EVERY BAPTIZED

Christian is obliged to his baptismal promises to renounce sin and to give himself completely, without compromise, to Christ, in order that he may fulfill his vocation, save his soul, enter into the mystery of God, and there find himself perfectly “in the light of Christ.” […]

Every Christian is therefore called to sanctity and union with Christ, by keeping the commandments of God. Some, however, with special vocations have contracted a more solemn obligation by religious vows, and have bound themselves to take the basic Christian vocation to holiness especially seriously. They have promised to make use of certain definite and more efficacious means to “be perfect” – the evangelical counsels. They oblige themselves to be poor, chaste, and obedient, thereby renouncing their own wills, denying themselves, and liberating themselves from mundane attachments in order to give themselves even more perfectly to Christ. For them, sanctity is not simply something that is sought as an ultimate end: sanctity is their “profession” – they have no other job in life than to be saints, and everything is subordinated to this end, which is primary and immediate for them.

Nevertheless, the fact that religious and clerics have a professional obligation to strive for holiness must be properly understood. It does not imply that they alone are fully Christians, as if the laity were in some sense less truly Christian and less fully members of Christ than they. St. John Chrysostom who, in his youth, came close to believing that one could not be saved unless he fled to the desert, recognized in later life, as bishop of Antioch and then of Constantinople, that all the members of Christ are called to holiness by the very fact that they are His members. There is only one morality, one holiness for the Christian – that proposed to all in the Gospels. The lay state is necessarily good and holy, since the New Testament leaves us free to choose it. Nor is the lay state one in which it is sufficient to maintain a kind of static and minimal holiness, simply by “avoiding sin.” […]

St. John Chrysostom points out that the mere fact that the life of the monk is more austere and more difficult should not make us think that Christian holiness is principally a matter of difficulty. This would lead to the false conclusion that because salvation seems less arduous for the layman it is also in some strange way less truly salvation. On the contrary, says Chrysostom, “God has not treated us [laypeople and secular clergy] with such severity as to demand of us monastic austerities as a matter of duty. He has left to all a free choice [in the matter of His counsels]. One must be chaste in marriage, one must be temperate in meals … You are not ordered to renounce your possessions. God only commands you not to steal, and to share your property with those who lack what they need” (Commentary on 1 Corinthians, ix, 2).

In other words, the ordinary temperance, justice, and charity which every Christian must practice, are sanctifying in the same way as the virginity and poverty of the nun. It is true that the life of the consecrated religious has a greater dignity and a greater intrinsic perfection. The religious takes on a more radical and more total commitment to love God and his fellow man. But this must not be understood to mean that the life of the layperson is downgraded to the point of insignificance. On the contrary, we must come to recognize that the married state is also most sanctifying by its very nature, and it may, accidentally, imply sacrifices and a self-forgetfulness that, in particular cases, would be even more effective than the sacrifices of religious life. He who in actual fact loves more perfectly will be closer to God, whether or not he happens to be a layman.

Hence St. Chrysostom again protests against the error that monks alone need to strive for perfection, while lay people need only avoid hell. On the contrary, both lay people and monks have to lead a very positive and constructive Christian life of virtue. It is not sufficient for the tree to remain alive, it must also bear fruit. “It is not enough to leave Egypt,” he says, “one must also travel to the promised Land” (Homily xvi on Ephesians). […] The monks have their important part to play in the Church. Their prayers and sanctity are of irreplaceable value to the whole Church. Their example teaches the layman to live also as a “stranger and pilgrim on this earth,” detached from material things, and preserving his Christian freedom in the midst of the vain agitation of the cities, because he seeks in all things only to please Christ and to serve Him in his fellow man.

In short, according to Chrysostom, “The beatitudes pronounced by Christ cannot possibly be reserved for the use of monks alone, for that would be the ruin of the universe.”

