N. T. Wright’s appreciative review of Mere Christianity

(“Simply Lewis”) offers at least three critiques: the “astonishing absence of the Resurrection,” its problematic “argument for Jesus’ divinity,” and “the complete absence of anything to do with Jesus’ announcement of God’s kingdom.” I find Wright’s critiques compelling. But there is another line of critique that needs to be pursued.

Timothy George’s piece on “A Thicker Kind of Mere” paves the way. But it does not go far enough. George makes an important clarification of how Lewis used the word mere: it “is a thicker kind of mere—not mere as minimal but mere as central, essential.” I agree. But what is the essential? And, more specifically, is Lewis’ “mere Christianity” thick enough?

In his preface to Mere Christianity, Lewis explains his motivation for writing the book. According to Lewis, he wrote it for his unbelieving neighbors, “to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times.” Lewis here sounds like the Church Fathers. Two examples will suffice:

In the Catholic Church itself we take the greatest care to hold that which has been believed everywhere, always and by all. That is truly and properly “Catholic,” as is shown by the very force and meaning of the word, which comprehends everything almost universally. We shall hold to this rule if we follow universality, antiquity, and consent. We shall follow universality if we acknowledge that one Faith to be true which the whole Church throughout the world confesses; antiquity if we in no wise depart from those interpretations which it is clear that our ancestors and fathers proclaimed; consent, if in antiquity itself we keep following the definitions and opinions of all, or certainly nearly all, bishops and doctors alike. —St Vincent of Lerins, Commonitory 2.6

Having received this preaching and this faith, the Church, although scattered in the whole world, carefully preserves it, as if living in one house. She believes these things everywhere alike, as if she had but one heart and one soul, and preaches them harmoniously, teaches them, and hands them down, as if she had but one mouth. —St Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.10.2

Later in Lewis’ preface, he notes that the greatest area of dispute among Christians is the importance of their disagreements, i.e., what is absolutely essential. If you follow St Irenaeus and St Vincent, as I do, the test is universality, antiquity, and consent.

So what’s wrong with the “mere Christianity” offered by Lewis? It does not include certain elements that have been believed everywhere, always, and by all. In other words, it is too thin. It needs to be thickened. (To see what I mean by a thickened mere Christianity, read my explanation of

Eighth Day Ecumenism.)

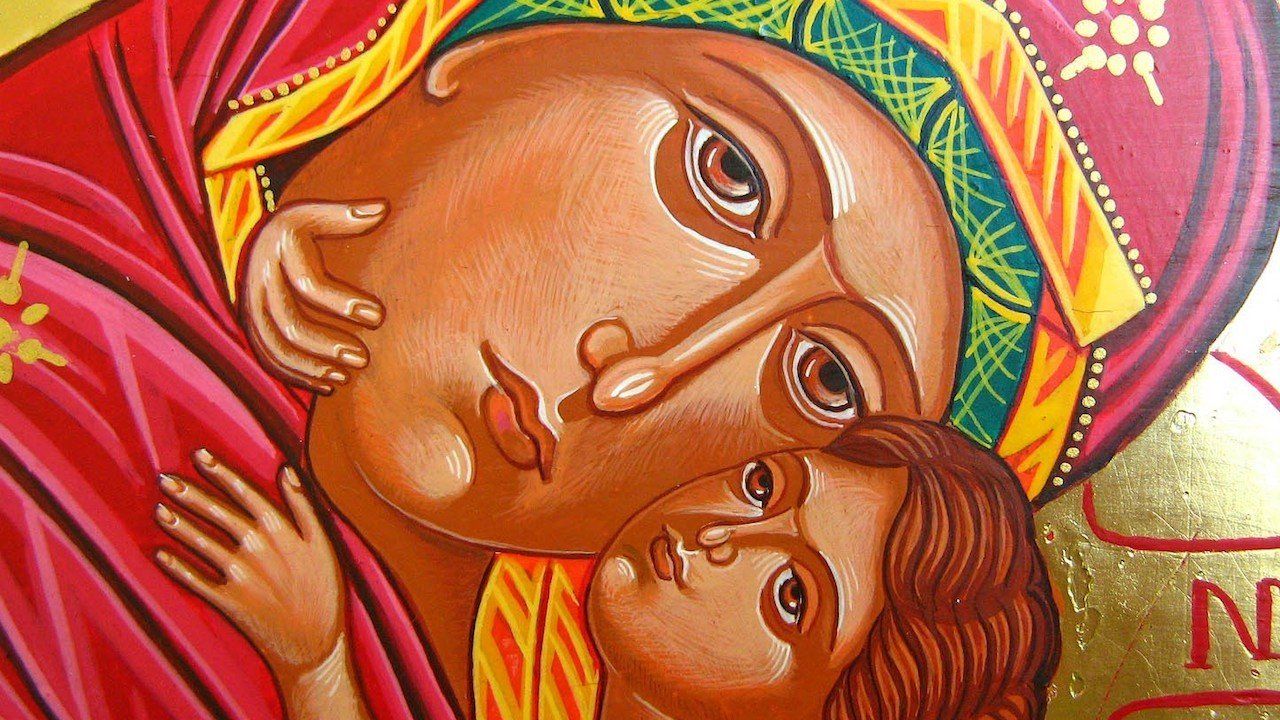

Let me here offer one concrete example of how Lewis’ mere Christianity is too thin. Returning to the preface of Mere Christianity, Lewis laments people drawing unwarranted conclusions about the fact that he never says anything about the Virgin Mary beyond asserting the virgin birth of Christ. He goes on to defend his silence: “To say more would take me at once into highly controversial regions. . . . If any topic could be relied upon to wreck a book about ‘mere’ Christianity—if any topic makes utterly unprofitable reading for those who do not yet believe that the Virgin’s son is God—surely this is it.” The problem is that the ancient, universal consensus of the Church disagrees. And so do I.

In order to understand who the Virgin’s Son is, one must consider His mother. According to Fr. Georges Florovsky, “The Christological doctrine can never be accurately and adequately stated unless a very definite teaching about the Mother of Christ has been included. . . . to ignore the Mother means to misinterpret the Son.” (For a lengthier except of this Florovsky quote, see The Patristic Word on June 20.) We see this played out in the Christological controversies that were settled in the seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787 A.D.). The first and second Ecumenical Councils (325 and 381 A.D.) declared our Lord Jesus Christ to be “incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary.” The third Ecumenical Council (432 A.D.) declared Mary to be Theotokos, the Mother of God. And the fifth Ecumenical Council (553 A.D.) formally endorsed the term “Ever-Virgin.”

The Ever-Virgin Theotokos is central and essential to a thick mere Christianity. Even if discussing Mary takes us “into highly controversial regions” or “wreck[s] a book”—or a blog post!—she must be included in the thick kind of mere Christianity Eighth Day Institute advocates. Eighth Day Institute loves C. S. Lewis. But we think his mere Christianity needs to be thicker.

Erin Doom

is the founder and director of Eighth Day Institute. He lives in Wichita, KS with his wife Christiane and their four children, Caleb Michael, Hannah Elizabeth, Elijah Blaise, and Esther Ruth.