THIS ADMIRABLE

little book, first published in 1931 in a limited edition, is important less for its erudition about the theory and practice of typography than for the moral support it gives to artists, whose principal concern is the quality of their work; to businessmen, who are chiefly interested in the bottom line; and to printers and publishers, who are more concerned with traditional practices than with wild ideas.

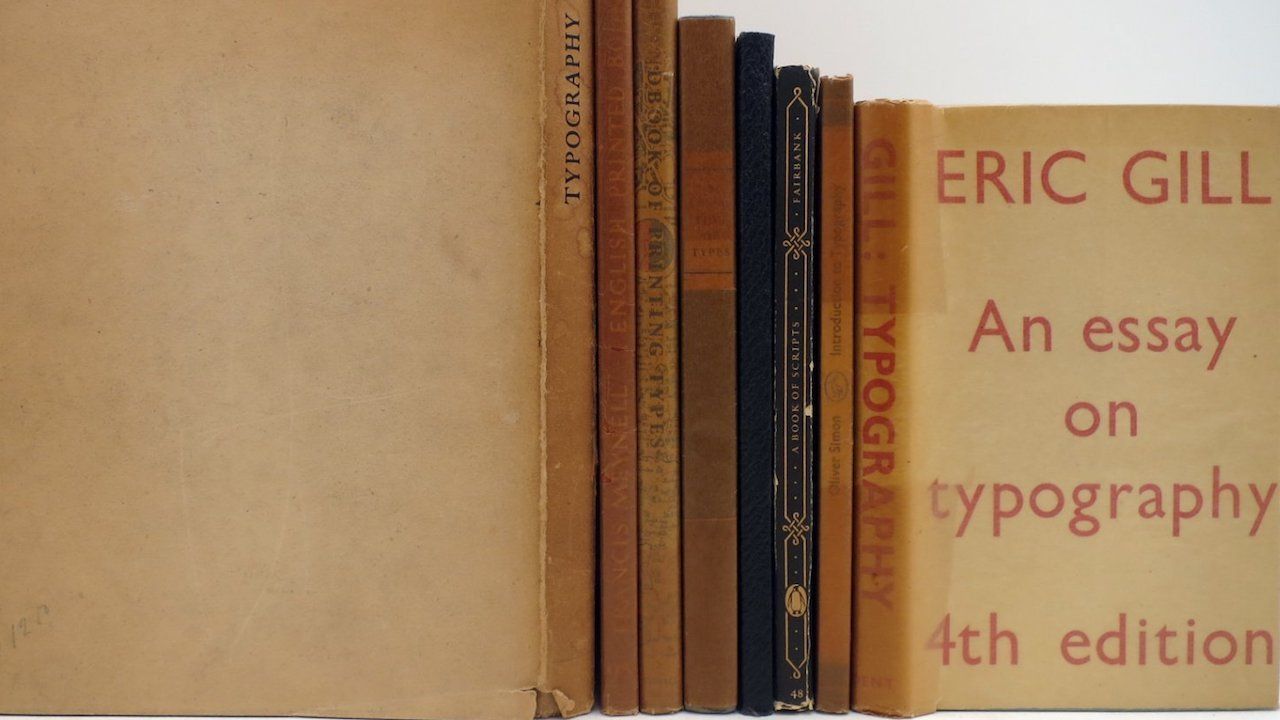

Even though An Essay on Typography

deals with technical difficulties, the history and evolution of letters, the craft of typography, type design and manufacturing, page makeup, color and ink preparation, paper making, book binding, publishing and even orthography, it is written with clarity, humility and a touch of humor. Eric Gill’s writing style moves between a chuckle and a grimace, avoiding a lot of technical jargon and pretentious allusions. And Gill, who was not only a British typographer, but a sculptor, engraver and writer, panders to no one. One wonders how so much could have been packed into such a tiny package - probably enough to have made experts in typography and printing like the Americans Daniel Berkeley Updike and Theodore L. De Vinne marvel.

Gill’s ultimate goal, like that of any serious artist, had less to do with means than with ends - the proper balance between form and content, between man and machine. He cautions the worker not to get too involved with the machine. “It is important that the workman should not have to watch his instrument, that his whole attention should be given to work.” “The mind,” he further asserts, “is the arbiter of letter forms, not the tool or the material.” For those dazzled by the computer, who see the machine as a magic muse, these words are particularly useful.

On more than one occasion he implies that the businessman’s involvement in esthetics is incidental, not intentional. “And the printer whose concern is quality,” he says, “is not a man of business.” Similar expressions – “by men of brains rather than by men of business” and “the history of printing has been the history of commercial exploitation” - sum up Gill’s attitude about industry, even though he owed much of his livelihood to English type founders.

He even advises the publisher where his name should appear in a book, and calls the ordinary title page “a showing off ground . . . an advertisement for the printer and publisher.” The names of printer and publisher, he says, should appear at the end of the book where they logically belong. The design of the title page of the 1931 edition, for example, is a masterpiece of understatement, containing the title, the author’s name and the table of contents in a design so splendid that, even today, it would be considered revolutionary.

[…]

To Gill’s eye, lettering was “as beautiful a thing to see as any sculpture or painted picture.” Yet the relationship between words and spelling, between printed words and speech, he considered irrational, and he suggested that some sort of shorthand system, which he called phonography, be provided as a possible solution. “We need a system in which there is real correspondence between speech . . . the sounds of language and the means of communication.” This had nothing to do with speed. “Think slowly, speak slowly, write slowly” is what he exhorted his readers. […]