obstruct the heart. The life of the body and the life of the mind are equally brought under scrutiny when one wishes to return to the center. Fasting, Prayer and Almsgiving, the classic Christian disciplines, begin and carry on the work of detaching us from our servile dependence on the material world, while Paul’s injunction “whatever is noble, beautiful or of good repute … think on these things” helps to re-orient the heart toward the source of Goodness, Nobility, and Beauty.

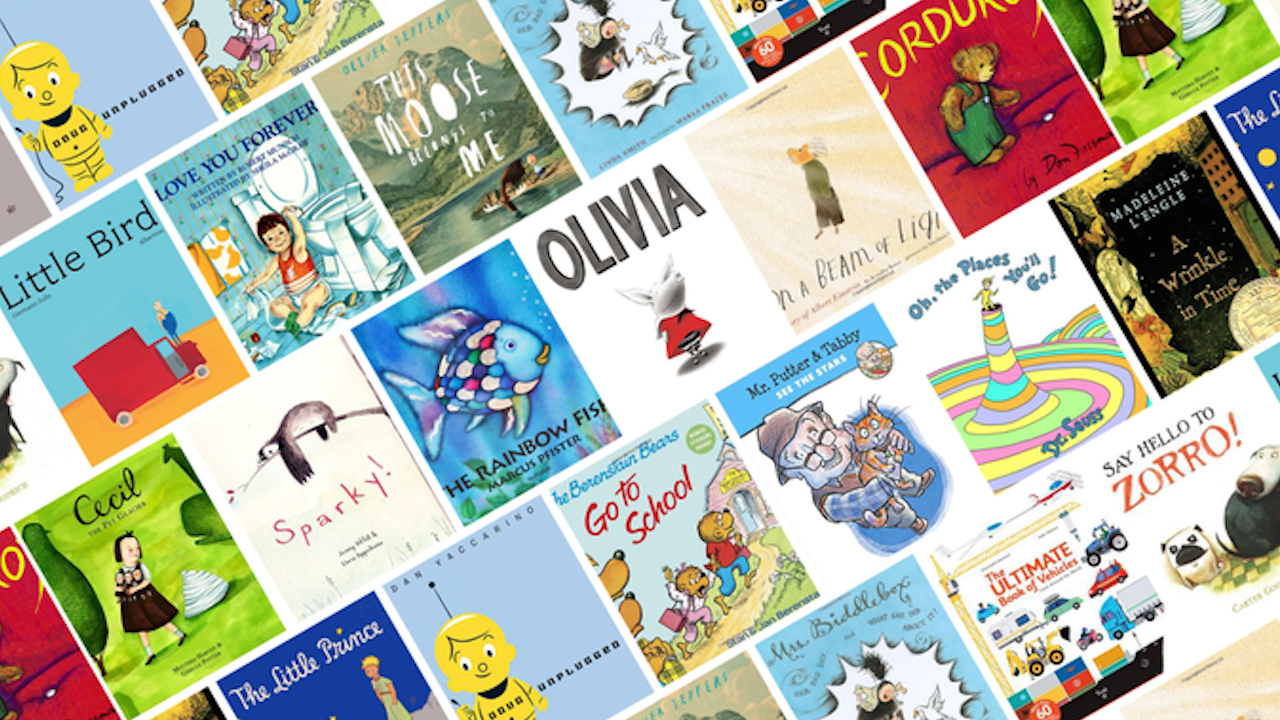

I believe, and my experience has demonstrated, that the best of fantasy literature—especially what is called “Children’s Classics”—is a most effective means of awakening the heart and leading us to it. In fact, what makes a literary work a classic, is precisely that its story, characters, and themes reveal in a figure something True about the “deep heart” and the nature of spiritual life. What Christian spirituality speaks of directly, the classics speak of as through the beauty of a prism. Spiritual guides will give you a trustworthy map—but the classics are like photographs of the place you long to reach.

IN ORDER TO

illustrate how fantasy literature can awaken the reader’s heart so that we may begin a journey to the presence of God, I have chosen four virtues which the Orthodox Fathers require for the cultivation of the heart and spiritual maturity. These four virtues are simple, yet are only attained through difficulty—and the soul can be prepared and encouraged to attain these virtues by exposure to classic tales. These 4 virtues are:

1. Testing—redemption through struggle

2. Fear of God—awe in the presence of the Holy

3. Faith—trust in God’s benevolence

4. Mindfulness of Death—remembering our mortality

Orthodox writers speak clearly about these and other virtues, not as something added to us for the sake of spiritual life but rather as a revelation of what is natural to us and from which we are unnaturally separated. So we begin with how I am made, then see how far we have fallen, and finally begin the process of return. I want to briefly look at examples of our four selected virtues in the writings of four classic stories.

1. Testing

All the great characters suffer. We suffer with them as their true selves are revealed, and their suffering instructs us in this most human art. Scripture says we must go through many trials, and the Orthodox Fathers teach us to expect temptations until our last breath. Inn J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Gandalf sits with Samwise and Frodo after Frodo’s recovery from a deadly knife-wound. Two pronouncements by Gandalf illustrate spiritual suffering.

“At the moment,” said Gandalf, “I will only say that I was held captive.”

“You?” cried Frodo.

“Yes I, Gandalf the Grey,” said the wizard solemnly. “There are many powers in the world, for good or for evil. Some are greater than I am. Against some I have not yet been measured. But my time is coming.”

Later in the same conversation, Gandalf is looking carefully at Frodo for any remaining symptoms of his ordeal with the Ringwraiths.