But in fact, all of us who have been baptized in Christ and have “put on Christ” as a new identity, are bound to be holy as He is holy. We are bound to live worthy lives, and our actions should bear witness to our union with Him. He should manifest His presence in us and through us. Though the reminder may make us blush, we have to recognize that these solemn words of Christ are addressed to us: "You are the light of the world. A city set on a mountain cannot be hidden. Neither do men light a lamp and put it under a measure, but upon the lampstand, so as to give light to all in the house. Even so let your light shine before men, in order that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven" (Mt. 5:14-16). […]

We are supposed to be the light of the world. We are supposed to be a light to ourselves and to others. That may well be what accounts for the fact that the world is in darkness! What then is meant by the light of Christ in our lives? What is “holiness”? What is divine sonship? Are we really seriously supposed to be saints? Can a man even desire such a thing without making a complete fool of himself in the eyes of everyone else? Is it not presumptuous? Is such a thing even possible at all? To tell the truth, many lay people and even a good many religious do not believe, in practice, that sanctity is possible for them. Is this just plain common sense? Is it perhaps humility? Or is it defection, defeatism, and despair?

If we are called by God to holiness of life, and if holiness is beyond our natural power to achieve (which it certainly is) then it follows that God Himself must give us the light, the strength, and the courage to fulfill the task He requires of us. He will certainly give us the grace we need. If we do not become saints it is because we do not avail ourselves of His gift.

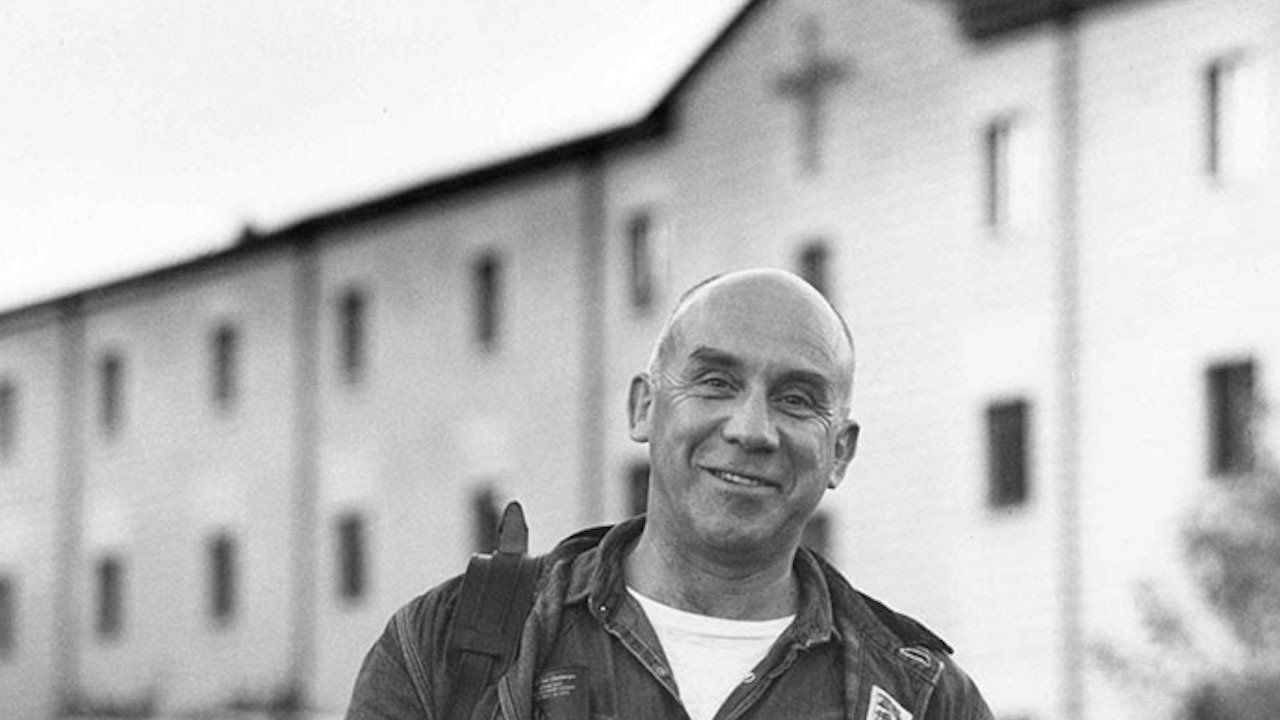

~Thomas Merton, Life and Holiness

*Register for the Eighth Day Symposium

("For I Am Holy: The Command to Be Like God") before regular registration rates begin on January 7.