Gandalf moved his chair to the bedside, and took a good look at Frodo. The colour had come back to his face, and his eyes were clear and fully awake and aware. He was smiling and there seemed to be little wrong with him. But to the wizard’s eye there was a faint change, just a hint as it were of transparency about him. “Still, that must be expected,” said Gandalf to himself. “He is not half through yet, and to what he will come in the end not even Elrond can foretell. Not to evil, I think. He may become like a glass filled with clear light for eyes to see that can.

We are fully redeemed and revealed in testing, as these passages reflect so beautifully.

2. Fear of God

Fear of God, as awe and recognition of the presence of holiness, is fundamental to our nature as “doxological,” that is, worshipful beings. Orthodox Christians see themselves surrounded by a host of other persons—fellow humans and saints, ranks of angels, demons who have lost their personhood, and the Personal Trinitarian God. To some of these honor is due; to some veneration; to God, worship. In Kenneth Grahame’s Wind and the Willow, the Rat and the Mole have been out all night searching for Otter’s lost son, Portly. Just before dawn, weary with frustration, they begin to hear music as if Someone is guiding them toward an island further down stream. The music swells as they approach, and suddenly they find they are in the presence of the god of the animals who has helped them find the lost child.

Perhaps the mole would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling, he obeyed and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible color seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper … “Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking, “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of Him? O never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!

The author has captured in poetry the joy of obedience of the command to fear the Lord. It is clearer now why Solomon would say that “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” if the scriptural theophanies, like this one, are filled with such clarity of vision.

3. Faith

Faith is trust in God’s benevolent providence. Halfway through Pinocchio, the title character becomes, through his own poor choice, very ill and even close to death. His friend the Blue Fairy finds him on his sickbed. Pitying him, she mixes a potion that will make him well.

So she dissolved a certain fine powder in half a glass of water, and handing it to the puppet she said tenderly, “Drink it, and in a few days you will be better.”

Pinocchio looked at the glass, made a wry face and then asked in a whining voice, “Is it sweet or bitter?”

“It is bitter, but it will do you good.”

A constant theme in the Christian spiritual life is to believe, to trust, that the chaotic and unpredictable are still ruled by Providence. In fact, anyone who can learn that sometimes “it is bitter but it will do you good” will find the undulations of life much easier to bear.

4. Mindfulness of Death

We are mortal creatures. As such, we should always remember our weakness and the temporal limit of our lives. Throughout The Magician’s Nephew

by C. S. Lewis, one principle character, Digory, is constantly returning to the thought of his mother’s illness. She is not expected to recover, and Digory feels the hopelessness and powerlessness of someone for whom all meaning has been drained out of life. This feeling becomes at various times sadness—as at his first meeting with Polly; anger—as toward Uncle Andrew’s callousness; and finally stern resolve—as when a possible cure for his mother is found in the silver apples, but he must wait to ask permission for them so that the cure can be given lawfully.

“But please, please can’t you give me something that will cure Mother?”

Up till then, Digory had been looking at the Lion’s great front feet and the huge claws on them; now, in despair, he looked up at its face. What he saw surprised him as much as anything in his whole life. For the tawny face was bent down near his own, and (wonder of wonders) great shining tears stood in the Lion’s eyes.

“My son, my son,” said Aslan, “I know. Grief is great. Only you and I in this land know that yet.”

Those who keep the end always in mind will learn to ask for the right gifts and to pray with the proper humility, and will learn that God understands our mortality and has made even death part of His plan for eternal life.

OF COURSE, I could go on and on about the preparation of the heart through stories. I could speak of spiritual wholeness in the conversations between Dumbledore and Harry Potter (J. K. Rowling). I could mention the perseverance of the toy mice in The Mouse and His Child

(Russell Hoban), or the amazing discernment shown by The Little Prince

(Antoine de Saint-Exupéry). I could learn not to judge my neighbor through great complicated characters like John Silver in Treasure Island

(Robert Louis Stevenson).

But I would like to finish with a thought about what we call the “real world” or “daily life.” Very little is left in our culture to cultivate the deep heart and prepare it for spiritual life. We have all—even Christians—forgotten our calling to become, to grow, and to mature. We live outside our hearts, and so cannot act in simplicity according to our nature in the image of God. Our Cartesian epistemology demands that we see the mundane as terminal while true spirituality and its translation into literature whispers that the mundane is the edge of glory. Here are three final stories to illustrate. Let us say the first is Real. The second illustrates the Real. The third denies reality.

An Orthodox monk goes into his monastic cell. And when asked, “why are you sitting here, not doing anything productive?” He replies, “I am not sitting, I am on a great journey.”

A little girl climbs into a wardrobe during a game of hide-and-seek. She suddenly finds that she has discovered a whole, strange county of ice and snow that must soon be brought to war and set free.

A man, Rene Descartes, shuts himself in an oven for a day and is there “alone,” with nothing but his thoughts. He emerges and begins to articulate a new philosophy: “I think, therefore I am.”

The first two stories are remarkably consonant. The monk has entered his deep heart, and there encounters God and neighbor, experiencing in reality the image of Lucy entering the small space of a wardrobe and discovering there an unknown world. Both find the inside larger than the outside, and emerge from their encounter more than they were at the start.

But the third story, the tale of Descartes’ oven? History tells us this story is “true.” But the oven was not, for Descartes, an entrance to anything greater than himself. In fact, he emerged proclaiming that only a small part of himself was “real,” denying the fullness of his humanity as known in the heart. Our culture has suffered the loss of its Heart ever since.

*An earlier version of this was originally delivered as a lecture for the 2009 Literary Festival at Newman University in Wichita, Kansas. This version was published in Eighth Day Institute's inaugural 2012 publication, The Book, pp. 113-120.